JOURNAL ARCHIVE

|

Visiting Northern Italy gave me a chance to get a feel of a countryside that has gone through cycles of industrial change since at least the 1600s. The Eastern part, particularly the Marche region is a perfect example of sociologist Charles Tilly's observation that industrialization is not a linear process "…a straight-line model of industrialization is not merely inaccurate in itself; it leads to faulty, costly deductions" he says. It is wrong to assume that "industrialization follows a straight line from agriculture to handicraft to full-scale industry, with handicraft a weak anticipation of full-scale industry". In this region both craft and mass-production seem to have had their glory days and their bleak stretches, with craft production of leather goods and textiles bringing some prosperity after a period of industrial decline in the early 20th century. I was in Pavia to lecture students of a course on Co-operation and Development at the University of Pavia. Pavia itself, an example of the way in which in Italy the past is part of the present through its lovingly preserved architecture and spaces, is a delight. Pavia is part of the province of Lombardy near the great industrial capital of Milan. Italy had seen the rise and fall of the woollen industry during the seventeenth century. At the beginning of that century, according to Carlo M Cipollo, this region was one of the most industrially advanced in Western Europe, but by its end, Italy had become an 'economically depressed and backward area'. Another industrial cycle began two hundred years later: "Milan's economic success was founded at the end of the 19th century", says an internet site "when the metal factories and the rubber industries moved in, replacing agriculture and mercantile trading as the city's main sources of income". Before this visit I had been to Italy as a tourist, admired the grandeur of Rome, steeped myself in the 'cinquecento', the sublime 16th century of Italian painting, and in the Tuscan countryside, which is the background for those early paintings. This time, travelling with Alessandra L'Abate, I glimpsed another Italy, of artisans, 'fair trade', the peace movement, and a hospitality network. At an artisan fair in Florence in the grounds of the beautiful Palazzo Corsini in whose formal gardens the fair is held each year, we find Alessandra's basket maker friend Giotto Scaramelli weaving baskets and holding a class. "I learnt from my father when every farmer used to make his own baskets" he says. Enzo Sottili has dropped by to visit. He heads an artisans' organization demanding the right to sell their own work on the street: "In the 1950s there was a revolution in peoples' heads. Before that every household had a craft. At that time peoples' attitude changed to 'why should I make anything by hand when it is cheaper by machine'. Now crafts are also using machines and real craft has died". It appears to me that the basket makers and a family of bronze bell casters were the only true artisans in the fair, the rest seem more like hobbyists. Our hostess in Cuneo, Franca, is a member of SERVAS, an international open house network, in which the members welcome fellow members into their homes on a reciprocal basis. With Franca we drive to a village in the Alpes Maritimes, Norat, where her daughter's family, like other city people, has a country retreat. Only two of the original families remain in the village. They had been mostly sheep and cattle farmers, and many had migrated to the plains about 50 years ago finding work there during one of the industrial upturns. The village houses are terraced into the hillside and most of them are abandoned, boarded up or falling down. A few of them have been renovated as second homes for people from the city, the old slate roofs replaced with tiles or, horror, synthetic sheet tiling. The tiny old church has a drinking fountain spouting clear spring water and the meadows are full of wild flowers. On the way to Torino near Chieri we stop at a tiny hamlet, Borgato Maria Della Rovere, for a night at the