JOURNAL ARCHIVE

Issue #002, Winter, 2019 ISSN: 2581- 9410

|

In this context of globalization and growing extension of modern communication techniques, there is paradoxically a quest for quality, identity and originality. While countries, individuals and groups are more and more committed to combining the ability to participate in the world of technology and open markets with the promotion of their cultural heritage, it is not surprising therefore that tourism has moved from the 3 S (sun, sea and sex) to the 3 E (entertainment, excitement and education). How then can we make the best of this favorable wind of change to further promote crafts development? - Address by Mr. Indrasen Vencatachellum, UNESCO Representative, at the Closing Ceremony of the International Workshop on Tourism and Crafts. Tourism is the largest industry in the world and directly employs about 36 million of India’s people. Although the effects of tourism on the craft industry have yet to be thoroughly studied, the 6.8 millions tourists that visit South Asia every year clearly provide India’s artisans with opportunities for sales and direct market feedback. In reports from the Asian Development Bank, experts forecast that tourists into South Asia will reach at least 18.8 million visitors by 2020, which will undoubtedly bring billions of dollars into the region. However, all is not positive. The tourism industry has had to deal with the threefold blow of 9/11, SARS (and now the Avian Flu) and the war in Iraq. These factors made 2003 the worst year on record for global tourism, with a decrease of nine million worldwide tourist visits from 2002. Clearly the biggest threat to tourism is the feelings of uncertainty that travelers daily face when presented with images of bombsites and war ravaged villages and growing concern over health statistics and death tolls. India’s place in this overwhelming uncertainty is often vague. Although, India receives far more visitors than its surrounding South Asia neighbors, she still deals with an image that contains threats to safety and health as well as a location close to unstable nations with anti-western sentiments. With India’s artisans facing all these challenges in addition to their daily struggles, how can they learn to harness the power of tourism to develop their craft sectors? As with all marketing efforts the first rule it to identify the customers. The type of tourists visiting places in South Asia has not shifted much over the years with the majority of them being long-haul visitors who place value on experiences, authenticity and low prices. Of course, India also sees her fair share of short stay visitors who come with specific reason and spend much on luxury hotels, spas and goods. However, with the current global situation, even these short stay visitors are acting more spontaneously, staying much closer to home and spending less. Both type of tourists are beneficial for artisans in India, given that their specific needs can be met. Long-haul tourists are less likely to spend on goods in general since their budget is limited and their luggage small. They will spend on crafts, like textiles, that are easy to carry or ship and less expensive than other media. For example in the UNESCO Crafts/Tourism Index, UNESCO ranked the top selling craft categories to tourists in Burkina Faso as textiles, jewelry, wooden objects, bamboo and other natural fibers and leather. These categories will obviously change per country but the fact that tourists are more interested in small, easy-to-carry and less expensive items remains. Short stay tourists are, of course, more likely to spend more money in a shorter period of time and be less discerning about the size and weight of their purchases. Even though tourism overall may be struggling, the future of crafts in tourism is seeming brighter. Globalization has been often criticized as a westernization of the world, however it has created an enthusiasm about cross-cultural learning for some. Looking at trends in tourist spending and societal shifts, strong consumer excitement and awareness for sustainable tourism is predicted. In 2003 Eco-tourism accounted for about 20% of tourist spending, with the potential for growth. Eco-tourism, often described as culturally and environmentally sensitive, can include outdoor adventures as well as authentic cultural experiences in crafts villages or elsewhere. Bhutan is a prime example of a country that has placed high value on eco-tourism, not only to increase tourist spending but more importantly to preserve Bhutanese culture. For example Bhutan’s National Ecotourism Strategy states that eco-tourism is “Styles of tourism that positively enhance the conservation of the environment and/or cultural and religious heritage and respond to the needs of local communities”. Although there is much further to go in developing the tourist market, the potential that already exists is great. UNESCO’s Crafts/Tourism Index pointed out that in some cases “the direct sales to tourists of crafts items brought a larger income than exports. In Thailand, for example, tourists purchases of crafts products amount to almost 2 billion US Dollars, surpassing the total national exports.” With proper assistance and a market driven plan, crafts both in India and across the globe can harness this potential to the benefit of both the artisan and tourists as they learn more about cultures worldwide. References UNESCO Crafts/Tourim Index, Paris May 2004, Mr. Dominique Bouchart Asian Development Bank, South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation Plan |

|

The craft or handicraft sector is the largest decentralised and unorganised sector of the Indian economy. Craftspeople form the second largest employment sector in India, second only to agriculture. Handicrafts are rightly described as the craft of the people: there are twenty-three million craftspeople in India today. In India, craft is not merely an industry but a creation symbolising the inner desire and fulfilment of the community. While handicrafts, be it metal ware, pottery, mats, wood-work or weaving, fulfil a positive need in the daily life of people, they also act as a vehicle of self-expression, and of a conscious aesthetic approach. The artisan is an important factor in the equation of Indian society and culture. By performing valid and fruitful social functions for the community, they earn for themselves a certain status and position in society. S/he is the heir to the people's traditions and weaves them into his/her craft. Most craft people have learned their skills from their fathers or mothers since caste and family affiliations, rather than training or market demand, have primacy in the Indian situation. The handicrafts sector is a home-based industry which requires minimum expenditure, infrastructure or training to set up. It uses existing skills and locally available materials. Income generation through craft does not (and this is important in a rural society) disturb the cultural and social balance of either the home or the community. Many agricultural and pastoral communities depend on their traditional craft skills as a secondary source of income in times of drought, lean harvests, floods or famine. Their skills in embroidery, weaving, basket-making are a natural means to social and financial independence. The craft sector contains many paradoxes. Artisanal contribution to the economy and the export market increases every year and more and more new crafts-people are being introduced into the sector - especially women - as a solution to rural and urban unemployment. At the same time mass-produced goods are steadily replacing utility items of daily use made by craftspeople, destroying the livelihood of many, without the concomitant capacity to absorb them into industry. However, with ever-increasing competition from mill-made products and decreasing buying power of village communities due to prevailing economic conditions, artisans have lost their traditional rural markets and their position within the community. There is a swing against small scale village industries and indigenous technologies in favour of macro industries and hi-tech mechanised production. Traditional rural marketing infrastructures are being edged out by multinational corporations, supported by sophisticated marketing and advertising. The change in consumer buying trends and the entry of various new, aggressively promoted factory produced commodities into the rural and urban market, has meant that craft producers need more support than ever if they are to become viable and competitive. As a socio economic group, artisans are amongst the poorest. Research shows that households headed by artisans, in general have much lower net wealth and almost all (90%) are landless as against 36% for households headed by others. The average income derived by a craftsperson is Rs 2000 per month for an average family of five members. The current state of India’s artisans is a matter of serious concern. Government Policies since the early twentieth century have emphasised generating employment and increasing export earnings through crafts, but in spite of this most craft people live in abject poverty. Though some have managed to adapt to changing times, and a few even thrive most of them live in dismal poverty with no prospects for a better tomorrow. In the face of constant struggle, most artisans have given up and moved away from their traditional occupations. The skills, evolved over thousands of years, are being dissipated and blunted. Research indicates that neither the crafts persons, nor their progeny want to join the crafts sector, only a lack of available alternatives forces them to do so. They would not mind the tradition coming to an end. In one of the studies by Jaya Jaitly (2001), she reveals that in more than half the traditional leather artisan households, several family members have given up leather work, and are working as casual labourers. The new economic and industrial order that is emerging concedes no space to the artisanal sector. There are number of reasons for the craft people’s current state: from the lack of capital to invest in raw materials to a scarcity of raw materials and their availability at reasonable rates; from the absence of direct marketing outlets to difficulty of access to urban areas that are now the main markets for craft products, from production problems to a lack of guidance in product design and development based on an understanding of the craft, the producer and the market - the constraints are many and varied.

