JOURNAL ARCHIVE

| Many of those entering the big orange doors of the Dastkar shop in Hauz Khas Village, in search of a hand-crafted gift or embroidered kurta, are quite unaware that anything except lower prices and the absence of air-conditioning mark it out as different from the other 70-odd shops and boutiques that surround it. Others, activists and NGOs, question why Dastkar, a registered voluntary society and development organisation, has anything to do with a "commercial" activity like marketing. For Dastkar, however, the Dastkar exhibitions and Bazaars and our shop - run on a non-profit basis, with craftspeople owning the merchandise, and donating 20% of their monthly sales to the running costs - are a linked and essential part of the support services we give to craft producer groups all over the country and. Helping craftspeople learn to use their own inherent skills as a means of employment generation and self-sufficiency is the crux of the DASTKAR programme. Giving them a market to do so is the culmination of as well as the catalyst for the varied DASTKAR projects, training programmes, product development inputs and loan capital assistance to our family of craftspeople. The Dastkar shop and the Dastkari Bazaars are where we test-market not just the potential of Dastkar-developed products, but the efficacy of Dastkar-developed solutions to the problems of the craft sector in the current economic climate. Is craft commercially viable today; or is it just a subsidized development sector cop out? Much depends on the intervening agency or NGO. The means to earn and be independent is the carrot that can lead rural craftspeople into the development process. Similarly, an attractive cost-effective product is the carrot that can tempt the urban consumer into contributing towards that development. Guiding the process - from identifying the skill and creating awareness of it's potential in both craftsperson and consumer; developing, designing, costing and then marketing the product, and finally (but as importantly) suggesting the proper usages and investment of the income generated, - is the role of the NGO or development agency. And there's the rub..... A cause, however meritorious, or a slogan, however emotive and catchy, does not sell a product. The consumer does not buy out of compassion. The end must be competitive - not just in its worthiness of purpose, or the neediness of its producer - but in cost, utility and aesthetic. The handicrafts sector is always thought of as a very comfortable place to create more income and employment, especially for women. It is a home-based industry which requires a minimum of expenditure, infrastructure or training to set up. It uses existing skills and locally available materials. Inputs required can be easily provided and these are more in terms of product adaptation than expensive investment in energy, machinery or technology. Also, income generation through craft does not (and this is important in a rural society) disturb the cultural and social balance of either the home or the community. The energy of a new source of employment and income can have a catalytic effect in revitalising communities that were as denuded and deprived as the arid, devastated landscapes around them - Urmul, SEWA Lucknow, Banascraft, Ranthambhore, Sandur Kushal Kendra, are just some of the examples Dastkar has been personally involved in. SEWA Lucknow started in 1984 with 12 women, a tin trunk and 10,000 rupees. Today there are 3,800 women and an annual turnover of over two hundred million rupees! But there are dangers. Success stories are to be learnt from, not blindly followed. The craft sector is already a very crowded place and the existing market inadequate for the number of producers trying to squeeze into it. We should think carefully before creating more. Strategies, however successful, should not become static. In the Dastkar Ranthambhore Project, (started 4 years ago to provide work to women in re-settled villages displaced by the Ranthambhore Tiger Park) the 100-odd women today sell about eight lakhs of goods a year through DASTKAR. But, as numbers and production capacities increase, they have to think of markets and products with an outreach beyond Hauz Khas Village and urban bazaars. The next step is their own shop in Ranthambhore, selling products developed for village consumers as well as tourists visiting the park. Similarly, SEWA Lucknow gradually built up its production capacity, brand name and turnover for the first ten years, selling one-of-a-kind kurtas and saris, exclusively through it's own periodic exhibitions and sales. Today - with sales at each five day exhibition an unmanageable 7-8 million rupees - it needs to, and is in a position to, branch out into wholesale and export orders; and is exploring the possibilities of an all-India infrastructure of franchise marketing. All too often when we think of employment generation for women; we think of that employment as a kind of handout or hobby. We should be very, very sure that that employment, and the payment for that employment, is not just a subsidized placebo, but an integrated part of a long-term economic strategy. An NGO or women's group however, often comes together with different priorities and objectives - health, social awareness, environmental issues or education. The income generation component of their project is tacked on later, when they discover that without an immediate economic solution it is difficult to make an entry into the target community, or win their confidence. It is then tackled in an off-the-cuff, short-term way by people who, whether they are grass roots activists, Gandhians or missionary Fathers are obviously not professionals in merchandising and marketing! All too often, making money (let alone a profit!) is dismissed as the least worthwhile and meaningful component of the project - a rather degrading activity for a social welfare organisation. I agree that income generation, by itself, should not be considered a synonym for development. It cannot - and should not - be. It is, however, if used skillfully, the entry point for many other aspects of the development process - education, health and family planning, social awareness, women's upliftment. The primary aspiration, the first request, of human beings everywhere is economic freedom - from husbands and fathers, from exploitative landlords, from money lenders or middlemen, or whatever. Therefore it is frightening that this crucial aspect, on which the livelihoods and future of lakhs of men and women depends, is undertaken in so casual a manner. So often the key decisions of identifying the product and it's potential market are taken quite at random. There is no market survey, no checking of locally available raw material or un-tapped traditional skills, no costing, no identification of potential buyers or marketing chains. There are no production plans or financial forecasts. Endless schemes for tailoring units, patchwork, knitting, weaving are initiated. Unemployed craftspeople become Trainers and, in turn, train more unemployable people to make more unsellable products. Endless cross-stitch 'Duchess sets' and crochet table covers proliferate, regardless of a glut in the market of thousands of similar, useless, badly put together and over-priced products. Subsidized discount sales, stipends and grants disguise the economic unviability of the stock-piles of unsold goods. The inherent skills, strengths and motifs that exist in every traditional community are not even studied or understood. Nowhere in the commercial sector would the development and sale of thousands of lakhs of rupees of products (let alone the livelihoods of thousands of people) be left to part-time amateurs (however well meaning) with no experience or training in economics, product design or merchandising. But in the craft and development sector, a