JOURNAL ARCHIVE

Ngarluma Ngurra: Aboriginal Culture on the map evolved from a creative initiative exploring the intergenerational transmission of Ngarluma culture and tradition through arts with a focus on tabi, the Ngarluma poetry and song tradition translated in paintings by artist Jill Churnside. From a return trip to Country undertaken as part of this endeavour, the project grew to encompass the broader Ngarluma community who were interested in exploring ways to document and record their intangible cultural heritage. In response to the Ngarluma elders desire to develop a platform which would support the transmission of knowledge to younger people, Sharmila Wood (FORM) and Andrew Dowding (Tarruru) developed the concept of embedding Ngarluma cultural values in a digital map; they brokered support from Google Earth Outreach and were the recipient of the grant which rewards organizations with outstanding mapping ideas. The map was built around a series of field trips undertaken with Ngarluma elders. Along with Ngarluma place names, film, audio, photographs and text identify particular sites around Ngarluma country, lending an insight into Ngarluma ways of seeing country. The map was launched on November 8th at FORM in Western Australia as part of a broader exhibition which curates paintings, song and objects of material culture together in order to present the richness and depth of Ngarluma culture.

Andrew Dowding is an anthropologist whose area of focus is intangible cultural heritage. He was a co-founder of the Ngarluma Ngurra: Aboriginal Culture on the map project with Sharmila Wood and conceptualized the cultural mapping methodology using Google Earth. Sharmila speaks with Andrew about the catalysts for the mapping project.

SW: Can you give us some background about how the Ngarluma Ngurra: Mapping Project began?

AD: The seeds for the project really emerged from my experience working with Ngarluma elders. These people are part of a generation who walked or rode horse back all over their Country - they didn’t use vehicles, and they have an intimate knowledge of the land because of that. These elders communicated to me that they would like to create a way to show how they are attached to places and how culture is related to these places in their Country. They wanted to document this information and make it accessible for future generations.

SW: How did you move from the need to create a way of representing Aboriginal cultural values about Country, into the digital sphere of Google Earth?

AD: Like many people I’ve used Google Earth for everyday general directions, and because I live down in Perth I really enjoyed being able to look at Ngarluma Country that I couldn’t visit in the Pilbara. It was through this function that I began to realise the power of being able to see distant places and the potential to overlay information about them. As my work progressed in the Aboriginal Heritage sector I continually saw a different application for Google Earth. I started my current work, which involved undertaking heritage surveys in the north of Australia, and I found that Google Earth helped me to visualise the places being depicted on paper maps because it gave details of the terrain, and you could see the car tracks and roads all over the land. These

SW: Can you give us some background about how the Ngarluma Ngurra: Mapping Project began?

AD: The seeds for the project really emerged from my experience working with Ngarluma elders. These people are part of a generation who walked or rode horse back all over their Country - they didn’t use vehicles, and they have an intimate knowledge of the land because of that. These elders communicated to me that they would like to create a way to show how they are attached to places and how culture is related to these places in their Country. They wanted to document this information and make it accessible for future generations.

SW: How did you move from the need to create a way of representing Aboriginal cultural values about Country, into the digital sphere of Google Earth?

AD: Like many people I’ve used Google Earth for everyday general directions, and because I live down in Perth I really enjoyed being able to look at Ngarluma Country that I couldn’t visit in the Pilbara. It was through this function that I began to realise the power of being able to see distant places and the potential to overlay information about them. As my work progressed in the Aboriginal Heritage sector I continually saw a different application for Google Earth. I started my current work, which involved undertaking heritage surveys in the north of Australia, and I found that Google Earth helped me to visualise the places being depicted on paper maps because it gave details of the terrain, and you could see the car tracks and roads all over the land. These things helped to orient me in the landscape and I soon saw the way other Aboriginal people found it easy to navigate and orient themselves as well. For instance, I was sitting in an office in Roebourne with an old man who has now passed away, and we travelled along old dogging tracks that he had made in his days working as a dingo hunter. He used to go out for months on end with only fuel drums and a gun, he would travel solo through very remote areas of Ngarluma Country, but because of his age he was no longer able to take me to those sites. But we were able to mark out a huge number of cultural sites by just sitting at the computer and viewing Google Earth. This was the first time I saw the power of Google Earth as a cultural heritage tool. Then, through Shakti and Elias from Curiousworks I saw how you could incorporate different media into Google Earth, from videos to photographs and audio. We’ve expanded this function to create a rich, content-driven map of Ngarluma Country using Google Earth, with the aim of using it as a platform for the protection and preservation of Aboriginal culture. We have asked community members to take us to a place they want to record content about, and we record it with a film crew, and then incorporate that into the map for others to learn about. This allows non-Aboriginal people to see how Aboriginal people understand land as being embedded with stories. By using high definition cameras, GPS and other new technologies, we are creating new cultural documents for people to use and refer too. things helped to orient me in the landscape and I soon saw the way other Aboriginal people found it easy to navigate and orient themselves as well. For instance, I was sitting in an office in Roebourne with an old man who has now passed away, and we travelled along old dogging tracks that he had made in his days working as a dingo hunter. He used to go out for months on end with only fuel drums and a gun, he would travel solo through very remote areas of Ngarluma Country, but because of his age he was no longer able to take me to those sites. But we were able to mark out a huge number of cultural sites by just sitting at the computer and viewing Google Earth. This was the first time I saw the power of Google Earth as a cultural heritage tool. Then, through Shakti and Elias from Curiousworks I saw how you could incorporate different media into Google Earth, from videos to photographs and audio. We’ve expanded this function to create a rich, content-driven map of Ngarluma Country using Google Earth, with the aim of using it as a platform for the protection and preservation of Aboriginal culture. We have asked community members to take us to a place they want to record content about, and we record it with a film crew, and then incorporate that into the map for others to learn about. This allows non-Aboriginal people to see how Aboriginal people understand land as being embedded with stories. By using high definition cameras, GPS and other new technologies, we are creating new cultural documents for people to use and refer too.

SW: You mentioned the idea of the map as a database, which suggests that you see it as a digital repository - How important is this aspect of the project?

AD: Well, the idea of bringing together information in a way that is free, accessible and public where appropriate, is something I feel passionately about. This is primarily because the elders I’ve worked with have expressed their desire to show that Australia is not empty of culture, that this is not an empty landscape devoid of any deep meaning and importance.

There have also been some experiences I’ve had that have influenced this belief. A turning point was discovering my grandfather’s recordings in an archive in Canberra. My grandfather was a prolific recorder of songs and stories, but getting access to these recordings was not the easiest process and I became very frustrated. When we did eventually repatriate them, I took the recordings to Roebourne and played them for elders, some of whom were very emotional about hearing my Grandfather’s voice again and there was a real sense of re-establishing a connection with traditional stories and the genre of songs called tabi. There was also a sense of pride that Ngarluma has this rich cultural body of stories, songs and poems that the elders were remembering and exploring again. These are really precious because they are a snapshot of cultural knowledge from the late 1960s and it demonstrated to me that because many of our traditional forms of passing on knowledge orally from one generation to another have been slowly eroded, that recordings and documentation are very important - as was having this material readily available for people to connect with.

The other important factor was going to New Delhi in India and working in the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (A.R.C.E). I saw how lacking Australia’s cultural infrastructure is, and how the real strength of A.R.C.E was their connection to communities. I began to see how archives were not only places for researchers to compile or hold materials, that they should not function in isolation from the people who own the content. Dr. Shubha Chaudhuri, the Managing Director of A.R.C.E, actively sought to engage the communities whose knowledge was stored in the archives by continuing to work with them, hand back materials and ensure ongoing cultural maintenance of their traditions.

SW: So the idea of mapping country in this way emerged from a combination of realising the possibilities that new technologies offered, but also the desire to create a digital archive that, as opposed to traditional archives, was accessible to the Ngarluma community and the wider public?