Cascina Macondo [http/www.cascinamacondo.com], a cultural centre run by Alessandra's friends Pietro Tatramella & Anna Maria. He is a storyteller and a writer of Italian haiku, she is a potter, a retired school teacher. Every weekday for 3 months in the summer Pietro entertains groups of schoolchildren with stories of American Indian traditions while Anna Maria gives classes in pottery. Next stop, Chieri. The textile industry here flourished without interruption from the 17th century to the 1980s. The earliest loom displayed in the textile museum dates from the late 1600s, when the shuttle was not yet known here. Instead, a notched stick carried the weft, a system in use for the next hundred years with the shuttle containing a bobbin introduced only in the 1700s, followed soon after by the fly shuttle. After that innovations were rapid, more healds were added, the structure of the loom changed from wood to iron and then steel, dobby and jacquard were introduced for elaborately woven brocade and tapestry in the 19th century. Electrical power began to drive the looms around 1904, shuttleless and then gripper looms came in the 1950s-60s, and at the end of the 20th century the first computerized models. The Museo del Tessile, housed in the former convent of the Poor Clares, has the earlier models on display in working condition, with warping wheels, spinning and dyeing equipment. There is a vast collection of documents available for research, and sets of early woven samples and trimmings. The Movimento Nonviolento is the Italian branch of War Resistance International, and has strong affinities with the teachings of Gandhi. The founder, Aldo Capitini translated Gandhi's writings into Italian and was responsible for the spread of the Gandhian principle of non-violent resistance in Italy. Professor Alberto L'Abate, Alessandra's father, is one of its pillars, he has worked with both Capitini and with Danilo Dolci. Professor L'Abate introduced the degree course in Peace Studies at the University of Florence where he has taught for many years, and is associated with the Studi Domenico Sereno Regis, a centre for research in Peace Studies in Torino, where we are expected that afternoon. Here we stay with Angela, a member of the Movimento Nonviolente; her husband Beppe who she met at a peace demonstration when she was 17, about 30 years ago, [he proposed 2 months later], is a member of the Movimento Internationale della Reconciliazione, which is related to the Church. Beppe grows organic vegetables and makes his own delicious Dolcetta Piemonte wine. Finally we reach Pescate, a suburb of Lecco, near the Swiss border. Eleanor and her sister look after us here, putting us up in their family home which backs onto the forested mountainside of a national park, Parco Monte Barro. In Lecco we give the last of our talks - earlier ones had been at Cascina Macondo and the Peace Centre at Torino - at a contribution supper to a gathering of about 35 Fair Trade supporters. We tell the story of Indian cotton textiles, relating past history to the present situation, with displays of khadi and malkha. Hardly anyone dozes off and there is a lively discussion to follow. Here in Italy the craft tradition provides a counter-flow to mass-production: as one declines the other is rejuvenated, an elliptical movement rather than a straight line. History is valued, the future is built on the past rather than by discarding or denying it. The village houses might be in ruins today, but no high-rises are allowed, so when the wheel of industry turns there is every chance of a renewal. Commercialism, the partner of mass-production, has not crept into every life: The members of SERVAS are hospitable through sheer goodwill and friendship, not for money. The movement for peace recognizes the relation between peace and artisan industry, and the Fair Trade organizations are groping their way towards fraternal relations with small producers on the other side of the world. The circles of hospitality, peace and fair trade are rich soils to nurture a renewed flowering of Italian craft. |