I will examine the efficacy of the craft sector providing a sustainable livelihood option through a project initiated in Rajasthan. Urmul Marusthali Bunkar Vikas is a weavers society with a membership of 120 weavers, 100 of them are men and twenty women, spread over eleven villages. They belong to the Meghwal caste (a caste that figures in the lowest rungs of the caste hierarchy in the region- the ‘Dalit’ community) the traditional weavers of this particular belt of Rajasthan. Weaving offers them an employment opportunity and means of livelihood to support their families in the hard desert condition (the area has been classified as one of the most backward in the country, in terms of both productivity and accessibility). Formally registered in 1991, UMBVS owes its genesis to the famine relief activities undertaken by Urmul Trust, a Non-Government Development organisation based in Bikaner district, Rajasthan. In 1986-87, Rajasthan suffered a severe drought and Bikaner was one of the worst affected districts. It became imperative to provide employment to people faced with near starvation. Searching for alternative means of employment, the spinning of wool into woollen yarn - a traditional activity carried out by the women in the region, stood out as a possibility. The raw material was local, as were the skills and the market for the product. Urmul Trust bought wool, distributed it among the women for spinning and made payments as per the labour per kilogram of yarn spun. As the stock of wool piled up, the Trust realised that the local market could not absorb the quantities that were being produced. A search for markets and outlets for spun woollen yarn led Urmul Trust to locate weavers in Jodhpur and Jaisalmer districts. With them, Urmul Trust struck a deal: that weavers would use the yarn supplied by the Trust, and in turn the Trust would purchase everything they produced, paying on a piece rate basis for the value-added services provided by the weavers. Subsequent developments led Urmul Trust to locate and move a few weavers in Jaisalmer district to the Urmul Trust campus in Lunkaransar with twin objectives, to help these weavers improve on their traditional designs, while simultaneously training local people in Lunkaransar how to weave, there by providing them with a sustainable livelihood option. For the next two years, a group of five weavers lived in Lunkaransar, training for and learning the demands of bigger markets. The practice of obtaining spun wool from the Trust, weaving and stocking finished products with the Trust continued. The Trust was responsible for the sale of the finished products. In June 1988, the Trust organised a meet, where about hundred and twenty weavers from villages in Bikaner, Jodhpur and Jaisalmer gathered. The mela (fair) was the first of its kind in Rajasthan and an opportunity for weavers across three districts to interact. The decision to establish an independent weaver’s organisation was taken here. People at Urmul Trust were sceptical - the enterprise was running at a loss - the weavers themselves were not sure, but they were determined to try it out. After much discussion and argument the proposal was adopted and the Urmul Marusthali Bunkar Vikas Samiti was born. The five weavers that had been based in Lunkaransar shifted the base of operation of the new organisation to where they belonged (400 kms from Lunkaransar). On loan to them for a period of six months, the Trust placed four professionals who helped the weavers with marketing, production, accounting and design. Within a few months, the weavers took charge of their business. Office bearers were chosen, systems were set in place, work was delegated and positions in the organisation filled. It was decided to ask the weavers to make a contribution of Rs1000 each towards the new society. This inculcated in each of the members, a sense that they owned a piece of the society, that it was ‘theirs’. This fund was used as capital and the profit / loss at the end of the year was shared by the members. They requested Urmul Trust to take back two of the four staff. In early 1991, the weavers went ahead with the formal registration of UMBVS, and made a profit of Rs 270,000 for distribution amongst the weavers. They had done in one year what the Trust had not been able to in two years - make a profit! Twelve years since the society was established the weavers get fair returns for their weaving. 70% of the cost of production goes to the weaver as weaving cost. As the women of the house help in the pre-weaving process, 30% of the amount goes to them. 50% of the profit accrued by the overall sale of the products goes back to the weavers in the form of a yearly bonus. Regular training programme are conducted to increase the number of weavers and in development and up gradation of weaving skills. The weaver’s benefit from a yearly bonus, interest free loans, compulsory savings and individual life insurance. The exposure and motivation that some UMBVS members received from Urmul Trust, led UMBVS to look beyond their economic development programme. Today, apart from uniting rural artisans and keeping alive their traditional craft, the organization has adopted a sustainable development approach. Starting with weaving activities in five villages in the two districts, UMBVS is working in a total of 45 villages of Jaisalmer and Jodhpur District of Western Rajasthan, with interventions in areas of education, health and economic development of ‘Dalits’ (Meghwals) and women. It runs fourteen schools, has formed ten women’s collectives with a savings of Rs 20,000 (Urmul, 2001). The weaver community of Meghwals used to be temporary migrants. Almost the entire family moved in search of employment to nearby areas, during the difficult periods prior to the agriculture season. With membership in UMBVS the migration of weaver families has completely stopped. They have built resources, a means of livelihood for the household to fall back on even if market trends, government policies, financial constraints hamper their production or marketing temporarily. The earnings from crafts supplement the household income to sustain their livelihood. UMBVS is responsible for creating a mass awareness of the craft; it provides job security and steady income for the weavers. Its success lies in the fact that ‘weaving’ is a traditional craft, besides the fact that all the weavers belong to a close-knit community. They operate with controlled membership after proper training. UMBVS gives the weavers social prestige and an immense feeling of belonging- coupled with a feeling of ownership, as they control and run the entire organisation. Rajasthan has been severely affected by the recurring drought for three years (1999 onwards). Hundreds of people had to migrate in search of work or were in heavy debt of the middlemen in order to support their families. Though the weavers faced problems because of shortage of water and due to climatic conditions, as compared to the other villagers they have been much better off as their work has secure returns. The weavers (UMBVS) case study demonstrates Urmul Trust’s attempts to incorporate the local knowledge of a grassroots organization’s, and its efforts and takes into consideration existing social structures and social relationships. This helped in strengthening the organization and the analytical abilities of its members, ensuing their complete access and control over assets, processes and decision-making. Both economic gain and a dignified status in society for craftspeople are necessary and possible if they are to be recognized and supported in the many roles they serve. A holistic approach to the development of the crafts sector is needed; focused around livelihoods, social development and environment of the artisans. The many and varied constraints, including the lack of capital, scarcity of raw material, disappearing markets, declining wages and technological obsolescence (to name a few) need to be tackled to improve the production capacity and to assist the artisans. Emphasis needs to be on a much greater effort at widening and strengthening policies to sustain livelihoods in which craftspeople are already skilled and productive.End Notes