bureaucrat (who has come from the Waterworks Department and will be in Family Planning next year!) can become a arbiter of what a export line of soft furnishings should look like; or a nun be forced into making decisions on employment strategies for empowering thousands of tribal weavers. Obviously they have no alternative except to plunge in and follow their instinct. The imperative to do something and to do it soon, is just too strong. The field organisation does not know whom to contact, and the institutions that are supposed to help, whether NID, the Export Promotion Council, State Development Corporations or the IITs and Marketing and Management Institutes, are often very remote - both geographically and in their understanding of the problem. So, more carpet training centres start in non-wool producing areas at a time when the traditional carpet industry is already in recession; Tribals are encouraged to laboriously embroider satin-stitch tea cosies with Little Bo Peep on them (regardless of the fact that the intended consumer increasingly drinks his tea 'ready made' in a mug!); Meanwhile industrialised units in Trans-Jumna replicate tribal jewelry in white metal to meet the export and retail demand of frustrated buyers unable to buy the traditional product in its traditional place. Kantha embroiderers are given designs out of WOMAN & HOME; a well-meaning Managing Director of Orissa Handicrafts sets up a Training Scheme to teach Kantilo bell-metal craftspeople to copy Moradabad Brass; a highly skilled craftsman is brought to the level of an unskilled one by a well meant but pernicious daily wage scheme. There are hundreds of similar, unthought through, emotively conceptualised but potentially damaging initiatives all over India today. Like any other entrepreneur, the NGO should explore the gaps in the market before production, rather than saying, "Well, I've got this product, let's see where I can shove it in". This is ridiculous and self-destructive. Nor should one say, "X did this and it was very effective so lets duplicate it on an all-India basis". The success of the SEWA Lucknow experiment had people approaching DASTKAR to start chikan embroidery training units in places as far-flung as Madhya Pradesh and Bangladesh - each of which has its own unique heritage of much more appropriate local skills! The Sandur Manganese Company ran a Welfare Project for Lambani women at a loss for twenty years, before Dastkar suggested that the rich, inherent embroidery skills of the women could create much more marketable products than the machine tailored, badly constructed pink plastic bags and bibs they had been trained to make. The Lambani women went on to sell 3 lakhs at their first solo exhibition and now have export orders from all over the world. Simply getting the product right is not enough either, without the right market outlets to match. NABARD recently approached DASTKAR to replicate its Ranthambhore project in villages throughout the area; several hundred had been sanctioned by the State Government towards rural development in the district. But when they were told that the creation of craft production units on such a scale would mean investment in a matching all-India network of marketing outlets and advertising, they disappeared, never to be heard of again....! Amul Dairy is the rural development success story. It gives employment to 16 lakh people. But it would not be able to do so without an appropriate distribution system; however good the milk, butter and cheese. India is unique in still being able to produce a hand-crafted product at a price that matches, or is even cheaper than, it's factory-made mass-produced counterpart. But public awareness of the cost-effectiveness, functionality and range of craft products is limited by their being sold only in exclusively "crafty" outlets. Hand-crafted leather juthis and bags should be sold with other leather products; hand-crafted baskets, bed linen, durries and planters be available in neighbourhood household emporiums; hand-crafted furniture in furniture shops rather than once a year at the Surajkund Mela. A mind-set that restricts anything hand-crafted to a line of Government Emporia on Baba Kharak Singh Marg, the Crafts Museum and an occasional Bazaar, will only succeed in the increasing marginalisation of crafts and their producers. So will the idea that craft should be purely decorative bric-a-brac, and that tourists and the urban elite are its only target customers. The current much coined terms "exclusive" and "ethnic" are singularly limiting and inappropriate when marketing skills and products with a potential producer base of 23 million! Those of us working in the craft sector are often accused of concentrating on the aesthetic rather than the economic; the cream rather than the bread and butter. Crafts in India have many applications, and an incredible potential. We should neither neglect the simple utilitarian crafts, or down-grade those that are art forms. It is sad to see the functional basketry and matting of the North East gradually being squeezed out of their State Emporia because they occupy more shelf space and are less value-per-unit than costume jewelry and garments. It is equally sad to see the living skills that made the Taj Mahal reduced to making pillboxes. Serving tea in bio-degradable terra-cotta khullars on Indian Railways is often used as a paradigm for the practical, rather than esoteric, usage of craft. I agree, and far prefer the taste of earth to plastic. However, a khullar is the simplest item in the Indian potter's repertoire. He is capable of making many other creative, useful and value-added products. I think the recent addition of planters, jars, lamp and table bases an equally exciting example of matching traditional producer skills to changing consumer needs. It has added a new energy to road-side potters colonies all over India, that might otherwise have died when the frigidaire replaced the surahi in the urban Indian home. Every area, every community has a different tradition, a different need, a different capacity. Production and marketing plans should be based on these. Ideally an NGO should link the craft community to a consumer community which is close by; using locally accessible materials to make products in local demand. That way, both NGO and craftsperson are in control of the dynamics of production and market, supply and demand. One of the most satisfying Dastkar projects was where a group of women weavers from Tezpur approached Dastkar for help to enter the urban Delhi market. Dastkar product development, design and organisational inputs helped create a product that now sells so well in the local Assam market that they do not need the Dastkar Bazaars and Delhi market at all! All the more disappointing therefore, that so many activist groups and NGOs opt for the urban retail market of exhibitions, sales and Melas, instead of the rural and institutional marketing that would be so much more appropriate to their areas of expertise and experience. Free too, from the moral dilemmas of a Gandhian organisation making and trying to flog high-price, high-fashion garments; or radicals agonising over whether to advertise in the Hindustan Times! In recent times, the survival of many drought or disaster-prone areas of rural India has depended on craftspeople re-discovering the skill and potential of their hands. As Ramba ben, a craftswoman from a Dastkar project in Banaskantha told me, "The lives of my family now hang from the thread I embroider". So, I do think income generation through the marketing of craft is something that can work - both commercially and as a catalyst for change and development. But it will only work if we think it through very carefully - with our heads as well as our hearts; with reason as well as caring. First published in the CAPART magazine 'Moving Technology'. |