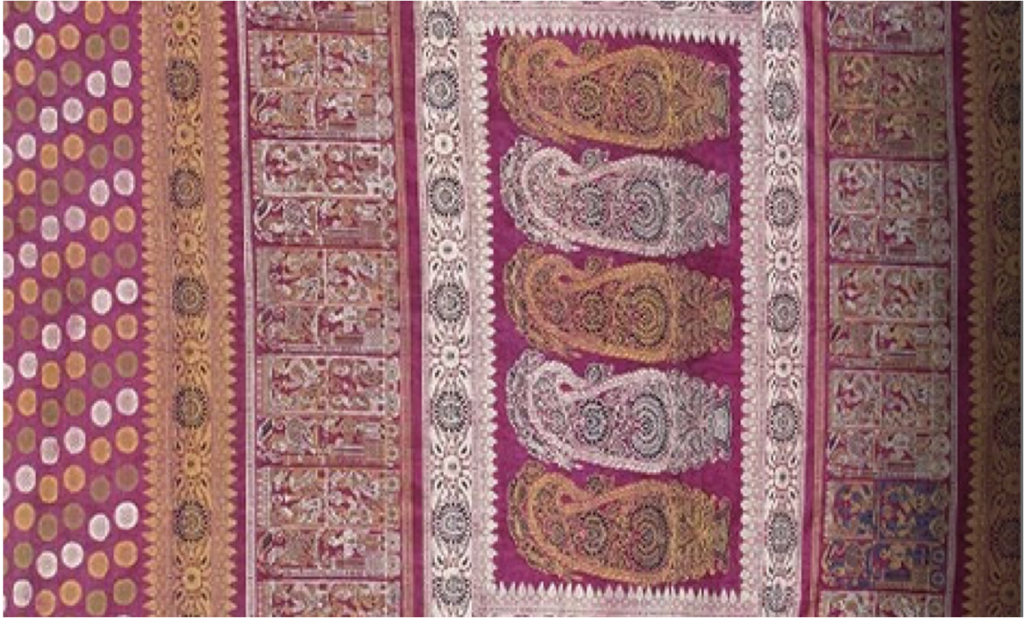

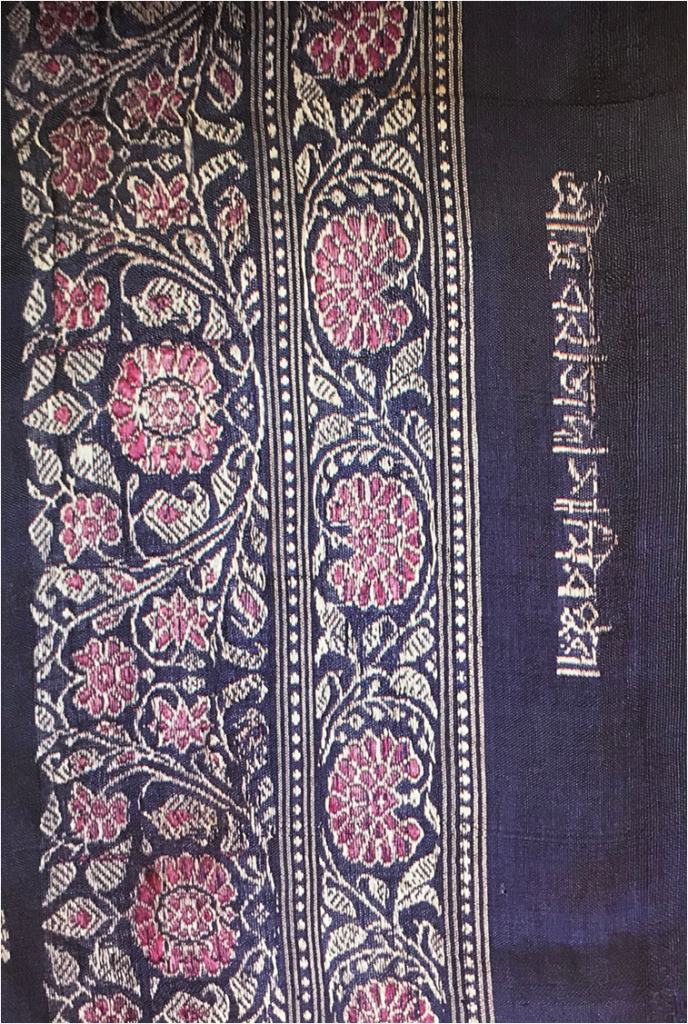

Although many people are involved with craft in America, both in terms of creation and purchasing, few are intimately entangled in the scholarly discourse of these Asian craft objects. The professors, curators and critics that do venture into the academic world of Indian craft often remain so far removed from the public sphere that little of this discourse ever becomes accessible to the public at large. This leaves most Americas with little information about the crafts they view in catalogues, high-end stores and import shops. As I have written before, there are certain organizations, such as Aid to Artisans that attempt cultural explanations with their sale of craft objects. However, these explanations barely breach the academic line, for lack of time, space and attention span of the buyer. There are also a few magazines that cater to the general public and are widely available at common venues such as book stores and magazines stalls. Ornamentations, one such magazine, recently featured the culture and jewelry of the Naga's from Northeastern India. Although much of the article focused on the dwindling art and the need for preservation, it proved to bring more of an explanation about the rich heritage of one of India's largest tribal areas. Among scholarly journals, available to the public only through personal subscription or large libraries, there are a few that focus on Asian arts and crafts. These journals, often published through universities with extensive doctoral programs for Asian art, create the majority of the American discourse around Indian art. The Freer Gallery of Art in the Smithsonian Institute and the Department of the History of Art at the University of Michigan publish one of the best journals, Ars Orientalis. Ars Orientalis has a wide spread readership among scholars and it is published as an annual volume of articles and book reviews focusing on all of Asia including the ancient Near East and the Islamic World. Fortunately, for scholars of Indian art and craft, the most recent publication is focused on western India in the 11th through 15th centuries. The volume contains articles with topics with a wide range, but mostly focused on textiles and trade. The contributing scholars, mostly from America and Britain, also included a professor from Jawaharlal Nehru University (New Delhi). However exciting an entire volume on Indian crafts truly is, the fact remains that most scholarly journals focus on ancient technology and production of these items. Even at that, the academics also tend to concentrate on what we in the craft world would consider classical pieces, e.g. Gandharan sculpture, Rajput paintings and Company School paintings. To find a discussion on more recent creations from artisan in India and elsewhere, often scholars must look to Anthropology journals where discussions of artifacts are mingled with stories of development and ethnographies. And these journals are perhaps even harder to obtain for the general public. There are, of course, occasional features in more accessible magazines or journals where India's contemporary crafts are highlighted. In the most recent summer edition of the journal The Subcontinent, which usually focuses on public affairs, the editors decided to feature articles dealing with the institutionalization of Indian arts and culture. A few of these articles concentrated specifically on some disappearing crafts such as puppet making and performance and hand-made paper creation. However, even features in more commonplace journals rarely reach the public in mass quantities. Perhaps the most