|

Only a few centuries ago, in pre-industrialised India , almost everything that served a purpose in daily life was made by hand using simple tools and locally available raw materials. Ranging from utilitarian products to highly decorated and complex ones, the staggering diversity was a result of the creative interplay between form and function, between material and process and between meaning and expression. A variety of influences which included climatic conditions, religious and cultural beliefs, availability of raw materials and a definitive aesthetic were the matrix out of which sprang this vast multitude of objects made for clothing, ornaments, personal decorations, ritual and votive offerings, the built environment and much else. The cycle of making and usage was perfected over several hundreds of years in a number of different ways.The gathering together of artisans in markets in villages was perhaps one of the earlier systems . It was usually held in specified locations and provided a pre-determined point of exchange. The sale was made directly from maker to consumer and would probably have included the barter system of trading . Interestingly, this system continues to this day both in rural and urban areas and the volume of business transacted in some of these markets can be quite substantial. In contrast, during the Moghul period a large section of handcrafted production was organised in workshops which produced highly embellished and decorative articles as well as textiles mainly for the use of the royalty and the aristocracy. Paintings, woodwork, jewellery, jade work, bronze and weapon making, inlays both in wood and stone and the superb textiles made during this period reflect the direct involvement of the patron. Such objects and textiles were also enriched by designs and techniques which show influences from other civilisations. Another way of trading, that of export, has a very early origin. For several thousands of years Indian textiles have been bartered and exchanged in trade with countries stretching from China to the Mediterranean. Through overland and maritime routes these textiles were traded as commercial commodities made to the requirements of a foreign consumer. Entire townships in India were sustained by this demand for many hundreds of years. Export of textiles to the East was also significant and catered to niche markets like the royalty in Thailand. It was during the colonial rule and immediately afterwards in the transition to industrialisation in the last century that the many of these known channels of trade for hand crafts and textiles suffered large scale disruption affecting the livelihoods of the millions of artisans who produced them. The slow mode of production and fragile inter-dependent system of trading prevalent for many centuries was shattered by the onslaught from mechanised production. 'Technological' advances and other discoveries of the time also had their own adverse effects , the discovery of synthetic dyes in the West almost killed the unrivalled production of natural dyed cloth in India. The challenges that the artisan had to face in order to survive in this changed climate were manifold. On the one hand, some of the traditional handcrafts had to find different, usually urban markets in which they could be sold, and on the other hand, the new markets thus found were looking for products which would compliment a new way of living, thus an element of design and adaptation had to be introduced. With the markets and the clientele receding and becoming more and more distant, the artisan in rural areas was often dependent on an intermediary. Many of the NGOs ( non governmental organisations ) who worked for the sector were impelled to take on this pivotal role but it was inevitable that some private enterprises proved to be exploitative. One of the first organised attempts soon after independence at marketing crafts in retail was the the iconic Central Cottage Industries Emporium ( popularly known as the Cottage). Cottage was started by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay in 1952 and was able to effectively showcase the diversity and richness of Indian handicrafts sourced from many different parts of the country. Kamaldeviji's dedication and energy soon made Cottage a true repository of Indian crafts known all over the world. It became profitable enterprise as well ; many branches were soon opened across the country. Along with the Cottage Emporiums, several State Emporia were also opened in New Delhi. Brilliant in its concept, that of bringing before the urban public, authentic crafts from the various states of India, within some years official indifference and lack of vision ensured that barring a few the rest had lost their pre-eminent role in promoting crafts. Many years later, the Dilli Haat , modelled on the bazars prevalent in many rural parts of India was opened in Delhi. This unusual and interesting effort was the result of a partnership between Dastakari Haat Samiti , an NGO and Delhi Tourism ( a governmental body). It was built on a long strip of land reclaimed by building over an existing nala ( waste water channel) in the centre of Delhi. Space here was at a premium and would normally have been impossible to obtain. Along with crafts, stalls for various regional cuisines were also set up. The traffic-free pedestrian space provided a secure and vibrant environment and artisans were able to interact directly with customers. Many large exhibitions and craft related festivals and events are held at Dilli Haat fulfilling the main objectives of the initiative. However such efforts were few and far between; there was a glaring paucity of professionally managed marketing initiatives for craft, especially in the context of the extraordinary large numbers of skilled artisans still working in the country. Most NGOs who were in touch with craftspeople and worked for the development of crafts at grass-root levels viewed the idea of 'marketing' with a bit of scepticism. It is likely that they believed that marketing entailed a 'commercial' aspect that was at odds with their objectives. NGOs like Sewa, Dastkar, Dastakari Haat Samiti as well as the Crafts Councils were happy to work on promoting crafts through bazaars and exhibitions usually availing of grants from the government. They were indeed successful in their attempts at linking the rural producers with the urban customer. Such efforts also laid a fertile ground and framework for future developments in the retailing of handicrafts. Amongst the few private organisations that stepped in and invested in marketing the handmade in retail in the initial period was Fabindia. It became known for establishing many benchmarks in how to work in a professional manner with the artisan. Clothing brands like Anokhi and Tulsi also successfully established their retail outlets for designed and hand worked textiles. The Crafts Council of India ( CCI) , an NGO working in this sector since the 60s , entered the retail space for marketing handicrafts in 2005. By then it had become apparent that one of the pressing needs of the sector , that of marketing , required much more than the sporadic attention it was receiving. Along with Delhi Crafts Council, a regional chapter, CCI set up KAMALA, a small retail outlet for crafts in New Delhi dedicated to the memory of its founder Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay. Starting with the interiors, the approach to be taken at KAMALA was clear , it needed to reflect the philosophy of the handcrafted. Therefore natural materials like bamboo, stone and textiles were used throughout the interiors along with simply worked out displays using bamboos. [gallery ids="166793,166794,166804"]

Interiors of KAMALA using natural materials like bamboo

The ambience was designed to offer a harmonious and up-market experience to the customer while buying crafts, the attempt being to ensure that craft is displayed in the best possible manner and in a setting commensurate with its inherent value. As a corollary , the prevalent widespread practise of selling craft at a discount was actively discouraged at KAMALA. Such 'incentives' only served to devalue the handcrafted product. Some of the noteworthy efforts in regenerating traditional crafts that have worked well at KAMALA include bamboo chiks which is a traditional craft of the northern region. It started initially as a design project undertaken by Delhi Crafts Council ( DCC ) intended to introduce new designs into the market to address the steadily dwindling demand for chiks. The project , however, in spite of many efforts like promotional exhibitions continued to be commercial unviable for DCC. Therefore, another attempt was made to revive it now through KAMALA. Proper systems of measurements, quality checks , necessary documentation and most importantly regular interaction and monitoring of the artisan were some of the aspects to which due attention was paid this time. The success of this consistent input which could be carried out at KAMALA with some ease, is evident in the sizeable quantities of chiks currently being processed , they are also being exported. The orders have increased dramatically over the years, so much so that the next generation of chiks makers, who had gone into alternative sources of employment like driving scooters and other menial jobs have once again gone back to the craft and are able to earn a decent living from the orders. As far as innovations are concerned , at KAMALA the artisan himself is always an integral part of the process. His insights are found to be invaluable, reflecting as it does a thorough knowledge of the material coupled with years of experience in dealing with the technicalities of production along with a creative ingenuity suited to his craft. Such a dialogue is also essential to help retain the identity and special features of each craft. Umar Daraz, a gifted kite maker from old Delhi, also in need of work, is an example of such a close collaboration. The idea of creating wrapping paper using his kite making skills was conceived and discussed with him. He came up with startlingly modern designs and colours which became instantly popular, so much so that the range was expanded to include gift bags and notebooks. He was able to introduce several innovative ideas like using ice cream sticks as ties in the gift bag.

Wrapping paper and gift bags made by Umar Daraz, traditional kite maker.

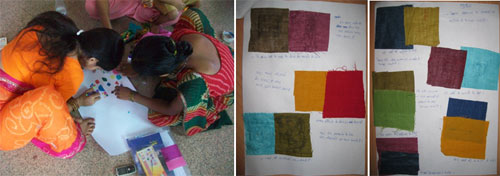

These appliqués are created by Sirali, a non-traditional self-help group of women in Jharkhand who have also trained in design workshops with DCC. Through their work they have been able to interpret and express the modern world around them in a completely authentic way. Suggestions regarding colour schemes and sizes are all that is required for them to supply regular orders through the year.

[gallery ids="166799,166800,166801"]

Appliqué on cushion covers done by Sirali, a self help group from Bihar

There is a section devoted to traditional folk paintings , of which an enormous range is available readily. Interesting frames and ways of hanging are worked out to display them.

Kasuti ,a traditional form of embroidery done on a khadi saree with a new colour range different from the original colours of the embroidery. The designs and techniques remain traditional.

creating wrapping paper using his kite making skills was conceived and discussed with him. He came up with startlingly modern designs and colours which became instantly popular, so much so that the range was expanded to include gift bags and notebooks. He was able to introduce several innovative ideas like using ice cream sticks as ties in the gift bag.