AD: Definitely. Over the past 100 years Aboriginal people have continually given information to people in government departments, in mining companies and researchers who have valued that material for the period that they have been engaged with Aboriginal communities, but then have made no attempt to repatriate it afterwards. It’s very sad because there is a lot of room to encourage this kind of repatriation in order for Aboriginal people to control and access their own socio-cultural information, now and into the future - particularly when the most common practice is for this information to be held in static archives that are located in places that are distant and foreign to the Aboriginal community.

The new frontier for archives all over the world is the movement towards digitising and repatriating, although this repatriation is not happening fast enough. Aboriginal people are frustrated because these precious resources are something that they want to utilise in order to teach their own communities about their history and culture. SW: You mentioned the idea of the map as a database, which suggests that you see it as a digital repository - How important is this aspect of the project?

AD: Well, the idea of bringing together information in a way that is free, accessible and public where appropriate, is something I feel passionately about. This is primarily because the elders I’ve worked with have expressed their desire to show that Australia is not empty of culture, that this is not an empty landscape devoid of any deep meaning and importance.

There have also been some experiences I’ve had that have influenced this belief. A turning point was discovering my grandfather’s recordings in an archive in Canberra. My grandfather was a prolific recorder of songs and stories, but getting access to these recordings was not the easiest process and I became very frustrated. When we did eventually repatriate them, I took the recordings to Roebourne and played them for elders, some of whom were very emotional about hearing my Grandfather’s voice again and there was a real sense of re-establishing a connection with traditional stories and the genre of songs called tabi. There was also a sense of pride that Ngarluma has this rich cultural body of stories, songs and poems that the elders were remembering and exploring again. These are really precious because they are a snapshot of cultural knowledge from the late 1960s and it demonstrated to me that because many of our traditional forms of passing on knowledge orally from one generation to another have been slowly eroded, that recordings and documentation are very important - as was having this material readily available for people to connect with.

The other important factor was going to New Delhi in India and working in the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (A.R.C.E). I saw how lacking Australia’s cultural infrastructure is, and how the real strength of A.R.C.E was their connection to communities. I began to see how archives were not only places for researchers to compile or hold materials, that they should not function in isolation from the people who own the content. Dr. Shubha Chaudhuri, the Managing Director of A.R.C.E, actively sought to engage the communities whose knowledge was stored in the archives by continuing to work with them, hand back materials and ensure ongoing cultural maintenance of their traditions.

SW: So the idea of mapping country in this way emerged from a combination of realising the possibilities that new technologies offered, but also the desire to create a digital archive that, as opposed to traditional archives, was accessible to the Ngarluma community and the wider public?

AD: Definitely. Over the past 100 years Aboriginal people have continually given information to people in government departments, in mining companies and researchers who have valued that material for the period that they have been engaged with Aboriginal communities, but then have made no attempt to repatriate it afterwards. It’s very sad because there is a lot of room to encourage this kind of repatriation in order for Aboriginal people to control and access their own socio-cultural information, now and into the future - particularly when the most common practice is for this information to be held in static archives that are located in places that are distant and foreign to the Aboriginal community.

The new frontier for archives all over the world is the movement towards digitising and repatriating, although this repatriation is not happening fast enough. Aboriginal people are frustrated because these precious resources are something that they want to utilise in order to teach their own communities about their history and culture.

SW: How is Google Earth different and why do you see this particular platform as aligning best with the needs of Aboriginal people?

AD: Generally, cultural heritage databases solely rely on the use of text. The importance of the online map is that it can demonstrate how Aboriginal culture is connected to land and is not just about being on Country, but is also about knowing your Country, which means knowing rivers, knowing the tracks that get you to those places, knowing the historical roots that are embedded in that country. We now have leaders in our community who agree it is important information that younger people should have access too. Google Earth is digital, it’s on the Internet, it can be accessed by multiple users and that’s the real power of the Internet: connectivity. There is now a new generation of Aboriginal kids who have mobile phones that are 3G enabled and they have the Internet in their hands. This map allows them to not only have access to their cultural information, but to see their elders and culture represented in an exciting digital format. I see a real need for Aboriginal people to forge a strong digital presence, for elders to harness these creative forces in this form of multimedia so they are in control of their digital identities. This will be a big part of the next ten years.

SW: How do you see Google Earth being used by Aboriginal communities in the future?

AD: With the promise of the National Broadband Network Aboriginal communities will begin to keep pace with the types of digital identities that communities all over the world are forming. It will take some innovation, and brave elders to step into that frontier, but we’ve already seen how the Canning Stock Route Project and others like the Mulka project in Arnhem Land, as well as Goolari Media in Broome, IcampfireTV. com and Juluwarlu in Roebourne are forming digital identities and creating multi-media. SW: How is Google Earth different and why do you see this particular platform as aligning best with the needs of Aboriginal people?

AD: Generally, cultural heritage databases solely rely on the use of text. The importance of the online map is that it can demonstrate how Aboriginal culture is connected to land and is not just about being on Country, but is also about knowing your Country, which means knowing rivers, knowing the tracks that get you to those places, knowing the historical roots that are embedded in that country. We now have leaders in our community who agree it is important information that younger people should have access too. Google Earth is digital, it’s on the Internet, it can be accessed by multiple users and that’s the real power of the Internet: connectivity. There is now a new generation of Aboriginal kids who have mobile phones that are 3G enabled and they have the Internet in their hands. This map allows them to not only have access to their cultural information, but to see their elders and culture represented in an exciting digital format. I see a real need for Aboriginal people to forge a strong digital presence, for elders to harness these creative forces in this form of multimedia so they are in control of their digital identities. This will be a big part of the next ten years.

SW: How do you see Google Earth being used by Aboriginal communities in the future?

AD: With the promise of the National Broadband Network Aboriginal communities will begin to keep pace with the types of digital identities that communities all over the world are forming. It will take some innovation, and brave elders to step into that frontier, but we’ve already seen how the Canning Stock Route Project and others like the Mulka project in Arnhem Land, as well as Goolari Media in Broome, IcampfireTV. com and Juluwarlu in Roebourne are forming digital identities and creating multi-media.  Personally, I feel it’s the Internet which will drive the next form of cultural innovation; up until now it’s been television and DVDs that have driven a need to record culture. However, with the Internet you can connect to a massive audience with relatively little infrastructure and make a real impact if you have good digital strategies in place. We’re hoping that more elders will adopt this form of mapping as a cultural teaching tool for their own communities, as well as educating the broader Australian community about the precious cultural resource they have in their own backyard. Aboriginal people have lived here for millennia, and have cultural, ecological and historical knowledge which is unique and needs to be acknowledged and valued. Personally, I feel it’s the Internet which will drive the next form of cultural innovation; up until now it’s been television and DVDs that have driven a need to record culture. However, with the Internet you can connect to a massive audience with relatively little infrastructure and make a real impact if you have good digital strategies in place. We’re hoping that more elders will adopt this form of mapping as a cultural teaching tool for their own communities, as well as educating the broader Australian community about the precious cultural resource they have in their own backyard. Aboriginal people have lived here for millennia, and have cultural, ecological and historical knowledge which is unique and needs to be acknowledged and valued. |

Mochi embroideries, which have found their way into museums the world over, are the topic of 'The Shoemaker's Stitch' by Shilpa Shah and Rosemary Crill.