| Background In 2006, the All India Artisans and Craftworker’s Welfare Association (AIACA), based in New Delhi, and the international NGO, Aid to Artisans (ATA), began a three year public-private partnership to implement the Artisan Enterprise Development Alliance Program (AEDAP) in India. Most handicrafts created by Indian artisans are made with the intention of being sold commercially, yet many remain unable to reach the market. The aim of AEDAP was therefore to support Indian artisan enterprises to become more competitive in the market. The objective of the program was to leverage skills and expertise; to bring human, material and financial resources to bear on addressing various challenges throughout the supply chain related to Indian craft production and marketing. |

| The Design Intervention The term ‘design intervention’ has been widely adopted to describe the process of linking designers to craft enterprises. The concept is that the designer will bring a new approach, or a different way of seeing artisanal skills and expertise, and share their design capabilities and understanding of global market demands. The designer does not impose but rather ‘unlocks’ the potential of the existing skill by tweaking it to make it more saleable to consumers and in so doing may transform a craft that is struggling to find a market. Here, the designer operates at the intersection between the commercial economy and artisan, serving as the bridge between maker and market. |

|

Implementation AIACA and ATA selected and paired a designer with a craft group. The designer then spent time on-site for a period of up to two weeks with the craft enterprise. The designer was required to assess the situation, then work to find design solutions to the obstacles the craft groups were encountering in reaching the market. In the first two years, the designer was a US-based consultant who worked on site with the craft enterprise. In the third and final year a local Indian designer was located on site with the AEDAP partner. The designer was provided with mentoring support from designer-mentors in the US, who provided inputs and advice on colour and product range. A total of 17 groups participated in the AEDAP design intervention. |

| The Craft Enterprise DR is based in the Sawai Madhopor district of South-East Rajasthan; they are located adjacent to one of the world’s most famous natural tiger reserves. Many local people were removed from their traditional lands in the creation of the Tiger Reserve and re-settled in areas just outside the Park. As a result, they lost their access to wood, water and farming lands. In order to support these villagers to rebuild their social and economic life, Ranthambore Foundation was created to work with the displaced population to work on rebuilding the displaced communities’ social and economic foundations through various income generation programs.In 1989 the Delhi- based craft NGO, Dastkar, took charge of the income generation programme for the village craft people. The target group were not professional artisans. Instead, craft skills were being practised in an unstructured, undeveloped way, mainly as a means of reusing and recycling waste materials such as rags, or newspapers to create items of daily use.Dastkar began its work training local people, building on these craft skills to create livelihoods. The enterprise now works with approximately four hundred women artisans. They have constructed a craft centre, which also doubles as a retail space and functions as an informal gathering place for the community, where the women can gossip, sing, and work together. DR provides life insurance, health insurance, a provident fund, and a micro-credit system for the women artisans and their families. |

Market Opportunities

DR has a sales and retail centre from which to sell its products, with ample space to display all their products. This retail store is a significant advantage for DR, as it is adjacent to the Tiger Reserve which is a thriving tourism hub. DR is situated in an ideal location near the major hotels and at least two tour buses visit the group every week. A range of hotels, from government run budget accommodation to exclusive five star resorts, offered sales opportunities for DR via their retail outlets. Whilst the AEDAP had been structured to support Indian artisans to connect to global markets, Griffith’s analysis of the tourism industry identified that the most viable business proposition was investing in local sales. At the time, the US market was glutted and mature; in contrast, the domestic Indian market was strong, and rapidly growing. A focus on the immediate market also meant that DR reduced its dependence on sales from external factors in the export market, such as volatile, seasonal fashion trends. They also reduced costs related to transportation. Therefore, the strategy was to create products that could tap into the sales potential of the tourism industry.