Wrapping paper and gift bags made by Umar Daraz, traditional kite maker.

These appliqués are created by Sirali, a non-traditional self-help group of women in Jharkhand who have also trained in design workshops with DCC. Through their work they have been able to interpret and express the modern world around them in a completely authentic way. Suggestions regarding colour schemes and sizes are all that is required for them to supply regular orders through the year.

[gallery ids="166799,166800,166801"]

Appliqué on cushion covers done by Sirali, a self help group from Bihar

There is a section devoted to traditional folk paintings , of which an enormous range is available readily. Interesting frames and ways of hanging are worked out to display them.

Kasuti ,a traditional form of embroidery done on a khadi saree with a new colour range different from the original colours of the embroidery. The designs and techniques remain traditional.

embroidery done on a khadi saree

Papier Mache containers made by Chakradhar, a papier mache artisan from Bihar. These are painted in graphic designs by his daughter . The suggestion of using colour sparsely was made to him and has made a difference to the visual appeal of the product.

embroidery done on a khadi saree

Papier Mache containers made by Chakradhar, a papier mache artisan from Bihar. These are painted in graphic designs by his daughter . The suggestion of using colour sparsely was made to him and has made a difference to the visual appeal of the product.

Papier Mache containers made by Chakradhar of Bihar

It is gratifying to note how quickly most of the artisans supported by KAMALA hav e become adept in the use of modern technology. They have been able to bridge the gap of long distances by communicating using the latest technology and 'apps'. This ease of communication has greatly facilitated the sourcing and supply of products from distant corners of the country , this in turn has benefitted the artisan by saving both time and money spent in unnecessary travels. Each and every time, the artisan has proved to be pro-active and forthcoming in his dealings once a basic level of trust has been established.

Over a short period KAMALA has become self sufficient and does not need any subsidy to keep it running. Besides the commitment and voluntary services of the team of members responsible for running it , all operational and infrastructural costs are covered from the sales and all profits are ploughed back into the project. The fact that a single outlet of about 1600 square feet takes care of the needs of almost a thousand artisans speaks volumes for the potential for growth of such participatory ventures.

KAMALA is a retail space with a difference; it is run by two organisations with a stated objective of supporting and sustaining artisans , nevertheless it is important to look at the value of providing such a service. Although essential, economics is perhaps only one aspect of the endeavour. Keeping the artisan at the centre of this initiative, KAMALA is able to provide an important and much needed interface between a new market and the artisan who often feels he is working in isolation but is eventually able, with some help, to make sense of the enormously expanded global world and his own special place in it.

The world connected with handcrafts is going through unsettling times thus affecting the second largest community in the country in terms of employment . It is common knowledge that everyday many hand skills are disappearing , many more are being steadily decontextualised and de-rooted. It is therefore critically important to look at creating new and enabling environments for crafts to survive. It is not a matter of aesthetics or profits, what is at stake here is the potential for harnessing large numbers of human beings in occupations that allow them to lead lives of dignity and self worth. It is important to realise that many of these traditional occupations using hand skills are not only repositories of cultural identities but are also investments into an ecologically sound future. All currents trends predict with certainty that 'handmade' is going to become the luxury brand of the future. An awareness of such an outcome and India's central place in it should play an important role in shaping the future map of handicrafts and the many hands that make such a future possible.

First published in Varta.

e become adept in the use of modern technology. They have been able to bridge the gap of long distances by communicating using the latest technology and 'apps'. This ease of communication has greatly facilitated the sourcing and supply of products from distant corners of the country , this in turn has benefitted the artisan by saving both time and money spent in unnecessary travels. Each and every time, the artisan has proved to be pro-active and forthcoming in his dealings once a basic level of trust has been established.

Over a short period KAMALA has become self sufficient and does not need any subsidy to keep it running. Besides the commitment and voluntary services of the team of members responsible for running it , all operational and infrastructural costs are covered from the sales and all profits are ploughed back into the project. The fact that a single outlet of about 1600 square feet takes care of the needs of almost a thousand artisans speaks volumes for the potential for growth of such participatory ventures.

KAMALA is a retail space with a difference; it is run by two organisations with a stated objective of supporting and sustaining artisans , nevertheless it is important to look at the value of providing such a service. Although essential, economics is perhaps only one aspect of the endeavour. Keeping the artisan at the centre of this initiative, KAMALA is able to provide an important and much needed interface between a new market and the artisan who often feels he is working in isolation but is eventually able, with some help, to make sense of the enormously expanded global world and his own special place in it.

The world connected with handcrafts is going through unsettling times thus affecting the second largest community in the country in terms of employment . It is common knowledge that everyday many hand skills are disappearing , many more are being steadily decontextualised and de-rooted. It is therefore critically important to look at creating new and enabling environments for crafts to survive. It is not a matter of aesthetics or profits, what is at stake here is the potential for harnessing large numbers of human beings in occupations that allow them to lead lives of dignity and self worth. It is important to realise that many of these traditional occupations using hand skills are not only repositories of cultural identities but are also investments into an ecologically sound future. All currents trends predict with certainty that 'handmade' is going to become the luxury brand of the future. An awareness of such an outcome and India's central place in it should play an important role in shaping the future map of handicrafts and the many hands that make such a future possible.

First published in Varta.

Why are craftspeople absent in the country's trade policy space?I was asked this question while working on a report that analyses in some detail the effects of trade and globalisation on 'human development' in South East Asian countries. The report discusses at length how the lives of food growers, fisher folk, textile and garment producers - even workers in tourism and BPOs (business process outsourcing) - are being affected by the increased opening up of the South and South East Asian countries in the last decade. It has policy pointers on how developing countries can harness trade to improve the lot of these workers, and raise their human development quotient. The 'human development lens' of the report views the effects of trade on the productivity and empowerment of workers, how sustainable the process has been, and whether income disparities have increased as a result. These are the very issues with which workers in the crafts have to contend.No Space in the Policy SpaceCraftspeople had no 'voice' in the report. And little - if any - representation in the trade negotiations that our government officials are involved with at the World Trade Orgainsation (WTO - the body that determines the rules for almost 90% of world trade). This is surprising when we consider the numbers involved. Almost 10 million people work in the area of crafts, most of them are poor, and many of them are women - all of which make them ideal candidates for government programmes that typically target the 'deprived' sections. If the government needs other reasons for its intervention, one only has to look at the wide-ranging effects of opening up of trade on Indian craftspeople's hold on the domestic market. The influx of cheap mass-produced 'traditional' weaves from China (Kanchipuram saris, Kuchhi embroidery and now Benares brocades) have had disastrous consequences for our weavers - some of whom have committed suicide from financial distress. This diwali the flood of Chinese-made murtis (idols) must have had serious consequences for the artisans and small-scale enterprises who have traditionally met this market demand.Needing the face and 'hand' of the governmentCrafts had no space in the original framework of the WTO, because the agenda was largely determined by industrialized countries and included areas they considered important -agriculture, fisheries, and so on. As developing countries have woken up to the dire consequences of some of the original WTO decisions, they have taken a more pro-active role in negotiations. They are now promoting new areas and protecting policy space that are more in keeping with their own countries' needs, such as greater access to jobs in developed countries by their workers; and a reduction in agricultural subsidies in the West. Crafts however are still not on the new trade agenda of our negotiators. At a recent stakeholders' consultation in the capital different groups and communities had been invited to make presentations to commerce ministry officials. The expectation was that these concerns would be incorporated into India's position at the WTO Ministerial in Hong Kong in mid-December. There were representations from diverse farmers groups, environmentalists, even the trained nurses association, but only one person from the crafts world (NEED, a Lucknow-based organization working to promote grass-roots entrepreneurship, which raised valid concerns on handicrafts in the trade arena). As I see it, in the face of ever-increasing globalisation our domestic craftspeople need help on two fronts: managing their domestic markets and promoting craft exports. Both of these will need a pro-active government. This summer, the US placed an embargo on Chinese garments that had been flooding their markets. While I am not advocating such an extreme, short-term step, we need to promote a pride in our traditional crafts, and create awareness of the threats to traditional knowledge. Maybe it's time to revive the old khadi generation slogan, Be Indian buy Indian, for a new generation of consumers, schoolchildren, and even retailers. The beauty of the uneven textures of a handmade object or the giveaway irregularities in our traditional silk saris have to be celebrated over the bland aesthetics of the mass-produced imitation. On export markets, the good news is that contrary to popular perception, Indian crafts exports have increased fairly dramatically since the early 1990s: the proportion of craft output (excluding handlooms and jewellery) being exported has gone from 22% to almost 70% today. This wave has been fuelled by an increase in global tourism, and the growing trend in niche markets in reaction to the "Walmartization" of the marketplace. Indian craft exports, however, today are only the tip of the iceberg of the country's potential. There are vast markets waiting for our craft producers if only we could tackle the constraints in the sector - raw material scarcity, dealing with remote markets, access to credit, infrastructure bottlenecks, bureaucratic red tape, to name a few, these have been well-documented in the studies on this area. One of the most important constraints is proper marketing of our crafts abroad. Thus both forms of support to the crafts call for active market campaigning by the government. Whether marketing 'Handmade with Pride in India' abroad or within our own markets, the scale of the task and diversity of crafts and their markets need the face - and 'hand' of the government. Trade can improve poor people's livelihoods; the Chinese experience has clearly demonstrated this. And rather than wring our hands over the death of our crafts from globalisation, we should be able to manage trade negotiations and marketing policy to open up market opportunities for Indian craftspeople that will truly improve their livelihoods. Who knows, for the Chinese Lantern Festival next year, our paper makers could be flooding Chinese markets with paper lanterns made in India. |