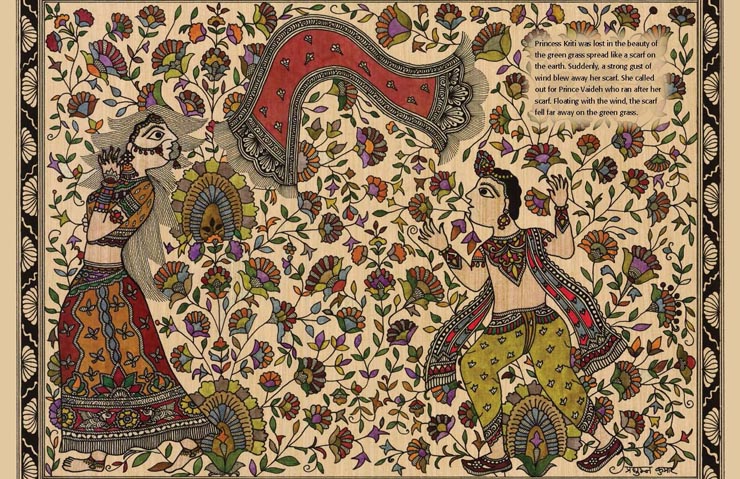

A example of Mochi embroidery from the book, 'The Shoemaker's Stitch'.

In the early 1990s, I began travelling regularly to Banaskantha in Gujarat, developing garments and soft furnishings for the Self-Employed Women’s Organisation (SEWA) with the women artisans in the region. Most were pastoral people, living in villages within a 100 kilometre circumference, their husbands mainly agrarian labour or cattle herders.

The area was a desolate, salty waste, prone to periodic droughts, extremely poor. Radhanpur was the nearest town. In one section, linked by winding lanes, were the small dark homes of the Mochi community. Traditional shoemakers once employed by royalty, they were now perilously poor, as fewer and fewer people ordered their beautifully embroidered leather juthis, preferring branded, industrially-manufactured shoes, or even plastic sandals.

The advent of the motor car also marked the demise of their elaborately embroidered leather trappings for elephants, horses and camels.

In order to eke out a living, the Mochis turned their hands to making generic embroidered ornamental wall hangings and cushions – in fabric rather than leather – for local traders and GURJARI, the Gujarat State Handicrafts Corporation. Few other employment opportunities existed.

As is customary, the men cut and stitched the items and the women filled in the embroidery, using the traditional aari –like a crochet hook or a cobblers awl, mounted on a wooden handle, unlike the chainstitch embroidery done in Northern India using a straight needle and working on a large, floor-mounted frame.

Similar Mochi communities existed in Bhuj and Mandvi in Kutch, as well as Saurashtra and Sind. In fact, many Mochi families traced their pedigree and craft from ancestors in Sindh who were brought to the Kutch court by Kutchi rulers in the 14th century and encouraged to teach their craft locally. Bhuj, as the seat of the Kutchi royal family, was the largest centre of Mochi embroiderers, now sadly diminished to a handful of families. A few beautiful old carved wooden houses, relics of better days, and some fine tombs, temples and mosques relieved the dusty poverty and small town clutter.

A example of Mochi embroidery from the book, 'The Shoemaker's Stitch'.

In the early 1990s, I began travelling regularly to Banaskantha in Gujarat, developing garments and soft furnishings for the Self-Employed Women’s Organisation (SEWA) with the women artisans in the region. Most were pastoral people, living in villages within a 100 kilometre circumference, their husbands mainly agrarian labour or cattle herders.

The area was a desolate, salty waste, prone to periodic droughts, extremely poor. Radhanpur was the nearest town. In one section, linked by winding lanes, were the small dark homes of the Mochi community. Traditional shoemakers once employed by royalty, they were now perilously poor, as fewer and fewer people ordered their beautifully embroidered leather juthis, preferring branded, industrially-manufactured shoes, or even plastic sandals.

The advent of the motor car also marked the demise of their elaborately embroidered leather trappings for elephants, horses and camels.

In order to eke out a living, the Mochis turned their hands to making generic embroidered ornamental wall hangings and cushions – in fabric rather than leather – for local traders and GURJARI, the Gujarat State Handicrafts Corporation. Few other employment opportunities existed.

As is customary, the men cut and stitched the items and the women filled in the embroidery, using the traditional aari –like a crochet hook or a cobblers awl, mounted on a wooden handle, unlike the chainstitch embroidery done in Northern India using a straight needle and working on a large, floor-mounted frame.

Similar Mochi communities existed in Bhuj and Mandvi in Kutch, as well as Saurashtra and Sind. In fact, many Mochi families traced their pedigree and craft from ancestors in Sindh who were brought to the Kutch court by Kutchi rulers in the 14th century and encouraged to teach their craft locally. Bhuj, as the seat of the Kutchi royal family, was the largest centre of Mochi embroiderers, now sadly diminished to a handful of families. A few beautiful old carved wooden houses, relics of better days, and some fine tombs, temples and mosques relieved the dusty poverty and small town clutter.

The Shoemaker’s Stitch’, Shilpa Shah and Rosemary Crill, Niyogi Books, 2022.

Working on fabric was nothing new to the Mochi community. In the past too, the most skilled craftspeople custom made beautiful garments, accessories, canopies, and wall panels in silk, satin and mashru for the local nobility, and even for more far-flung royal patrons.

The workmanship was extraordinary, the aari used like a miniaturist’s paint brush; the embroidery, delicate configurations of foliage, flora and fauna – peacocks and parrots for fertility; elephants, lions and horses for power and wealth; decorative borders overflowing with the roses and lilies and flowering trees seldom seen in those dry climes.

Verdant Trees of Life were a popular theme, as were Sri Nathji pichwais to hang behind the deity in the temples. Extraordinarily fine work was being done both on leather and fabric well into the 20th century, declining post-Independence, coinciding with the decline of the Nawabs and Maharajas who were their patrons.

It is these Mochi embroideries, mainly of the early 19th century, that are the subject of The Shoemaker’s Stitch, the latest documentation of TAPI’s wonderful textile collection.

Shilpa Shah, co-founder of the TAPI Collection of Indian Textiles and Art, is also co-author of this book. Her inspirational work, collecting and documenting Indian textiles, follows on from Gira Sarabhai and the Calico Museum in the 1950s and 60s. Her travels all over India and Master’s degree from Berkeley University endow her with both academic and personal insights, as well as passion and love.

Her co-author is Rosemary Crill, former Senior Curator at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, who has studied and written on Indian embroideries and textiles over the years. Their combined expertise and scholarship make this book an intensely pleasurable read – both visually and in its content. On its part, Niyogi Books has done a wonderful job of photography, printing and design. The Shoemaker’s Stitch is a a joy in everything except its considerable weight!

The book documents items from the Kutch, Dhangadhra and Jaipur royal family collections, the V&A and other Western museums as well as pieces from the TAPI Collection itself. It is superbly illustrated: the rich, vivid reds, greens and yellows and ornate, heavily-worked motifs of the Mochi embroideries, often boldly outlined in black, highlighting their difference from the more subtle, delicate Persian and Mughal influenced chainstitch of Northern India and Bengal.

Even pieces commissioned for the European Market have a distinctive difference from the crewel work of Kashmir or the painted chintzes of the Coromandel coast. As Shah points out, Mochi embroideries travelled to courts and temples all over India, and therefore, have often been mistakenly identified as local work. To the trained eye, they are very different, both in imagery and execution.

The Shoemaker’s Stitch’, Shilpa Shah and Rosemary Crill, Niyogi Books, 2022.

Working on fabric was nothing new to the Mochi community. In the past too, the most skilled craftspeople custom made beautiful garments, accessories, canopies, and wall panels in silk, satin and mashru for the local nobility, and even for more far-flung royal patrons.

The workmanship was extraordinary, the aari used like a miniaturist’s paint brush; the embroidery, delicate configurations of foliage, flora and fauna – peacocks and parrots for fertility; elephants, lions and horses for power and wealth; decorative borders overflowing with the roses and lilies and flowering trees seldom seen in those dry climes.