Market Opportunities

DR has a sales and retail centre from which to sell its products, with ample space to display all their products. This retail store is a significant advantage for DR, as it is adjacent to the Tiger Reserve which is a thriving tourism hub. DR is situated in an ideal location near the major hotels and at least two tour buses visit the group every week. A range of hotels, from government run budget accommodation to exclusive five star resorts, offered sales opportunities for DR via their retail outlets. Whilst the AEDAP had been structured to support Indian artisans to connect to global markets, Griffith’s analysis of the tourism industry identified that the most viable business proposition was investing in local sales. At the time, the US market was glutted and mature; in contrast, the domestic Indian market was strong, and rapidly growing. A focus on the immediate market also meant that DR reduced its dependence on sales from external factors in the export market, such as volatile, seasonal fashion trends. They also reduced costs related to transportation. Therefore, the strategy was to create products that could tap into the sales potential of the tourism industry.

Design Objectives

Based on consultation with DR, along with an assessment by AIACA and ATA, the designer was given the following objectives:

|

| Design Inputs DR’s main product line was hand block printed products. Griffith saw this market as saturated and flooded, with both conventional and contemporary products. To give the products a competitive edge, new applications and new ways of interpreting the block prints needed to be developed. However, there were limitations; for instance, whilst DR craft workers were adept in sewing, finishing, stitching, and the construction of simple products, due to some restrictions in terms of access to raw materials and pattern making skills, most products had to remain unstructured. A solution to the limitations was to introduce colour as a main focal point that could give DR a competitive advantage in the market. Therefore, Griffith introduced vibrant colours in blue, pink, orange, and green; these made the products ‘pop’ and became an important element in the collection. |  |

Griffith also developed more comprehensive product lines that could be put together into collections according to colour, style, and print. Griffith and DR also recognized the importance of including the iconic Tiger motif on products. The Tiger was DR’s Unique Selling Proposition (USP); it is a motif developed from a children’s after school workshop that Ms Laila Tyabji, the Dastkar Chairperson, had initiated and facilitated. The motif was turned into a block print, and served as a popular product for tourists, who wanted to purchase a souvenir of their trip to the tiger reserve. Dastkar Delhi was instrumental in the development, and use of a range of animal block prints, that have been the key to the success of Dastkar Ranthambore’s past, and current, collections. The Tiger, along with the other animal block prints, continues to identify DR products, and makes them immediately recognizable, which has been central to creating the DR brand.

The key design inputs provided by the AEDAP designer were as follows;

|

|

The Right Mix An important element in DR’s success was the ongoing support it has received from Dastkar, a society for crafts and craftspeople, based in New Delhi that aims at improving the economic status of craftspeople, thereby promoting the survival of traditional crafts. It was founded in 1981 by six women, who had worked in the craft and development sector including Laila Tyabji, who is the current Chairperson. Similarly, the marketing support from AIACA, particularly through their Craftmark- Handmade in India, market access program provided export sale channels, and opportunities. In particular, the DR Manager, Ujwala Jhoda has been a key element in their success; her level of professional management meant that there was a fast turn-around time for sampling and sourcing new materials, so that design suggestions were put into action. Jhoda has operated DR as a business enterprise, ensuring high quality finishing of products, on time delivery, and consistent pricing; this has helped to build DR’s reputation amongst domestic and international buyers and led to repeat and new orders. According to Griffith, a good manager is essential for the success and growth of an enterprise and she believes that even with exceptional products, poor and incompetent management will mean that an enterprise can fail. In addition to their Manager, DR has embodied a culture of innovation, which has made it receptive to embracing change when it is needed. For instance, they were amongst the first hand block printing groups to install a water management system where waste water is collected and purified for reuse. From a marketing perspective, DR had a very strong story of women’s empowerment, poverty alleviation and community development to share with consumers and buyers, and this added value to the strong product line. |

| Postscript: Design as business development strategy The implementation of strategic design improved sales for DR, and generated income for its craft workers. Due to the impact the AEDAP design intervention had on DR’s sales, the organization now continues to work with designers, introduced, and set up by Dastkar, and including the Pearl Academy. The AEDAP case study demonstrates how appropriate design interventions can bridge the gap between traditional artisan skills and mainstream markets, and make a craft enterprise more competitive. |