|

As the first article of the year, this was to have been a positive one – focusing on headway that had been made by the government in tackling some of the problems faced by craftspeople. Progress could be measured either by measuring outcomes – in this case, the living standards of the target populations - or by looking at the inputs - government programs aimed at improving the lot of craftspeople. In both cases I drew a blank. Improvements or changes in the living standards of crafts people and artisans cannot be commented on for the simple reason that there are no current data relating to this group – so no comparisons can be made. Nothing can be presented to balance the dismaying news about the distress faced by some of the craftspeople who find they can no longer support their families in the face of competition. There are scattered success stories of increasing individual’s or some SHGs’ (Self Help Groups) access to markets, or achieving self-sufficiency. But, as a whole, there is no way we can tell if income or employment levels have increased among craftspeople – even as the reduction in poverty levels in the country over the past decade have meticulously been measured, debated over and well documented. The most recent enumeration of ‘handicraft artisans’ was carried out in 1995-96 by the NCAER (National Council for Applied Economics Research), but by its own admission this was limited to the ‘known craft concentration pockets’ in the country and excluded several crafts such as agarbattis and gold jewelry. Given the heterogeneity of the sector, and the issues of definition and overlap with other areas, this is a creditable beginning The information is now over a decade old, and was to be updated by the NSSO (National Sample Survey Organisation), in its next round. But this has been put on hold once again. This brings us to an important issue not just from the point of view of measuring progress, but of policy making. A reliable database is fundamental to micro-level planning in any sector. And handicrafts is no exception. To be effective, well-targeted, and not another colossal waste of funds, policies need to first be grounded in numbers. Other inputs matter, but they come later. A comprehensive enumeration of the crafts sector is the first step to revealing specific problems and issues in each sub-sector, the extent of these problems, which areas need to be targeted first, and so on. At present, instead of being based on n a rigorous framework, the country’s planning for the crafts sector relies on the varying interest and inputs of NGOs and other bodies, and on the fluctuating interests of exporters. Well-meaning as these may be, they may not even touch on the worst-off within the community. The Planning Commission is the government body that determines priorities and allots funds to different sectors for improving living standards, and increasing production and employment. It acknowledges the powerful employment effects of the handicrafts sector and its foreign exchange generation potential through exports. But its Tenth Plan (2002-07) had to use data on handicraft exports to derive production and employment figures, and thus to allot funds for different projects “as a comprehensive database for handicrafts is not available.” Its stated objectives are primarily aimed at improving exports from this sector, while welfare of crafts people appears to be secondary or even tertiary (after the “preservation of cultural heritage”) to the exercise. Inputs into the sector – the central government schemes - were shrouded in mystery. A ‘talk’ with one of the officials in the Village and Small Industries Division of the Planning Commission revealed nothing. Apart from the size of the current Annual Plan (Rs 150 crore) an attempt to find out which schemes were successful or where policy could be directed, was abortive. The website of the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) listed some of the many schemes available for craftspeople, but the language is obtuse, and probably far beyond the reach of the target audience. While the right to information is an unalienable right for all of us, the information itself is not to be had. We are still in the dark about how craftspeople – a huge employment force in the country – are doing. |

|

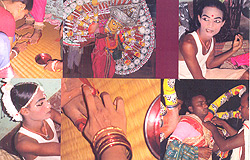

A little-known survey of the tourist-centric regions of Kerala and Rajasthan* shows that tourism has an enormous impact on the incomes and livelihoods of artisans in the region. Incomes of ‘folk artists’ for example are four times higher during tourist seasons compared to their off-season incomes; higher earnings of all artisans from their proximity to tourist centres enables them to improve their quality of life. The multiplier effects of tourism are well known: that money spent by a tourist has a cascading effect on incomes and employment through an economy, because tourism is strongly linked to so many other areas of activity. This borne out by the survey mentioned above which shows, for example, that 96 per cent of the income of the artisans surveyed in Kerala and 90 per cent in Rajasthan is derived from tourist spending. The flip side of the scenario is of course that during a nuclear blast year (such as 1998) or a plague year, tourism-dependent craftspeople suffer badly. Artisans clearly stand to gain from tourism, but this important avenue for advancement has almost completely been ignored in India. Crafts products can be found in ‘cottage industries’ emporia, but how many of the local crafts can you find next to a tourist spot, which is where visitors often spontaneously buy mementos? After spending a day or more marvelling at the craftsmanship of the 14th and 15th century sculptors of the sprawling Vijaynagar ruins at Hampi, there is nowhere you can buy something from their present-day counterparts. The best that you can find at Delhi’s Qutab Minar, or the Mammalapuram (Mahabalipuram) temple complex outside Chennai is a string of indifferent postcards, mostly of Bollywood stars. In many of the major tourist sites, this ‘local souvenir’ space has been taken up by enterprising marketers from a few states. How many visitors to Goa have bought – or even seen - any of the local crafts products based on the culture and materials of the region? We may be forgiven for thinking that Kashmiri shawls or Tibetan jewelry, so ubiquitously available on the beaches, are the local craft. This is the good news, though, as at least craftspeople somewhere are benefiting from tourism expenditure. But there are at least two negative effects from this cross-regional crafts supply: one is that they tend to ‘crowd out’ local craftspeople who may have not yet developed the skills to access their tourist markets; second, in economic terms, money spent on out-of-region crafts is a leakage from the region - as it does not directly improve the quality of life of local craftspeople – and this limits the extent of second and subsequent effects on other workers in the region. Local crafts thus need to be made more visible and accessible to tourists. Many recommendations exist on how this can best be done, and I add my own: make available good quality local products, crafts, even processed foods at airports and train stations, or even at checkpoints at state boundaries (such as Hill Stations). There is an even more important role for craftspeople in today’s tourism, as a counter-pose to the devastating effects of mass tourism on the cultures and environment of popular destinations: pressure from travelers in search of nothing more than a warm place in the sun have stripped beaches in several parts of Thailand, Bali, and Goa, almost completely of their unique cultural character. In reaction, there is a growing trend towards more responsible travel such as community-based tourism (CBT), in which local communities are at the centre of the travel experience. It varies from region to region, but can incorporate some of these elements: living with local communities, eating and cooking with them, learning how to make their handicrafts, and being part of their festivals and even agricultural activities. We now have several CBT projects across the country, which have given rural-based crafts people a market, diversified their job opportunities, and encouraged them to revive and preserve their indigenous traditions – crafts, festivals, dances, and even medical practices. The artisan community in Hodka village in Gujarat encourages visitors who stay in their village to learn their traditional crafts (www.hodka.in); a similar project in the village of Khedi outside Gangtok in Sikkim has led to careful preservation and restoration of local Bhutia homes, cooking utensils, and other traditional everyday implements, and given a boost to the local broom-making craft. Even the most recent union budget recognized the close links between crafts and tourism as it planned to “identify 50 villages with core competency in handicrafts, handlooms and culture close to existing destinations and circuits, and develop them for enhancing tourists’ experience.” There are obvious negatives to relying solely or largely on any one market. These need to be addressed to protect craftspeople from a sudden falling off in demand, but at the same time we need to fully develop our local souvenir-crafts, before the vacuum is filled by products that are made anywhere but in India. * ‘Socio-economic Impact of Tourism on Folk Artists and Artisans of Kerala and Rajasthan,’ Tourism Statistics 2003, Department of Tourism |