Verdant Trees of Life were a popular theme, as were Sri Nathji pichwais to hang behind the deity in the temples. Extraordinarily fine work was being done both on leather and fabric well into the 20th century, declining post-Independence, coinciding with the decline of the Nawabs and Maharajas who were their patrons.

It is these Mochi embroideries, mainly of the early 19th century, that are the subject of The Shoemaker’s Stitch, the latest documentation of TAPI’s wonderful textile collection.

Shilpa Shah, co-founder of the TAPI Collection of Indian Textiles and Art, is also co-author of this book. Her inspirational work, collecting and documenting Indian textiles, follows on from Gira Sarabhai and the Calico Museum in the 1950s and 60s. Her travels all over India and Master’s degree from Berkeley University endow her with both academic and personal insights, as well as passion and love.

Her co-author is Rosemary Crill, former Senior Curator at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, who has studied and written on Indian embroideries and textiles over the years. Their combined expertise and scholarship make this book an intensely pleasurable read – both visually and in its content. On its part, Niyogi Books has done a wonderful job of photography, printing and design. The Shoemaker’s Stitch is a a joy in everything except its considerable weight!

The book documents items from the Kutch, Dhangadhra and Jaipur royal family collections, the V&A and other Western museums as well as pieces from the TAPI Collection itself. It is superbly illustrated: the rich, vivid reds, greens and yellows and ornate, heavily-worked motifs of the Mochi embroideries, often boldly outlined in black, highlighting their difference from the more subtle, delicate Persian and Mughal influenced chainstitch of Northern India and Bengal.

Even pieces commissioned for the European Market have a distinctive difference from the crewel work of Kashmir or the painted chintzes of the Coromandel coast. As Shah points out, Mochi embroideries travelled to courts and temples all over India, and therefore, have often been mistakenly identified as local work. To the trained eye, they are very different, both in imagery and execution.

An image from the book showing a woman wearing an outfit made of Mochi-embroidered fabric.

Looking at earlier craft and textile traditions, it is easy to fall into despair about their present status. However, all is not gloom, as the concluding chapter of The Shoemaker’s Stitch tells us.

There has been a revival of aari bharat, and many designers and practitioners are making wonderful contemporary pieces, though not always crafted by traditional Mochi embroiderers. Asif Shaikh, Arun Virgamya, Adam Sangar and their extended families, the Shrujjan Museum and Shobhit Mody are some that come to mind.

Working with the Mochi, Ahir and Meghwal embroiderers in Radhanpur, SEWA and Dastkar have produced beautiful wall hangings that have found a home in many national and international museums and venues, often combining the three local textile skills of patchwork, mirrorwork and aari bharat.

Mochi Bharat is no longer the preserve of male craftspeople but has given hundreds of women independence and earning, adding yet another important dimension to the practice.

An image from the book showing a woman wearing an outfit made of Mochi-embroidered fabric.

Looking at earlier craft and textile traditions, it is easy to fall into despair about their present status. However, all is not gloom, as the concluding chapter of The Shoemaker’s Stitch tells us.

There has been a revival of aari bharat, and many designers and practitioners are making wonderful contemporary pieces, though not always crafted by traditional Mochi embroiderers. Asif Shaikh, Arun Virgamya, Adam Sangar and their extended families, the Shrujjan Museum and Shobhit Mody are some that come to mind.

Working with the Mochi, Ahir and Meghwal embroiderers in Radhanpur, SEWA and Dastkar have produced beautiful wall hangings that have found a home in many national and international museums and venues, often combining the three local textile skills of patchwork, mirrorwork and aari bharat.

Mochi Bharat is no longer the preserve of male craftspeople but has given hundreds of women independence and earning, adding yet another important dimension to the practice.

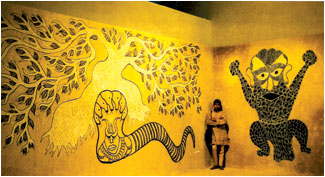

As winter settles down upon my quiet New England hometown and I observe the most recent snow that has fallen on our streets and sidewalks, I can't help but think of those living further north where the wind blows colder and the days are only too brief. Recently, the Peabody Essex Museum, in Salem, Massachusetts, displayed an exhibit of craft, art and film from Inuit people in the arctic north, in their gallery space created specifically for rotating installations of Native America art. And on a blustery winter day in late December, I had the fortunate experience of stumbling onto this exhibit. The exhibit, titled Our Land: Contemporary Art from the Arctic, is the first major exhibition of art and craft from the Canadian territory of Nunavut, which lies in northwest North America just inside the Arctic Circle. Nunavut, created in 1999 after the Canadian government reformulated its territories, spans from the Hudson Bay to the North Pole and houses ecologies that range from barren vistas to mountains to the silent but lively oceans. These harsh yet beautiful conditions act as only a part of the inspiration for Inuit art in Nunavut. Our Land was born from a collaboration between the Peabody Essex Museum, the Government of Canada and the Government of Nunavut's Department of Culture, Language, Elders and Youth, and is part of an on-going series at the Peabody Essex Museum that focuses on Native American art and culture. This series also falls in line with the museums commitment "to forging partnerships with Native American artists through projects such as the Education through Cultural and Historical Organizations (ECHO)." The Inuit art and craft on display during the exhibition ranges in medium from stone, leatherwork, pottery and textiles on the craft side to lithographs, drawings, sculpture, photography and film on the fine art side. Although the forms and mediums of all the pieces varied greatly, the significance behind each and its source of inspiration clearly came from one unified origin: the culture and spirit of the Inuit people. Karen Kramer, assistant curator of Native American Art, along with John Grimes, deputy director for research, new media and information, curated this exhibit around the themes of cosmology and spirituality, families, place, season, time and gathering. In order to explore Traditional Inuit Knowledge, or Inuit Qaujimajtuqangit, more deeply through the exhibit, Kramer organized the works into three sections. The first section considers Being where works that focus on cosmology and spirituality explore the responsibilities and challenges of the Inuit people in the modern world. In the second section, works that emphasize Family, where traditional knowledge is reinforced and acquired, display images of individuals, the community and the nuclear family, and examine themes like individual identity within a culture. Lastly, the third section examines works which highlight Community and the way in which traditional knowledge is preserved throughout time, place and season in a changing social context. What is interesting about Inuit art and craft is the unique implementation of technology, both modern and ancient, each artist or artisan uses. For example, an artisan may create a stone Inuksuk, literally "likeness of a person," which acts as cairn or landmark to identify a specific place of significance in the endless and barren tundra. The creation of cairns is an old method of marking the land used in traditional societies the world over. In terms of new technology, Inuit artists have melded traditional Inuit themes like family, nature and survival with modern mediums such as film. These endeavors have met with great success. In Zacharias Kunuk's film Atanarjuat or The Fast Runner won the Camera d'Or for Film Debut at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival. In the Our Land exhibit, Kunuk's other film Nunavut is incorporated into a video installation and highlights Inuit art's auspicious advance into the fine art world. However, Inuit craft and art still hangs in a precarious balance where traditional artisans struggle with the influences and appeals of modernization. Much like Indian folk art Inuit craft strives for survival in this ever-accelerating world that requires constant stimulation. In both cultures artisan must deal with issues of authenticity, preserving images, meaning and significance while bending to market trends in order to earn a living from the beautiful items they create. In Inuit North America however, there is lack of directly accessible markets due to its remoteness and harsh environmental conditions. Instead Inuit artisans must turn into artists and rely on the acceptance of the fine art world where their images, stories and culture can live on. For more information about Inuit Art, Culture and History go to the Peabody Essex Museum's web site where there is a list of resource web sites, interviews with Inuit artisans and singers and a video link which depicts the construction of a stone figure or inuksuk at the museumhttp://www.pem.org/exhibitions/exhibition.php?id=36

In 'Imprints of Culture: Block Printed Textiles of India', Eiluned Edwards shares the voices of craftspeople while also analysing government and NGO programmes. [caption id="attachment_198229" align="aligncenter" width="405"]

Block printing is one of India’s oldest forms of surface ornamentation on textile. Credit: Pixabay[/caption]

Our textile traditions owe much to numerous intrepid and indomitable aficionados over the decades who have travelled the length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent, falling in love with, documenting and developing our extraordinary skills. A surprising number of these people have been foreigners and women. Starting with Flora Ann Steel and phulkari, whether it is the research of Stella Kramrisch, Rosemary Crill, Susan Bean, Sheila Paine and Vickie C. Elson, or the design sensibilities of Faith Singh, Judy Frater, Brigette Singh and Maggie Baxter, their passion and insights have added greatly to what has been done by our own textile gurus: Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Gira Sarabhai, Pupul Jayakar, Prabha Shah, Nelly Sethna, Jasleen Dhamija, Martand Singh, Jyotindra Jain, Rita Kapur Chishti, Lotika Varadarajan, Aditi Ranjan, Rahul Jain, et al.