The Nizams (r.1724-1948) of Hyderabad (present capital of Andhra Pradesh) are well-known for their gems and jewellery collection (Bala Krishnan 2001a: 28-37). However, their contribution towards costumes is less known so far is equally important and significant. In the field of costumes, Nizams have the credit of popularizing achkan, serwani, dastar and the western costumes. Under the influence of their Begums they patronized the traditional handloom also i.e. zari brocade pathani odhani and saree, ikat telia odhani and lot of embroidery decoration on the outfit (Morwanchikar 1993; Mittal 1962: 26-29). Besides traditional attire and western costumes Nizams promoted the gold embellishment on costumes and clothings, popularly known as masala-ka-kam. Among all the Nizams, the sixth Nizam, Mir Mahboob Ali Khan's contribution in the field of textiles is especially noteworthy. He was passionate for the good clothes, besides the jewels. To store his large collection of clothes, he built 72 m. (240 feet) long wardrobe at Purani Haveli, Hyderabad. The wardrobe was on either side of the hallway and had one hundred and thirty-three built in cupboards to accommodate his large collection of clothes, shoes, hats and accessories (Kumar 2006: 53). He was the first Nizam to wear western clothes and often wore western suit and English hunting gear, (Bala Krishnan 2001b: 15. The archival materials and photographs housed in various collections are the main source of information to know about the lifestyle of Nizams and their Begums. Apart from archival materials, the Nizam's actual costumes, clothings and furnishing materials, housed in Chowmahalla Palace. Purani Haveli and Salar Jung Museum (Vardrajan 2002: 23-51) at Hyderabad, also provides valuable information of fashion trend of that period. Some of the scholars' have worked upon on that, however objects belongs to Nizam's period but housed outside Hyderabad has been less studied and published, so far. In this context a painted ivory ganjifa set, which is in the collection of National Museum, New Delhi (Kedareswari 2001: 12; Bala Krishnan 2001: 14-25) is an important source of information for many things. The set of ninety-six ganjifa cards show well-dressed male and female portraits and their stylish attires, which makes this set unique. It also helps in analyzing the various outfits prevalent in the last quarter of nineteenth century of Hyderabad region, which is the main focus of this paper. Men's Costumes The first Nizam, Mir Qamur-ud-din (r.1724-1748) was initially appointed as the viceroy of Deccan by Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb. He was an able and brave leader and soon Mughal Emperor awarded him with the title Nizam-ul-Mulk Fateh Jung and later on with title ‘Asaf jah' from which dynasty was known afterward (Bala Krishnan 2001: 28-37; Kumar 2006: 24-48). The Asafphs adopted the lifestyle, court traditions and machinery of administration of the Mughals. Initially, the royalty and nobility of Hyderabad region had used Mughal style dress.. The available pictures illustrate Nizams in choga or jama or angrakha, as an upper garment and paijama as the lower garment (Kumar 2006: 48; Bala Krishnan 2001: 20). These were either made of fine muslin, silk brocade or velvet fabric, which were either woven or embroidered with metallic threads with beautiful floral patterns. These skillfully embroidered chogas were probably used as a ceremonial dress, which can be seen even in the coronation picture of the sixth Nizam. The sixth Nizam, Mahboob Ali Pasha, (r.1869-1911) and seventh Nizam, Mir Osman Ali-Pasa, (r.1911-1948) prefers the achkan and Serwani along with churidara paijama and dastar (turban in Turkish language). The seventh Nizam had worn red coloured brocaded silk serwani for his coronation in 1911, which is in the collection of Chowmahalla Palace collection in Hyderabad (Rao 1963; Prasad 1984). Gold brocade achkan, serwani with brocaded paijama and dastar of white colour was the favourite style of Nizams. Similar kind of attire is also visible in the ganjifa cards. The National Museum ganjifa set depicts less male figures. The first number of each ganjifa group (Pathak 2004: 449, 453, fig. 2, 8) of the set is always Maharaja, so there are eight male figures besides few in the gulam group. Male are shown either in tight fitting achkan or serwani along with churidara paijama as main attire. Turban or dastar and patka or belt can also be seen in most of the ganjifa card paintings. One thing is common in all the images of Maharaja that their garments were made of zari brocade fabric (fig. 29.1). Other male figures are shown in stripped or plain achkan or serwani and coloured paijama. The jama and angrakha are the close fitting attire, which has high waist portion, but wide flared skirt part. The length of attire falls sometimes up to the ankle. The latter one continued to be worn by the Hindu nobles until the 'early decades of the twentieth century particularly on ceremonial occasions. Somewhere in the last quarter of nineteenth century, the jama and angrakha were replaced by the achkan and serwani, which was probably created just to counter the European's tight fitted coat (fig. 29.2). The presence of French and British officials in royal court might have inspired the Nizams for adopting these buttoned chest coat style achkan and serwani. The shoulders of these silk brocade achkans and serwani have drooping curve like a coat, instead of straight shoulders of choga. The graceful flare of these costumes was tailored to a length just below the knee. During the last quarter of nineteenth century, jacket and waistcoat became fashionable among the royalty and aristocracy. These jackets and waistcoat were made of zari-brocaded fabric. With the good colour contrast these costumes were embellished with metallic threads (zari threads) depict beautiful floral motifs. The skilled local artisans use to do the beautiful, dazzling and bold karchobi embroidery work. With the upper garment ackhan and serwani, men use to wear paijama as lower garment. Paintings of the ganjifa cards depict two styles of paijama's during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. The first one was the tight fitting (known as churidara) and second one was the broad opening (known as tuman) paijamas. These paijamas were made of satin silk, zari brocade and masru material (Kumar 1999: 70, 74). Plain_ check or floral patterned paijamas generally illustrate vertical or horizontal striped designs. The Nizams use to wear patkas, the waistband, over the jama, which was wrapped around the waist and end panel falls on the front. As reflected in some of the early records that probably in the beginning Nizam’s wearing style of patka were influenced by the Mughals. These patkas were made of either lightweight cotton or silk materials, which usually have heavy end panels and borders woven with metallic threads. The end panels are either woven in Paithan or Chanderi or asavali technique or embroidered with zari threads. However, the later Nizams did not continue the same style and it became soon obsolete altogether in the early twentieth century. The sixth and seventh Nizams introduced the trend of using belt (Kumar 2006: 117-118) (fig. 29.3). In the beginning Asaf jahi's rulers had used the turban similar to Shah Jahani style headgear. Most probably the Mahboob All