successful way to introduce and educate the public about Indian crafts is through museums. In Washington, D.C., America's capital, the Smithsonian Institute has done a remarkable job of designing and filling museums that focus on non-western art and craft. The Freer and Sackler galleries are a part of this effort. Together they house some 1,200 objects from South Asia and the Himalayas that range in age from the 1st century B.C.E. to the present. They also show contemporary exhibits that highlight a scope of objects. In 2003, for example, the museum hosted an exhibit on Pakistani painted trucks (HTV's). Another fantastic museum located in the nation's capital is The Textile Museum. Through their gallery spaces, library and events, they promote knowledge of Indian craft to the public and academic classes alike. Currently the museum is hosting an exhibit on Kashmir shawls and the development of the buta design found on these spectacular fabrics. Also, this past October the museum held a conference on Indian Textile Traditions hosting speakers for such topics as carpet design, the impact of Kashmir shawls on Persian rug design and the disappearing flower motifs in Indian shawls. Museums such as the Freer and Sackler Galleries and the Textile Museum, as well as others throughout the United States, are perhaps the only ways through which the public can be educated about the vast array of Indian crafts. These museums and galleries are accessible, well advertised and contain easy to understand information on everything from wall paintings to rug weaving. However only so much information can be dispensed through didactic panels and catalogues. For people to have a deep understanding of Indian crafts they have a lengthy search ahead of them.

Broom-making is an extremely relevant example of using specialised craft skills to create items of everyday use - of the merging of utilitarianism and craft technique and skill in the artisans' hands. Broom-makers from village Kamedh in Ujjain in Madhya Pradesh, like the family of Sharada Verma, have been making brooms - from the leaves of the khajur or date-palm tree (Phonenix dactylifera) - for over seven generations. These families of broom-makers, the Bargundas, belong to the Khajurvanshi community. Their tradition - producing the very utilitarian 'broom', as a means of earning a livelihood - was not generally recognised as a 'craft'; neither were the broom-makers seen as 'craftspersons'. However, the skill required to make brooms from date-palm leaves, as well as the fact that the broom-making families are diversifying and also producing a host of decorative items from the date-palm leaf has led, eventually, to them being recognised as craftspersons.

PRACTITIONERS

Sharada Verma has been making brooms since she was nine years ole. She says that she learnt the skill as a child, by working with her parents and other members of her family, all of whom made brooms to sell for a living. In a regular workday, about 10-12 brooms are made, each of which can be sold for between Rs 10 and Rs 15. This tradition, as it is practised in Ujjain, is definitely hereditary. Sharada Verma was married into a family of broom-makers; her daughter, Rani, is married into a family of broom-makers; and her daughter-in-law is also from a family of broom-makers. Sharada Verma states quite candidly that since broom making is a profession through which the entire family earns its livelihood, and since it is a process in which women participate significantly, it is important when marrying off the sons to ensure that future daughters-in-law come from within the community and will participate in the family profession.