Block printing is one of India’s oldest forms of surface ornamentation on textile. Credit: Pixabay[/caption]

Our textile traditions owe much to numerous intrepid and indomitable aficionados over the decades who have travelled the length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent, falling in love with, documenting and developing our extraordinary skills. A surprising number of these people have been foreigners and women. Starting with Flora Ann Steel and phulkari, whether it is the research of Stella Kramrisch, Rosemary Crill, Susan Bean, Sheila Paine and Vickie C. Elson, or the design sensibilities of Faith Singh, Judy Frater, Brigette Singh and Maggie Baxter, their passion and insights have added greatly to what has been done by our own textile gurus: Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Gira Sarabhai, Pupul Jayakar, Prabha Shah, Nelly Sethna, Jasleen Dhamija, Martand Singh, Jyotindra Jain, Rita Kapur Chishti, Lotika Varadarajan, Aditi Ranjan, Rahul Jain, et al.

Eiluned Edwards Imprints of Culture: Block Printed Textiles of India Niyogi Books, 2016

Eiluned Edwards, the author of Imprints of Culture: Block Printed Textiles of India, is a name to add to this list. A reader in global cultures of textiles and dress at Nottingham Trent University in the UK, she has been coming to India for decades. Her earlier book, Textiles and Dress of Gujarat (2011), was an invaluable insight into the costume traditions of this craft-rich state. Block printing is one of India’s oldest forms of surface ornamentation on textile. The Harappans knew how to weave and dye in 2000 BC. Although embroidery, not printing, is mentioned in the Vedas, ornamenting cloth by printing probably followed soon after. Our development of mordants to fix dyes and create different colours, and our varied complex techniques of resist and surface printing, meant that printed Indian fabrics were soon in demand all over the world. Fragments of ajrakh resist prints dating back over 12 centuries have been found in the Fustat excavations in Egypt, and the “sprigged muslin” worn by Jane Austen’s heroines were our familiar delicate Sanganeri and Farrukhabad floral butis. Aristocratic European 17th and 18th-century interiors were full of the all-over floral kalamkaris of Macchlipatnam, referred to as Chintz. So popular were Indian Chintzes that the French, seeing the impact on their own textile industry, banned their import and sale. Sadly, the advent of roller printing in the 19th century and the British substitution of their own manufactured cotton goods for handwoven Indian ones killed this flourishing international trade. It’s ironic that the wonderful British Raj documentations of Indian hand block prints were intended as design references to be duplicated mechanically by British manufacturers. Equally ironic, these records, stored in British museums, now serve in their turn as inspiration for 21st-century Indian block printers. “Trade and economics are the heart of textile crafts,” says Edwards. Indian craftspeople are among our most skilled professionals, especially valuable since few other countries possess these knowledge systems. Nevertheless, they live an uncertain existence, unvalued, unrewarded and unconsidered. When the Krishna canal is closed by the Andhra Pradesh government every May/June, there is no work for kalamkari workers.; left waterless, they are unable to print and wash for the two months. When master ajrakh printer Abdul Jabbar Khatri writes to the author, “Sister, business is very good. Inshallah, we will eat goat many times this year”, it is a poignant indication of how little they expect, how much more they deserve. What I love about this wonderful book is that it is all about “people and processes”, as Edwards says in her introduction. So many similar books have pages of gorgeous museum pieces, but no information on who, how, where or what is happening in these craft areas now. That only works for a coffee table book. This book is not just full of the voices and stories of craftspeople, it also tracks the impact of government policies, NGOs, designers and retailers in the sector, encompassing the Handicrafts Board and Gurjari, the Crafts Councils, Anokhi and FabIndia, and Sabyasaachi. There is even Dastkar. [caption id="attachment_198231" align="aligncenter" width="353"] Eiluned Edwards. Courtesy: Indian Saris blog[/caption]

All craft history is a composite of the social, cultural, economic, aesthetic and technical. This volume has it all – the influences of caste, region, gender and location that help preserve skills within regions and families, the effect of government and NGO livelihood schemes that have drawn in women and others outside the community who did not traditionally practice the craft, thus increasing numbers but also diluting quality and integrity. Then there are changes that the use of computers, smartphones and WhatsApp have made possible. The potential and perils of a growing but fickle consumer base. The fact that block printing is marketed as “green”, but seldom addresses the issue of toxic chemicals and water pollution.

As I write this, hand block printers all over India are firefighting the impact of the newly-imposed GST. Given that hand block printing, like many other craft traditions, is a series of processes done by different sets of people, and therefore every part of process is a separate transaction that now needs to be invoiced and recorded, and also given that a single craftsperson makes multiple kinds of products, with most of the sales made in temporary bazaars far away from their place of origin, the compliance requirements and additional costs are mind-boggling. Periodically, one has wondered how long these ancient but now alternative forms of production can survive. This threat seems closer than ever. Books like Imprints of Culture are vital in reminding us of our fortune in still having these living traditions, and how important it is to protect and preserve them.

My only caveat is that it is far too heavy. Impossible to read comfortably, either at one’s desk or in bed. Nevertheless, we owe Niyogi Books a huge debt of gratitude for publishing it.

Eiluned Edwards. Courtesy: Indian Saris blog[/caption]

All craft history is a composite of the social, cultural, economic, aesthetic and technical. This volume has it all – the influences of caste, region, gender and location that help preserve skills within regions and families, the effect of government and NGO livelihood schemes that have drawn in women and others outside the community who did not traditionally practice the craft, thus increasing numbers but also diluting quality and integrity. Then there are changes that the use of computers, smartphones and WhatsApp have made possible. The potential and perils of a growing but fickle consumer base. The fact that block printing is marketed as “green”, but seldom addresses the issue of toxic chemicals and water pollution.

As I write this, hand block printers all over India are firefighting the impact of the newly-imposed GST. Given that hand block printing, like many other craft traditions, is a series of processes done by different sets of people, and therefore every part of process is a separate transaction that now needs to be invoiced and recorded, and also given that a single craftsperson makes multiple kinds of products, with most of the sales made in temporary bazaars far away from their place of origin, the compliance requirements and additional costs are mind-boggling. Periodically, one has wondered how long these ancient but now alternative forms of production can survive. This threat seems closer than ever. Books like Imprints of Culture are vital in reminding us of our fortune in still having these living traditions, and how important it is to protect and preserve them.

My only caveat is that it is far too heavy. Impossible to read comfortably, either at one’s desk or in bed. Nevertheless, we owe Niyogi Books a huge debt of gratitude for publishing it.