Pasa had introduced the smartly stitched turban in the shape of crown, known as dastar. The interesting aspect of the dastar is that certain colours were fixed for the use of certain people. For example the Asaf jahis wore fine muslin dastars only of bright yellow colour and adorned with torah a turban crescent), which nobody else was allowed to wear. The Paigah families (Salar Jung, etc.), who were the next important family after the royal, wore pink dastars and the colour for other nobles was also allotted according to their status in the court (Kumar 2006: 118). With the available archival information and ganjifa cards illustrations gives the view that the Nizams use to wear quite stylish attire and introduced many new outfit also, which slowly became fashionable from the end of nineteenth century. Women's Costume In the absence of the authentic records and actual costumes of first five Nizam's wives, it's very difficult to ascertain the authentic view of women's dress of that period. However, photo archive and costume collection of the sixth and seventh Nizam, which was housed in Chowmahalla Palace, gives some information. Here the ganjifa set of National Museum is an important work of art as it provides more information about female's costumes. Around seventy ganjifa cards depict female portrait out of ninety-six cards, which provide variations in their costumes and different wearing styles. The usual presumption is that Nizam's women also copied the Mughal Begum's Style (fig. 29.4). They use to wear peswaz, angrakhi, paijama and dupatta. Pesvaz is a front open long sleeve garment having tight fitted high bodice portion and flared skirt part, which has length up to ankle. Angrakhi is also an upper garment, which have tight fitted waist and flared skirt, however the length is not so long. Churidara paijama is like the men's one, however women use more patterned and bigger fabric for it. The dupatta is worn to cover the head and waist and its bigger portions falls in the front. The length and width of dupatta used in southern remain always bigger in compare to northern region odhani. Probably the term dupatta comes from Hindi word du and patta. The word du stands for two and patta or pat means fabric. When the usual width of odhani (odhani is a sort of fabric) is doubled from the normal odhani probably it is known as dupatta. The most interesting par is that women had worn dupatta in number of ways, as evident in the ganjifa cards set. As appeared from the photo archival records and costumes that women usually wear kurtii-choli-sidha paijama and khad dupatta in around late ninetieth century. The silk brocaded sleeveless kurta have distinctive keyhole neckline probably taken from peswaz (fig. 29.5). These kurtas were either woven with pattern or embroidered with metallic threads with intricate floral designs. Short sleeved choli were usually richly embroidered with badla, gota work and a kurta is worn over it. Sidha paijama is a tight fitting paijama, which has seam on the side, not in the front. Long dupatta is worn in such a manner that the full end panel falls on the front and popularly known as khara dupatta. These khara dupattas were usually woven or embroidered with bandobast or masla kind of zari embroidery work. The Chowmahalla Palace collection of costumes has some such dresses. In this collection some of the velvet and satin jackets and servani are richly embroidered with metallic threads and these were stitched for princess and other children. Sometimes net anrakhi or pesvaz's embroidered with mukesh work were also made for young prince or princesses. The close observation of National Museum's ganjifa cards gives the impression that three types of female costumes were prevalent in that period. The first group is of pesvaz/angrakha-paijama-dupatta/cap; second is the set of sari-choli and the third group is of choli-paijama-dupatta. Female illustration of the first group paintings is less in compare to other groups of paintings. The first group of paintings illustrates females, in rich and beautiful peswaz/ angrakha as the upper attire and churidara paijama as lower garment (fig. 29.6). The upper garment has tight fitting bodice and flared skirt portion. Front open peswaz's sleeves are full in length and lots of zari decoration gives the royal look. Women generally drape dupatta in two styles; either just placed on the left shoulder, like a stole, or covered the breast portion where both the end falls at the back. Second group of attire in these paintings are the sari-choli/blouse which are good in number (fig. 29.7). Most of the paintings show women in heavy zari brocaded sari worn in ulta pallu, where end panel of sari rest on the left shoulder and sometimes it covers the head (fig. 29.2). These heavy zari brocaded Bandrasi or Paithani saris were usually maroon, green. purple, royal blue and yellow in colour. Generally, these colourful brocaded saris were worn with contrast colour choli like; golden choli with maroon sari or maroon choli with yellow sari. The maximum number of paintings in this set is of the third group, which depicts females in short choli-churidara paijama-dupatta (fig. 29.8). Good contrast colour outfit is portrayed in these cards such as; maroon choli with golden paijama and purple odhani or yellow choli with orange paijama and blue odhani, etc. The wearing of dupatta is interesting, one end of dupatta is tucked in paijama from left hand side than covers she back and comes in the front than goes to the left shoulder from where it falls at the back. Apart from stitched garments, women of Hyderabad court and nobility use to wear sari also from last quarter of nineteenth century as portrayed in several ganjifa cards. In fact by 1910s and 1920s the sari was already being worn at the more progressive courts across the sub-continent. Around 1930s and 1940s photographs of Princess Niloufer, the senior daughter-in-law of Nizam VII (Mir Osman Ali Khan) shown her draped elegantly in silk saris (Kumar 1991: 70) . Although the sari collection of Chowmahalla Palace is rich and has variety; silk and zari brocade saris of Bandrasi, Asavali and Paithani. Besides silk saris cotton plain or striped saris are also in the collection, but less photographs are available in which women are wearing sari. These saris were woven with pure silk borders and end panels and perhaps woven somewhere in western Andhra or in southern Deccan. There were lots of art and artistic activities during the Nizam's period. Costumes, textiles, jewels, jewellery and decorative arts objects, were created in their period, which are still admired and loved by the people, who use to visit the Salar Jung Museum, Chowmahalla Palace and Purani Haveli at Hyderabad. In fact Nizams were the great patrons of traditional handlooms also, which is still being made by the dedicated weavers and embroiderers. Their love for best things have encouraged the weavers, embroiders to come from all over the world and they use to create dazzling and magnificent fabrics for their masters. Today's Servani, achkan, waistcoat, jacket, trousers were introduced during the Nizams period. Portrait paintings done on the small ganjifa cards are a beautiful evidence of variations of male and female outfit prevalent in that period. This is a unique example of last quarter of nineteenth century style in Hyderabad region. Notes