Issue #003, Autumn, 2019 ISSN: 2581- 9410

The Victoria Terminus, erstwhile Headquarter of the GIPR – Grand Indian Peninsular Railway - is now renamed Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus. In 1887, it opened just in time for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, after taking 10 years to build. Preparations for the royal celebrations in London were then on, with plans for eminent personalities of the time to be in attendance –including the Maharajas of Gondal, Coochbehar, Kutch and Indore. Meanwhile, artists, sculptors and builders from regions around Mumbai were embedding the evidences of their charming handiwork into the Gothic- Venetian – Indian – Islamic all too wondrous mix that would become the facade of the Terminus.

“Much too magnificient for a bustling crowd of railway passengers”, was the prim judgement of Vicereine Lady Dufferin. (1889; Railways of the Raj, by Satow and Desmond). It was then that the building was gaining in fame and prominence. Erstwhile Bombay Fortifications, linking Khandesh and Berar via the GIP Railways, were important to export cotton, spices, opium sugar and silk from Bori Bunder port to the consumers in England. The criticism of the Vicereine was perhaps lost in the symbolism of the Terminus that was the latest and most important part of the Bombay Fort, and its offering of strategic rail connectivity between land and sea.

Picture 1: Artists impression of Terminus façade 19th Century drawing

Picture 2: An existing sculpture from the Terminus interior, of a lion with its paws gripped on the armorial bearings of the GIP railway

Like icing on a cake, each detail of the facade embellishesthe outside. Then, the eye must carefully focus and pick out each feature, to analyse the elements that make up the whole.

Carved Stone decorations

The JJ School of Arts, established in 1857, had Italian sculptor Francisco teaching and training hordes of artists, some of whom were employed to make the decorative carvings for the Terminus. Along with the distinctly Gothic gargoyles, detailed Indian fauna is represented in the carvings of tigers and lions, owls, monkeys, a stately ramshead, squirrels - all cleverly hiding the sharper corners, and the ventilation and rainwater runoff openings in the exterior.

Picture 3: Elaborately detailed Peacocks abound, wings folded or flared, and they are a favoured motif above windows.

Larger openings cut out in stone are designed as staid four-petal floral motifs. Creepers and flowers then burst out exuberantly along the cornices, tops of pillars and awnings. Stone flower jaalis follow the arched outline and embellish every architectural detailing elementon the inside as well as out.

Picture 4: Variations in windows, cornices, jaalis and railings make the façade intricate yet composite part of diverse cultural motifs

Glazed tiles

The original hand glazed floor tiles had “GIP” inscribed on them, but gave way to the ravages of time. They were in colours mirroring the yellow, red, blue and gold featured in building materials used throughout the building.

Western design and Indian concepts

CSMT is the physical representation of the meeting of two cultures. The British conceptualised and planned the architecture of the city to represent dramatically the new ideas of progress and modernity. British architects worked with Indian craftsmen to include Indian architectural tradition and idioms, in the process forging a new style unique to Bombay.

Picture 5: Medallions in the façade represent the sculptured busts of financers, designers and architects of the Terminus.

Brass and Wrought Iron Work

Floral brass work combined in wrought iron grilles adorns every railing of the many staircases inside the building. Sturdy iron frames topped with forbidding spikes, permit the creative flourishes of spirals, wreaths and flowers to burst across the grid of the many gated barriers of wrought iron.

Picture 6: Metal railings on the grand central staircase

The embodiment of Artistic Sensibility in design of the Terminus

The historic context of the GIP Railway beginnings are important to understand how artistic sensibilities got embodied in the Terminus design. This was a Crown initiative, celebrating India as a colony and starting passenger railway services in the cotton rich Deccan region.

Stained Glass Windows in the upper dome of the Terminus have the GIP Railway logo and coat of arms, which evocatively states “ARTE NON ENSE” or “By ART, Not by the SWORD”. Perhaps this best captures the continuing artistic statement of supporting local arts, crafts, motifs and decorations, even if they were severely contained in the gridlock of sturdy stone, wood and iron framework. The site of the Bori Bunder station itself is that of the Mumba Devi temple that gave the city its ethnic name.

Pictures 7 and 8: GIP logo and painted patternsand gold flecked decor draw the eye upwards to admire the height of the interior dome.

Pictures 9 and 10: Gilded ceilings and massive marble pillars emphasise grandeur and scale. Polished imported Italian marble in blues and reds introduces colour in the interior

Teak wood doors and furniture

Woodworkers were not to be left behind. Massive original teak doors are mostly intact but needed restoration. They have half a meter long brass hinges and decorations, and panels with wood carved jaalis. The furniture, grandfather clocks and wood rafters have the carved GIP logo, and lasting strength and workmanship.

Picture 11: Wood doors and elegant interiors

The massive 10 year long original build of the CSMT, and its recent restoration by conservation architects, demonstrate the combined efforts of architects, builders, designers and native workers in a way few buildings can stake claim to. Justifiably a UNESCO recognised World Heritage site, CSMT is to be treasured and admired as much as the “lady of progress” statue that stands atop it.

Picture 12: Statue of the “Lady of Progress”

Pictures 13 and 14: Restoration and Conservation

I am fortunate to have been involved in the setting up of two significant new Institutions that are focused on the creation of trained human resources and strategies for the Crafts Sector in India. These are the Indian Institute of Crafts and Design, Jaipur set up in the mid ninety’s and the Bamboo and Cane Development Institute, Agartala. Both are informed by the vast body of work carried out at the National Institute of Design over the past forty years in our collective attempts to understand the role of crafts in the Indian context as a major resource for both design education and for the economic and social development of India as a whole. During the various deliberations that led up to the establishment of these new initiatives a number of insights emerged on the role of the crafts in India and the need for expanding the involvement of new players in the strengthening of the sector and expanding it in many new directions through design and strategic interventions. Some of these concepts were captured and formed the basis of our strategic initiatives for new education of designers and craftspersons to meet the challenges ahead.