Export Capacity Assessment for the Vietnam Craft Sector Aid to Artisans & Handicraft Research & Promotion CentreVietnam’s growing craft sector offers opportunities for traditional artisans across the nation to build livelihoods and preserve their cultures. It represents one of the top ten industries for export revenues in Vietnam, providing thousands of artisans with incomes and opportunities. In recent years, the Vietnamese Ministry of Industry and Trade has recognized the earning potential of handcrafts and set targets of US$1.5 billion in annual craft exports by 2010, with the US market being a major target market to reach this goal. This trend differs from just six years ago when Europe remained the largest source of export sales for Vietnamese handcrafts accounting for 44% of the market.1 However with the series of US-Vietnam Textile Agreements initiated in 2003, sales of Vietnamese handcrafts to the United States have increased making it “the number one importer for Vietnamese home decorations and handicrafts for the last three years [2003-07].”2 Although sales to the US have allowed Vietnamese craft exports to improve, artisans continue to face strong competition from China and Thailand. In addition, the declining U.S. economy has the potential to weaken craft exports to the United States eroding Vietnam’s current main export market. Background Despite the Vietnamese craft sector’s sophistication and supportive government polices there is a continuous need to improve access to market information, product development services, production capacity and market linkages. In order to understand the necessary inputs to assist the Vietnamese craft exporters in reaching these targets, Aid to Artisans partnered with the Handicrafts Research and Promotion Center to conduct a study of the current Vietnamese craft export sector. With support from the Ford Foundation in Vietnam, an Aid to Artisans consultant conducted a marketing assessment of the Vietnamese craft export sector. This assessment was implemented in collaboration with the Handicrafts Research and Promotion Center and with the invaluable assistant of Le Bang Ngoc, HRPC Project Manager and Senior Craft Expert.Aid to Artisans (ATA), a non-profit organization, offers practical assistance to artisan groups worldwide, working in partnerships to foster economic development, improved livelihoods, cultural vitality and community well-being. Through collaboration in product development, business skills training and linkages to new markets, ATA provides sustainable economic and social benefits for craftspeople in an environmentally sensitive and culturally respectful manner. ATA's uniqueness lies in its multi-faceted and holistic approach to artisan enterprise development, which is designed to provide sustainable economic and social benefits to artisans and their communities. ATA works with artisans across the globe and currently has 20 projects across four continents. ATA benefits 20-25,000 artisans per year through projects and grants (with 2/3 being women), and in FY07 leveraged more than $15 million in new sales for artisan businesses.The Handicrafts Research and Promotion Center (HRPC) is a Vietnamese non-profit organization which works in partnership with disadvantaged artisans and marginalized groups. HRPC focuses its efforts on developing the Vietnamese crafts sector to improve livelihoods and foster community development. HRPC promotes handcraft villages and works with disadvantaged people by providing development services such as product design, business skills training and market linkages. Methodology The assessment was primarily done through interviews and stakeholder meetings with select exporters and craft development agencies. The focus of the interviews was on logistical infrastructure for local and export market access, products, artisan groups, input suppliers, such as raw material and packaging supplies, and potential partnerships. In conducting this research, the ATA consultant traveled to Hanoi for one week to conduct interviews with craft exporters and development organizations about the future of craft exports from Vietnam. The goal of this trip was to better understand the current needs and the challenges Vietnamese craft exporters and development workers face, particularly when working with poor, rural and minority artisans. Key Findings The environment in Vietnam is ripe for expanding craft marketing both on local and international levels. The country has a mix of traditional skills and factory production, as well as a blend of producers with production capacities to meet a variety of needs. Local programs and government sponsorships are targeting growth and are prepared to offer assistance to developmental organizations interested in developing the craft sector. The government is currently addressing long term sustainability issues and the international market is ready for more products and production from the range of producers that Vietnam has to offer.

VIETNAMESE HANDICRAFTS

Vietnam has a long tradition of creating beautiful and complex handcrafted items. The majority of these skills have lasted through the centuries in traditional village production and through incorporating them into modern, commercial production. Current handcraft production in Vietnam is not only a way for rural and ethnic minority artisans to generate income but it also serves as a form of cultural revitalization, safeguarding traditions and ancient ways of life. Vietnam hosts over 2,000 craft villages spread throughout the nation with the majority of these being in the northern region of the country. Artisans from these villages create traditional handcrafts in a range of media including ceramics, lacquer ware, silk, cotton and hemp weaving, embroidery, wood carving, bamboo, natural fibers and rattan products. The resulting products display the variety of skills and traditions that Vietnamese artisans possess and illustrate the deep and rich culture heritage of the nation.3 Producer Structure Vietnam has three primary types of producer groups that include the traditional craft village, factory production and ethnic minority artisans. Each group consists of a range of organizations which vary in size, corporate structure and production capacity. The consultant conducted interviews with a spectrum of businesses and developmental groups, both governmental and non-governmental. All of these groups from the most rural micro-enterprise artisan businesses to the large, sophisticated factory production units fall within the Vietnamese Government’s classifications of handcrafts. Ethnic Minorities: The ethnic minority producer groups are comprised of artisans that use traditional skills to create products primarily for use within their own communities. These groups are mainly based in the northern region of Vietnam and are the most difficult to reach directly due to poor infrastructure. While no interviews were conducted directly with individual artisans from these groups, interviews were held with several Hanoi partners, including Craft Link4 and governmental development offices, who work with ethnic minority artisan groups. Ethnic minority artisans have high skill levels and low production capacity. Language barriers, remote geography, lack of capital investment and inadequate business skills are significant issues with these groups. Several development and cultural revitalization programs are targeting these groups in an effort to preserve the traditional skills and culture of the region. Craft Link has worked with groups of ethnic minorities for more than 20 years and has built their business employing these producers. Seventy percent of Craft Link’s production is fulfilled by ethnic minority groups and they have created a skills training program to continue to develop these artisans. Craft Link works with more than 56 producer groups employing over 5,600 artisans throughout Vietnam. They have been able to successfully link rural producers to export markets as well as maintaining several local stores and consignment venues in luxury hotels. Craft Link’s business structure contains two arms including both marketing and artisans/business development. Originally the organization began with external funding and support but is now able to support both the marketing and craft development arms of the business with incomes from sales of handcraft products. The ethnic minority artisans, also known as hill tribes, are also being targeted for cultural revitalization through programs such as SNV’s (Netherlands Development Organization) pro-poor tourism development.5 These programs offer experiential travel in unique remote areas to visit indigenous groups. By providing commercial outlets for artisan made products and cultural experiences, SNV’s program hopes to create income for ethnic minority villages and revitalize their cultures. With the exception of a few buying groups such as Craft Link, most of the products from these tribes are for local and tourist consumption. Product development and external market access are limited to non-existent. Traditional Craft Villages: The traditional craft villages are a network of craft producing villages that were created to increase efficiency in the supply lines of handcrafts. The villages increase incomes in rural areas without a dependency on agriculture and decrease rural-urban migration. Each village was created based on the need for specific skills and/or products. There are approximately 3,000 of these villages which represent a wide range of products, skills and raw materials from silk to ceramics to woven natural fibers. The villages that the ATA consultant visited in and around Hanoi are quite developed with tremendous production capacity. For example, Van Phuc Silk Village produces more than 2 million meters of silk annually. About 1,300 families in this village generate 90% of their income from the annual $6 million in regional sales. Most of the production done in these villages is sold to local and regional buyers, with some villages providing piecework employment for local factories. Product development support and innovation is limited within the villages and few of the groups have outside marketing programs. Most villages rely heavily on buyers looking for high volume production opportunities. The network of these villages is extensive and government export programs target them for international production. Many of these villages have good infrastructure for and experience with international packing and shipping requirements. Factory Production: Factory production of handcraft is a growing sector in Vietnam. Large production facilities are being built in and around many traditional craft villages to further increase efficiency. The factories are coordinating production exclusively for export to western markets in the US and Europe and many are shipping hundreds, if not thousands, of containers annually to retailers such as IKEA, Pier 1, Wal-Mart, Williams Sonoma, Pottery Barn and Cost Plus. The factories are using the traditional skills of the artisans within the villages to produce piece-work components for goods which are finished in the factory setting. Several of the groups the consultant visited had in-factory staff of more than 1,000 and village producers numbering 30,000 or more. All of the product and production falls within the governmental definition of handcraft creating stiffer competition for rural and traditional producers. The factory production groups are the most sophisticated of all the producers and often exhibit products in international marketing venues and tradeshows. Since export markets remain their primary focus, local sales are an insignificant and sometimes non-existent factor in their business. Product development is primarily client driven and sophisticated. Additional product development implemented by the business itself is only conducted for showcasing skill sets at international venues. Assistance Needed The existing network of craft exporters is fairly extensive in Vietnam with the majority of “handcraft” export coming from the factory coordinated production of the traditional craft villages. Overall, all of the three producer group types require product development and improved market access in order to increase export sales. However, the specific training, product development and marketing needs of each group require immensely different inputs. The ethnic minority groups require domestically based partners to successfully export due to barriers in communication and infrastructure. In this situation it would be best to work through and with a domestically based partner to provide basic skills and business development training as well as product development geared specifically toward the export market. These groups need assistance in developing marketing linkages and local distribution to the domestic retail market and regional distribution groups which would then export products. Although some national level organizations, such as Craft Link, are successfully exporting goods from ethnic minority artisan groups, the main markets for expansions include the tourist market and the domestic Vietnamese market. The traditional craft villages and the factory producers offer the greatest opportunities for increased export sales. The Vietnamese Government has set targets for handcraft exports sales to increase in the next 5 years, reaching over $1.5 billion USD. These two groups have the capacity and business skills to work in an international environment. They are capable of timely and clear communication and possess computer, banking and business skills, although some groups lack full English language skills. In order to increase export sales from traditional craft villages and factor production groups, they need high volume sales through exposure to the large international retailers and other high volume buyers. A plan for their expansion should include securing raw material supply lines through regional markets since resources in Vietnam are limited. Much of the current volume production involves raw materials that either have restrictions on procurement or sustainability issues. Wicker, rattan, bamboo and wood are in limited supply in Vietnam and their harvest is currently under government regulation. However, many of these restricted raw materials are now being imported from neighboring countries including Burma, China, Thailand and Cambodia where land restrictions are fewer and managed crops are available. The traditional craft villages and factory product units can increase their market presence through improving their network of buyers and through direct selling opportunities such as tradeshows. There are regional tradeshow in Vietnam, Thailand and Hong Kong which focus on export sales and the Vietnamese Government even sponsors buyer participation from the US and Europe. In order for these organizations to increase their export sales they need to have a larger presence in international markets and increase their networks of buyers. References- Le Ba Ngoc. (2003). Craft Products in Vietnam. Retrieved March 18, 2008, from Handicrafts Research and Promotion Web site:-http:/hrpc.com.vn/craftproducts.html