- Achkan and serwani is tailored right fitting coat like attire. Both these costumes are full in length up to the knee, full sleeves and have front open, which is buttons on the left panel to tighten the attire. Dastar is the stitched headdress like cap. Western costumes were shirt, trousers, coat and hat.

- Rahul Jain had worked on the exhibition of costumes and clothing's of Chowmahalla Palace in 2001-02 and a booklet has been published by the Nizam's trust.

- The ganjifa set has ninety-six small circular cards and a rectangular box for keeping the cards. High quality painting work done on these

- Masru is a colourful striped fabric, which is manipulation of cotton and silk yams in such a way that lusteres silk yam remain as upper surface, while cotton remain as lower yam, which come in contact of cotton yarn. Masru fabric is used for paijama and other stitched garments.

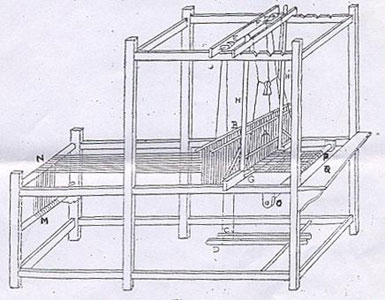

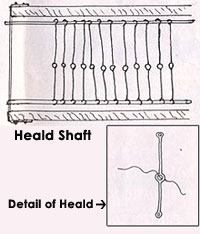

| Changing lifestyles and market structures mean that weaving is not a viable profession anymore. What's the way out?Hand-woven fabric is the product of Indian tradition, the inspiration of the cultural ethos of the weavers. With its strong product identity, handlooms represent the diversity of each State and proclaim the artistry of the weaver. It is not thread alone but the weaver's imagery, faith and dream that create heritage fabrics which have undoubtedly placed India on the world map. Handlooms rank second only to agriculture as an industry. The handloom sector boasts of 3.4 million weavers according to a census conducted by The National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) in the year 1995-96 whereas in 1987-88 it was 4.3 million and the drop of nearly a million is all too significant and in the present scenario rather bleak.The Kancheepuram sari with its korvai designs may become a museum piece sooner than we think, so also the cotton korvai saris, with the weavers disinterested in weaving them. A cotton sari fetches the weaver Rs. 270 per sari as against Rs. 2,500 for a silk sari. A master weaver in Kancheepuram quotes the example of an MNC which sends buses to pick up young adults who are the children of the weavers. Even if it is an unskilled laborer's job, he can pick up around Rs. 250-300 a day and what's more, there is "prestige" attached to a factory job! What's worse is that our Southern traditional weaves are being pirated through importing weavers from Tamil Nadu. For most handloom weavers it means sitting at a loom for 12 hours at a stretch and even longer if it is festival or wedding season. Many of those interviewed swear that they will not subject their children to work in a profession which drains them. Most of them develop orthopedic problems and then it is too late to move to other professions when they are past the prime of life.Indirect Impact "The adversities that the farming sector continues to face have considerably affected the survival of many subsidiary activities and are a strong contributing factor for the downfall of the weaving industry. This indirect impact cannot be ignored," says Dr. Shyamasundari of Dastakar Andhra. "While the weavers have encouraged their sons to be educated in professional courses, they have overlooked the fact that actually it is weaving that supported their education making them engineers and doctors." That the exodus of young handloom weavers from their traditional occupation is steady is all too apparent. Cheaper synthetic fabrics flooding the market is one of the reasons and of course the failure to access and adapt to newer markets. The market which was originally located in rural areas has shifted to urban areas. The weavers were selling their products to co-operatives but it is these co-operatives who have not been able to locate ready markets.One of the interventions by the Government is the Swarnajayanti Gram Swarozgar Yojana (SGSY); specially formulated to help the 19,500 weavers engaged in the production of low cost saris and dhotis for Free Distribution Scheme (FDS). The weavers, who in the past were capable of creative weaving, sank into a blissful state of complacency, knowing fully well that whatever they wove, or however bad the quality, it would be accepted. The number of saris and dhotis woven were much more than the number of beneficiaries and as a result, the godowns of Co-optex began to swell with stocks of these saris and dhotis. Consequently, the FDS had to be discontinued in 2001.Left Stranded Nearly 19,500 weavers were rendered jobless and faced