The problems of the craft sector are manifold and it also represents a major area of opportunity for development planning in the scenario of the scanty financial resources available in our economy for such a widespread development initiative. Crafts are a great source of employment in our villages and towns.

The existing handicrafts sector has massive resources of fine skills and technical know-how which in some cases are products of centuries of evolution and are still active in various parts around the country in the form of traditional wisdom embedded in the fabric of our culture. The handicrafts sector is therefore an enormous source of employment, particularly self-employment, for a vast number of people who are otherwise involved in agricultural activities, represents an opportunity that cannot be ignored. In many areas, production of handicrafts is the sole sources of income for the communities for whom it is the only source of sustenance.

Traditionally, such handicrafts producers deal with local markets with which they had direct links through contact with the consumer, be it a bazaar buyer or a local patron. However, with the vast economic changes that have been taking place, most of these crafts are facing a very bleak scenario by being marginalised by a variety of industrial products, squeezing traditional markets or the margins generated by their endeavour.

CRAFTS IN A NEW LIGHTIt should be understood here that the term Crafts is used in a very specific sense to mean those activities that deal with the conversion of specific materials into products, using primarily hand skills with simple tools and employing the local traditional wisdom of craft processes. Such activities usually form a core economic activity of a community of people called craftsmen. The emphasis here is definitely not on Art although a very high level aesthetic sensibility forms an inherent part of our definition of craft along with a host of other factors that constitute the matrix. This being an economic activity that is exposed and influenced by all the competitive pressures of a dynamically shifting marketplace, our new generation of craftsmen would necessarily have to depend increasingly on high quality market intelligence and strategies design to be pro-active, particularly while dealing with remote and export markets. The generally low level of education that is today available to the average craftsmen adversely affects their ability and responsiveness to such changing needs. It is further restricted by the acute absence of capital and the lack of a free flow of knowledge about the competitive shifts that are constantly taking place in this information centered world. While the Know-How (How-to-make-things - knowledge & skills) exists abundantly in the crafts sector there is a severe shortfall in the Know-What (what-to-make - strategies & designs) that curtails the ability of crafts communities to survive intense competition or, better still, develop value-added solutions in the complex economic and social matrix in which they exist Besides the continued and sustained development of the traditional crafts and their traditional stake holders, such as hereditary craftsmen and their children, we need to look at a much broader catchments of human resources that can revitalize the whole crafts movement in India and in the process help build a competent and creative India of the future. Much of our youth and the students of the modern education systems miss the critical values of crafts that were imparted in the traditional societies in India in the past in our villages. Today the so-called modern education has reached our villages too without any re-appraisal of the relevance of the inputs and the content and capability that they impart to our young learners. The crafts sector by its very nature is heterogeneous, both from the point of view of the material and technological processes used in each of the crafts as well as in the situations in which the craft communities work in different regions of the state or the country. This implies that individuals working in this sector would necessarily have to be flexible and broad-based in their approach and be able to understand the large variety of technologies and have the competence to work in a generalist capacity A flexible outlook and a regional focus could give us both variety and relevance to local context in bringing the new crafts capabilities to our young learners as an integral part of their broader learning to cope with the new age ahead.Crafts training with expanded mandateWhile the programme proposed and implemented at the IICD, Jaipur were focused on the creation of young designers for the crafts sector our efforts at the BCDI, Agartala was on the creation of a new class of crafts-persons who would also act as entrepreneurs in the remote villages of our country, particularly focused on the development of the Northeastern sector. The curriculum that was designed from ground up looked at the needs and capabilities of the young candidates who were expected to join the programme offered there. We were fortunate to have had the opportunity to test our curriculum with three batches of craftsmen trainees, most of whom were women, and the results are indeed heartening. We now need to look further a field and see how crafts education can be introduced to the regular school system and the experiments done in the United Kingdom through the introduction of design and technology at the school level may through some light on directions for explorations in India. Besides learning about the materials and technologies relating to particular crafts the students in our schools could also be exposed to critical project based situations as well as be placed in direct contact with craftsperson’s and other individuals working in the region through which they would gain insights into the human resource needs and aspirations of the handicrafts sector within the local context. Such an exposure carried out under the guidance of specially sensitized faculty, perhaps local craftsmen, would help develop the broad-based competence that is required as well as instill in the student a capacity to face complex problems and develop strategies for the resolution of these problems. I do believe that crafts education that goes well beyond mere hobby classes or vague introduction to the fine arts at the middle and high school levels can and needs to be innovated to make India a creative and potent force that it was when handicrafts was the basis for our local and export economy in the past. I do hope that we move towards such educational innovations that can indeed make a creative India of the future. Paper prepared for the seminar organized by the Crafts Council of India from 4th to 6th April 2003 at Bangalore |

| 1: Areas of Focus | |

| Mainstream | Peripheral |

| Primary Education—Village School Secondary Education—High SchoolHigher Education—University / Institutions | Vocational Education— ITI / Guilds Adult Education—LiteracyDistance Education—Qualification |

| 2: Tendencies and Leanings | |

| Bias | Neglects |

| Towards White Collar Jobs Literacy, Numeracy Focus Explicit Knowledge Domains | of Visuality—Aesthetic skillsof Creativity—Imaginative skills of Sensitivity—Sensory skills Tacit Knowledge Domains |

| 3: Anticipated Results | |

| Produces | Neglects |

| Intellectual CompetenceVerbal Competence Numerical Competence… | Material Competence Action CompetenceSensory Competence… |

| 4: Methods and Orientation | |

| Belief in | Overlooks |

| Specialization StandardizationSpecifications… | Generalist attitudes ExperimentationExperiencing from the field... |

| 5: Ideological Underpinnings | |

| Bets on | Neglects |

| Science methods Technology attitudesManagement case studies... | Design and innovation Craft and skillsLearning by doing approaches... |

| 1: Focus of Government Policy | |

| Focus on hard statistics | Underplays the softer aspects |

| Craftsman and povertyEmployment generation Commerce... | Craftsmanship Spirit of enterpriseMeaning of production in society... |

| 2: Desired Orientation for the Crafts | |

| Build capability in | Offer opportunities in |

| Innovation using local crafts Experimentation with local skillsRisk taking and entrepreneurship... | Competence and variety building Sensory development and experienceCreative avenues for self fulfilment |

| 3: Untapped Opportunities in Crafts sector | |

| Using our crafts development resource | In order to provide |

| As a skill and teaching resource As a tacit knowledge poolAs a traditional wisdom resource... | Localization of education opportunities Inculcate experimentation and innovation Meaningful projects from the field...Within mainstream education |

| 4: Parameters for Effecting Change | |

| Needs Investment in | With emphasis on |

| Design and Crafts infrastructure Innovation of curriculum and assignments Infrastructure for material exploration... | Connecting craftsmen to schools Project based integrated design learning Rich local content from the fieldResearch supported competence... |

| 1: Core attributes and values thatwould inform this movement | |

| We must therefore nurture | |

| Craftsmanship = Quality | Sportsmanship = Ethics |

| 2: The Proposed Models for Change | |

| Innovative Approaches | Innovate Institutes and experiments |

| Design for Craftsmen and Citizens Design in General Education Craftsmen as Teachers and Mentors... | IICD, Jaipur (Case 1) BCDI, Agartala (Case 2)Craft enabled Model Schools (proposal for school level)Crafts informed University and Crafts Shala ... (proposal for higher education) |