- VNA. (2008). Hand-made Products to Rake in 1 Billion in US Exports. Retrieved March 18. 2008 from Vietnamese Business Finance Web site:-http:/www.vnbusinessnews.com/2008/03/hand-made-products-to-rake-in-1-billion.html

- Since the purpose of this study is to review the current craft export sector and determine necessary input to increase craft exports from Vietnam, the author did not focus on reviewing Vietnamese crafts. For more detailed information on the specific craft of Vietnam please see the Handicrafts Research and Promotion Center at-www.hrpc.org and the Vietnamese Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism at-http:/english.cinet.vn/Default.aspx.

- Craft Link is a leading not-for-profit organization working with artisans in Vietnam on income generating projects with a particular focus on ethnic traditions in northern Vietnam. For more information visit their websitehttp/www.craftlink.com.vn

- SNV, supported by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, promotes sustainable development by means of generating production, income and employment opportunities and improving access to basic services. For more information about their Pro-Poor Tourism initiatives in Asia visit their website:-http/www.snvworld.org/en/regions/asia/ourwork/Pages/tourism.aspx

Issue #009, 2022 ISSN: 2581- 9410 Creating a sustainable cycle of Organic Desi Cotton. Nothing can so quickly put the masses back on their feet, as the spinning wheel can. Charkha the Life line of India Mahatma Gandhi COTTON: The Magic Fibre: Cotton fibre gradually becomes hollow during its growth, turning from a solid rod to a spirally twisted hollow tube on maturity. The porous structure allows air to pass through and makes it uniquely absorbent, able to hold 20 times its own weight in water. The capillary action allows cotton to be the most suited cloth for humans. It keeps us cold in summer sand warm in winters. The 6 yard cotton trees that Marco Polo saw in Gujarat no longer exist, and what he described as ‘the finest and most beautiful cottons that are to be found in any part of the World’ no longer woven. Indian cotton dates back to Harrapan civilization & we made the finest cloth in the world called Dacca Muslin. This legendary Ducca Muslin was dubbed aab-e-rawan (Running water), shabanam (Evening dew), beft hawa (woven air), because it would float like a cloud if thrown in the air. India became the ‘Sone ki Chriya’, the golden bird, because of the Cotton it traded. Until the British came and systematically took it apart making us a marginalised cotton textile industry. Every part of India has its own indigenous variety of Cotton, that was suited to that environment. Short staple was the variety that grew in India. With the coming in of the British, they started promoting Long staple varieties to suit their mills to mass produce Cotton cloth to cater to the World demand’s. From the largest producer of the finest Cotton in the World India gradually lost out. In the recent years BT & GMO Cotton varieties were introduced. These varieties are high yielding but come at a high price, they need a lot more water, chemical for the land and lots of pesticides. With erratic rains, climatic changes, poor remunerative prices, lack of institutional credit and irrigation, it set the scene of devastation. Monetary losses across the cotton belt over years leading to massive Famer suicides in Vidarbha and other regions. A lot of cotton areas have now shifted to other lucrative crops. We have lost again. 54% of the total pesticides used in Indian agriculture are sprayed on Cotton alone, although it only accounts for 5% of the cultivated area. Cotton that clothed us for a thousand years is being slowly replaced by artificial fibre. Is Cotton is now a niche fibre ? A fibre that was considered utilitarian, beautiful and lasting. Now only exists as a burden on the land, on the water as a resource, heavily sprayed with toxic pesticides and chemicals.

I am working very hard to revive the lost glory of Indian Cotton that was traditionally grown in this region.

I have found age old cotton (desi) seeds that were grown in this region a long time a ago (Hapur, Uttar Pradesh).

These are Short staple, they are grown organically with no pesticides, no chemicals. They are hardy and pest resistance and most importantly they are Rain fed with no irrigation what so ever.

We want to use this fibre as a source that joins and builds communities. Cotton as the fabric of the Future, you wear what you weave. The charkha, which was the mainstay of cloth production in pre-colonial times, was transformed into a symbol of resistance to the British rule. Similarly I think the cotton that we grow can become a connecting thread into the Future.

Our Design Studio will create New Age Social Enterprises and Business Models adding to India’s Creative Economy.

We grow Organic Indigenous Cotton,

We clean, comb and card it locally,

We build a community across villages to use the charkhs to spin the yarn, increase livelihood possibilities and preserve hand spinning.

We use the local weaving community to make the cloth, creating a sustainable way to preserve the dying art of handmade.

We bring in designers to come, collaborate with us to make it reachable to the new generation.

Our Collaboration with Himanshu Shani has been very rewarding.

His company 11.11.in is one of the most important sustainable Brands from India.

Our Collaboration was first showcased at Lakme Fashion Week in 2019. It opened the Sustainable Week in Mumbai.

Our AIM:

I am working very hard to revive the lost glory of Indian Cotton that was traditionally grown in this region.