severe socioeconomic problems. Highly skilled weavers, like the ones from Virudhunagar, who were weaving 80s by 120s, did not know how to recall their skill. It was a time of great unrest and these handloom weavers were in a state of flux. It was a Catch 22 situation. With powerlooms dominating textile production all over India, and encroaching on the handloom sector's traditional market, the handloom weavers, in a desperate situation, drifted towards powerlooms, finding that work here was an easy substitute. Children were sold as bonded labor to bosses and without money to release them the bondage looked permanent. They went into building construction and brick making besides other jobs. Even older weavers took to new occupations and traditional skills were fast languishing. The situation looked grimly bleak.A proposal was charted out for a special project which would help these weavers learn new skills, regain lost ones and gain exposure to the countless possibilities of fine weaving and the project planned in different stages such as identification of the project implementing agencies, skill and technology upgradation, entrepreneurship development, and infrastructure development. The State Government sanctioned 25.36 crores for the Project. NIFT became the implementing agency. Training has been imparted to the weavers and new designs have been developed in saris, dress material, shirtings, and household linen. New markets were located as also export markets.With the government doing what it possibly can, beneath all the fluff, there are layers of discontent voiced by the weavers. The main grouse is the fear that they would be left midway with new schemes that they find bewildering and the inability to access new markets based on past experiences. Besides, the psychological impact that a complete turnabout would bring is not really understood by the so called guardians of the traditional vocations. A great degree of sensitivity is required when working in these areas.Pawns in a Game Cut to the Varanasi weavers. A BBC World TV broadcast focused on the plight of weavers in Varanasi facing the impact of Chinese "Benares brocade saris" imported at a fraction of local prices. Again this is a story of utter poverty and despair and the weavers not wanting to remain tied to a crippling tradition. Thousands of weavers around Varanasi became pawns on the chessboard of a capitalist system of merchants, brokers and bureaucracy. Vilas Muttemwar, Congress Lok Sabha member from Nagpur, raised the plight of the region's weavers in Parliament, saying about 20 lakh weavers in Vidarbha were seriously hit by the government's "casual ad-hoc policy and unhelpful attitude" towards problems relating to supply of yarn, credit support and other related facilities. "As a result, a large number of weavers are on the brink of starvation," he maintained. Uzramma of Dastakar Andhra says that the handloom industry portrays a vibrant scenario even though it is in a state of flux. "The point to be made is that the State does not recognize its tremendous potential, not only for rural employment, but as a viable economic activity which does not need the huge investments of infrastructure and capital which conventional industries require," she says. So what are the options left to craft activists who are concerned at the plight of the weavers and a craft tradition which is languishing? Says Ashoke Chatterjee (former President, Crafts Council of India), "our finest craft skills need immediate protection, which means reaching the weavers at the apex of a pyramidal supply chain. The active participation of the trade is recommended, difficult though this may seem in the light of current attitudes and past experience. The present condition of decline in weaving reflects the changing social structures, values and most importantly changing markets. Simultaneously, working with authorities, NGOs and activists in and around Varanasi, or other affected areas, one could attempt a relief fund to address immediate survival needs of families affected by death, debt and starvation." The only solution as I see it is to lobby for the languishing craft and handloom weaver through press reports, the electronic media, plays, short films and whatever is needed to address the existing problems. Our Indian fashion designers have a wealth of traditional material to dip into and they could harness traditional skills to showcase their designs which could give the Indian weaver exposure in international markets. Without action the death knell sounds loud and clear. |