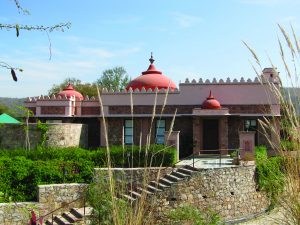

Issue #002, Winter, 2019 ISSN: 2581- 9410 Across the globe, craft has oftenbeen associated to small scale 'products' and 'objects'; one misses out the enormity of craft in the traditional and vernacular architectural structures.In India, the craft landscape comprises of numerous types of applications which range from vernacular objects of daily use that are made from locally sourced materials to the celebrated objects of symbolic value used on special occasions either for personal or religious use. The built landscape of India also depicts the vastnessof craft productions at various scales. The legacies of craft traditions that shaped Indian architecture since ages are being consistently questioned and are subject to validity in our contemporary and modern environment. Space Making Crafts which also form an inherent tradition in our country are being manifested in diverse ways with multiple overlays of culture, tradition, design and many external forces. The country stands in the middle of a multi-faceted architectural landscape where there are numerous ideas shaping the building industry. It projects a mixed vision that blurs down to a state of absence of a cultural identity. While many buildings portray a departure from the traditional architecture; others have been integrating crafts in the built environment claiming an Indian identity in the built landscape worldwide. An attempt to understand the complexity of crafts and its manifestation in the built environment of India is made through this paper. It discusses the concept of Space Making Crafts in the initial part. It also elaborates on how space making crafts lend a unique identity to the nation. In the latter part, the current status of Space Making Crafts is discussed along with the various approaches towards craft design innovation that are lending an Indian Identity to Interior Architecture practices of India.

CONCEPT OF SPACE MAKING CRAFTS

There is a difference between a craft being applied to an object and a craft applied to a space. The former is applied on a smaller scale and allows movement, while the latter is completely integrated and fixed to a particular space. Space Making Crafts are not mobile (in most cases), as they are an integral part of the space and cannot be separated from that particular environment. The desire to be more meaningful in expression and communication increases manifold in Space Making Crafts, as in a particular space the role of crafts has to fit within the context, construction systems and the environment of that place. The Space making crafts are the various tangible and intangible expressions lent to an architectural space by a skilled craftsperson(s) or artisans, using various materials, processes, tools and techniques which modify or add to its cultural aesthetic. Space making crafts includes a wide plethora of crafts that are directly or indirectly related to a built environment ranging from wall decorations, furniture, products, interior-architecture elements to structural elements and processes of building; all of which essentially involve the active participation of a craftsperson(s). These skills or techniques that make up a three dimensional space are indigenous in origin but may or may not be so in expression and execution. Space Making Crafts comprise a vast array of crafts including both the hard and soft materials and the techniques used. They are not only confined to the techniques of construction or the skill of creating the elements. They engage sensorially, spiritually, physically as well as psychically. Figure 01: Division of various space making crafts on the basis of material, 2011

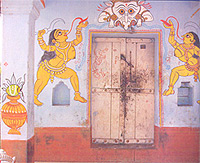

Space Making Crafts are an integral part of a culture of the place and they have been also a portrayal of a regional identity of a particular place with multiple associations of society, culture, religion etc. A singlespace making craft varying in expression, gave a uniqueness from the diversity of expressions, iconography, folklore, living patterns and myths and beliefs which varied from one region to other. Most appropriate examples of this would be paintings, frescoes and murals from different regions.

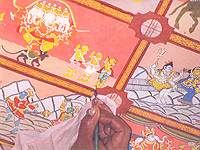

With distinct styles of ornamentation and surface decorations, the space making crafts are a storehouse of motifs, patterns, symbolic representations which have been constantly evolving throughout the history. Such motifs and patterns are often absorbed by a culture and then are disseminated across different kinds of media and are sometimes transferred to different kind of materials too. For example, the transfer of a motif from stone to wood, from handloom weaving to block printing, from the metal work to fabrics; and this has brought a unique amalgamation of the material and expansions of tool.

Figure 01: Division of various space making crafts on the basis of material, 2011

Space Making Crafts are an integral part of a culture of the place and they have been also a portrayal of a regional identity of a particular place with multiple associations of society, culture, religion etc. A singlespace making craft varying in expression, gave a uniqueness from the diversity of expressions, iconography, folklore, living patterns and myths and beliefs which varied from one region to other. Most appropriate examples of this would be paintings, frescoes and murals from different regions.

With distinct styles of ornamentation and surface decorations, the space making crafts are a storehouse of motifs, patterns, symbolic representations which have been constantly evolving throughout the history. Such motifs and patterns are often absorbed by a culture and then are disseminated across different kinds of media and are sometimes transferred to different kind of materials too. For example, the transfer of a motif from stone to wood, from handloom weaving to block printing, from the metal work to fabrics; and this has brought a unique amalgamation of the material and expansions of tool.

SPACE MAKING CRAFTS IN TRADITIONAL BUILT ENVIRONMENT OF INDIA

The vernacular structures and the traditional buildings in various parts of India show the integrity and the involvement of crafts in the built environment. There was no formalized methods of making, neither was a presence of a trained professional to help with the technical issues. They were constructed with the systems of making mentioned in the scriptures and ancient literature texts and with the skills of a craftsperson. The house forms of the desert areas, especially the bhunga structures in few parts of Gujarat and Rajasthan are one of the best examples of such built forms. Circular houses made of mud and roofed with thatch: these materials being highly suited the hostile desert environment. Also the clustering of huts, the arrangement of various open, semi-open and closed spaces was a reflection of their lifestyles. There was an involvement of craft in every element of the spaces thus created. Also as the users of the space were makers here, they added personalized creativity to the spaces in form of expressions which often carried a symbolic meaning implying auspiciousness and good fortune. Figure 02: Bhunga Houses in Gujarat, 2011

Space Making Crafts added a character to the otherwise harsh and plainer life. It brought associations which were not merely related directly to the built form but also to a specific region, as the wooden constructions associates to the craft of making wooden houses in Kerala where they use the wood extensively. In Kerala the detailing of the wood craft is so immaculate that the wood has sustained till date.

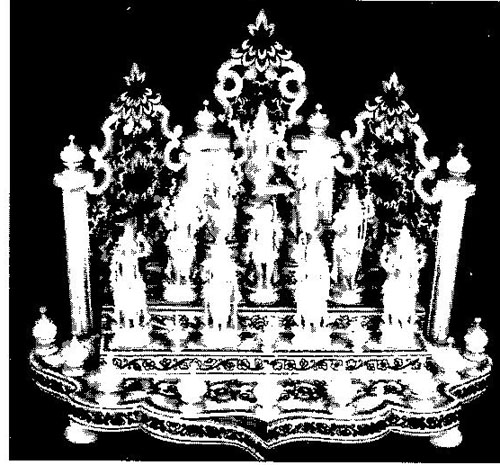

The city palace in Udaipur is one of the prominent examples that showcase different extents of integration of crafts within the built environment with diverse approaches. It induces a sense of spatial quality to the built form. The presence of courtyards and pavilions indicate a spatial organization with reference of the climate of the region. The crafts have been also explored in making of balconies and jharokhas. This palace shows extensive use of crafts associated with glass and mirror work.

Another exclusive example of integration of crafts into the built form is the Adalaj step well located near Ahmedabad,where the stone craft is explored to its full potential which guides the form and massing, the scale and proportion, the space making elements and also the surface decoration. Here the integration goes beyond merely visual impactbut is also associated with various intangible factors. Apart from having detailed ornamentation on various surfaces, here craft helps in giving a spatial quality to the structure.

Figure 02: Bhunga Houses in Gujarat, 2011

Space Making Crafts added a character to the otherwise harsh and plainer life. It brought associations which were not merely related directly to the built form but also to a specific region, as the wooden constructions associates to the craft of making wooden houses in Kerala where they use the wood extensively. In Kerala the detailing of the wood craft is so immaculate that the wood has sustained till date.