I have found age old cotton (desi) seeds that were grown in this region a long time a ago (Hapur, Uttar Pradesh).

These are Short staple, they are grown organically with no pesticides, no chemicals. They are hardy and pest resistance and most importantly they are Rain fed with no irrigation what so ever.

We want to use this fibre as a source that joins and builds communities. Cotton as the fabric of the Future, you wear what you weave. The charkha, which was the mainstay of cloth production in pre-colonial times, was transformed into a symbol of resistance to the British rule. Similarly I think the cotton that we grow can become a connecting thread into the Future.

Our Design Studio will create New Age Social Enterprises and Business Models adding to India’s Creative Economy.

We grow Organic Indigenous Cotton,

We clean, comb and card it locally,

We build a community across villages to use the charkhs to spin the yarn, increase livelihood possibilities and preserve hand spinning.

We use the local weaving community to make the cloth, creating a sustainable way to preserve the dying art of handmade.

We bring in designers to come, collaborate with us to make it reachable to the new generation.

Our Collaboration with Himanshu Shani has been very rewarding.

His company 11.11.in is one of the most important sustainable Brands from India.

Our Collaboration was first showcased at Lakme Fashion Week in 2019. It opened the Sustainable Week in Mumbai.

Our AIM:

- Create a value chain for Organic and Natural Farming.

- Make our farm a Demo for Farm to Fashion.

- Celebrate and preserve India’s rich heritage of traditions.

- Support and honour rural artisan communities.

- Provide livelihood opportunities for women.

- Support the revival of regenerative, localised craft value chains from Farm to textile & farm to Table.

- Revive and preserve ecologically sensitive, endangered crafts, principally: natural dyes, hand-spinning and handloom weaving.

- Stand as a beacon of excellence in the growing conversation around the preservation of handmade textile and the promotion of sustainable design

- Create a dynamic platform for artistic exchange, innovation and education at Hapur Organic Farm

FUTURE

In the coming future Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Robotics with takeover functional jobs. Machines can do things with precision and in time.

Then What will the larger section of our society do ?

We need to upskill ourselves.

Everyone in smaller cities and villages aspire to move to a big city. They either become daily wagers or end up driving an uber. Example : A traditional bricklayer or artisan or farmer, having lived in poverty, will always aspire that his child goes to cities and takes up some other profession. It takes very little ability to do the above but what we end up losing is 4 or 5 generations of skill and wisdom. A brick layer or a weaver migrating is a huge loss.

Our ability is asymmetry, Made by Hand, triggering the emotional retina. Using traditions and larger wisdom that has sustained the test of time to cater to the new generation Living and co exiting in harmony in the coming future

My work here should compel people to stay comfortably at home in their village and live with pride doing what they love doing with pay that matches the city.

Source of some of the information above is from ‘A Frayed History : The Journey of Cotton in India ‘ by Meena Menon and Uzramma

FUTURE

In the coming future Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Robotics with takeover functional jobs. Machines can do things with precision and in time.

Then What will the larger section of our society do ?

We need to upskill ourselves.

Everyone in smaller cities and villages aspire to move to a big city. They either become daily wagers or end up driving an uber. Example : A traditional bricklayer or artisan or farmer, having lived in poverty, will always aspire that his child goes to cities and takes up some other profession. It takes very little ability to do the above but what we end up losing is 4 or 5 generations of skill and wisdom. A brick layer or a weaver migrating is a huge loss.

Our ability is asymmetry, Made by Hand, triggering the emotional retina. Using traditions and larger wisdom that has sustained the test of time to cater to the new generation Living and co exiting in harmony in the coming future

My work here should compel people to stay comfortably at home in their village and live with pride doing what they love doing with pay that matches the city.

Source of some of the information above is from ‘A Frayed History : The Journey of Cotton in India ‘ by Meena Menon and Uzramma

Issue #10, 2023 ISSN: 2581- 9410 If we look into evolution of the human race it has been because of the constant development of the species need for survival as well as curiosity that from clothing oneself with animal hide, living in caves and forest shelters, to using natural cut rocks as troughs, leaves as containers, wooden stumps as building blocks to now where there is a new fabric being developed every day, architects building structures nearly reaching the sky and utility equipment that are robotic in nature is because of the deep understanding of the environment and ecosystem in which the human being lives. The evolution of the human race began from the need for survival in the large diverse animal kingdom that it is a part of. First, protecting itself from the other animal species some of whom were bigger and fiercer. Then an environment which was ever changing in climatic conditions from heat to rain and cold. Finally, just the diversity in the land they lived on, with thick forests, to dry sandy dessert, to cold ice desserts, huge towering mountains, rocky terrains and large rivers with the vast oceans. Just like other animal species even the human beings had to constantly keep figuring out ways and means to stay alive which has technically not changed even in the 21st century only the ways and means differ in the current times. Understanding these basic needs made every human being in the Dark Ages and all the other evolutionary stages, a designer, because one was constantly finding solutions to new challenges they faced, and it had to be found in the environment around them. And it was the same trees, rocks, rivers that they lived in that offered them the solutions. That is the fibre or basis of the evolution of the human race. Up until the 200 years ago, most of what we evolved into as a human being anywhere on the planet used materials available in nature for all our needs. The first aircraft was built using wood and fabric; the first long distance voyage ships were made of wood and their sails with cloth; the cooking utensils were made from clay; iron ore; stone; fire was always wood fire and then coal for energy; clothing was animal hide; wool; cotton; bast fibres; silk. Each of these materials discovered and used by the race as per their need for that environment and weather. Human beings evolved from being one species to several with the creation of clans/tribes. I believe the inspiration of setting up groups amongst themselves would have come from them learning from other animal species who always moved as a herd and each animal species have several herds which also helps them demarcate their territory which is done mainly for the basic need for food. Humans too created their own packs for food, shelter and protection. It’s the setting up of these clans/tribes that created a need for building identities, to show a sign of strength or territory because unlike the other animal species who through their 6th sense live almost respectfully of each other and instinctively know their place in the larger animal kingdom, this is an instinct that was absent in the human beings. Hence for identity they created symbols they wore on themselves, which were tattoos, headgears, their clothing, their weapons. Many of these once again inspired by observing other animal species around them. These pieces of identity once again were made using the natural materials available to them in their environment. Once these identities were established, then, is where the need to show power and hierarchy began and so humans grew in material culture which is a practice even today. Even today it is the brand of your hone/clothes/shoes/accessories; your car or the number of cars; the size of your house that give you a status and a place in the social order prevalent today. The entire evolution of the human race is based on the material available to them at that period of time to overcome the challenge of security; identity and hierarchy, and the basis of it all is the Fibre. The minutest part of any material if broken down completely is the atom, a group of atoms form molecules and the collection of molecules for the visible fibre or particle which then creates different structures. The fibre as we all know is not just the basis of creating thread to be twisted for weaving or knitting or knotting but is the building block for any tangible object around us. We are progressing as a race making every aspect of our lives more comfortable by constantly adding a new object everyday to fulfill a “new” need, due to which the sensitivity towards its evolution, the processes, the people, the community, the ecosystem that has enabled it to be created is being lost. This uncaring attitude because of an abundance of material things being made easily available has made us a race that has become more of a “taker” than a “giver” creating waste and increasing pollution. We need to go back to the basics and we need to pay attention to the seed of a story in order to continue to let the planet be our biggest provider. There are many practitioners today apart from the traditional artisan communities who continue to practice their indigenous craft and way of living, like artists; designers; entrepreneurs ; social organisations ; academics ; innovators who are working with this intrinsic idea of the Fibre being the basis of all creation. This journal of fibres is a compilation of a few of these stories from this community. The story of evolution and its deep connect with the basis of life – the fibre is an unexplored realm from the context of social and cultural heritage conservation, preservation, and growth. The intents of this journal on Fibres is to begin this conversation at the human level.