TECHNIQUE

PRODUCTS

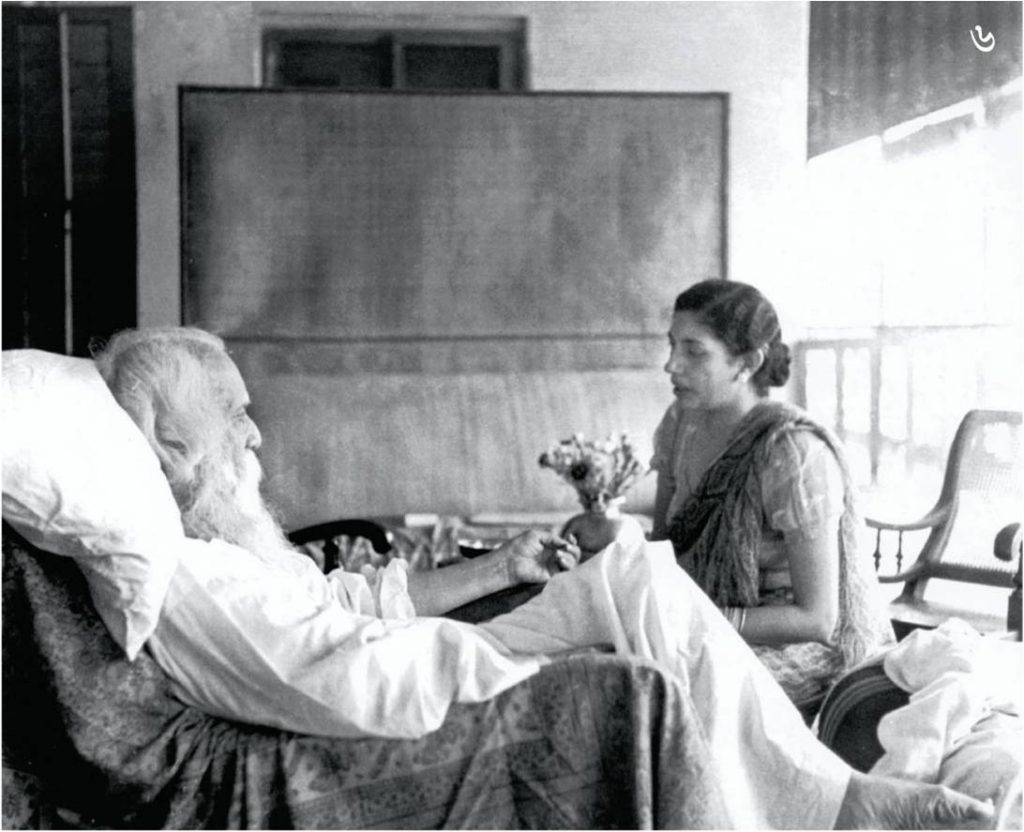

Issue #006, Autumn, 2020 ISSN: 2581- 9410 70 years of policy and practice Indian society is still governed by a rigid hierarchy, and evidence of this appears in every social structure. This explains the lowly status of the crafts in India and the impoverishment of craft communities who have to compete with mass produced industrial products today. The government school curriculum and timetable also reveals the status of art and craft education clearly in its hierarchical structure. Morning classes, when children are bright and rested are reserved for mathematics, science and language, while art and craft education and other ‘co-curricular’ activities are relegated to Friday afternoons, at the end of a tiring working school week. Need one say more? Though this is the prevalent reality, it is shocking that the school curriculum does not reflect the highly commendable and valuable recommendations made in National Educational Policies over the last 80 years. If we go back to the pre-independence era, great thinkers like Rabindranath Tagore, who set up Santiniketan in 1901, offered a creative alternative to the British School system. Tagore’s understanding of the role of arts in education was clear: ‘Literature, music, and the arts, are all necessary for the development and flowering of a student to form an integrated total personality.’ Rabindranath Tagore.

Shiv Lal, traditional potter from Delhi has enthralled school children, for forty years, with his skill and mastery. Source :Sanskriti Kendra Museums, New Delhi

As early as 1952-53 the first Education Commission for Independent India emphasized ‘the release of creative energy among students so that they can appreciate cultural heritage and cultivate rich interests, which they can pursue in their leisure and later in life.’ It recommended that every high school student should take on one craft, working with the hands, to develop a high standard of proficiency, understand the dignity of labour, and support themselves in later life.

The Kothari Commission Report of 1964-66, was more inspiring as it emphasized that in an ‘age which values discovery and invention, education for creative expression acquires added significance… The neglect of the arts in education impoverishes the educational process and leads to decline of aesthetic tastes and values.’ In its recommendations it highlighted the critical role of art education in achieving major educational goals, and the necessity of art education at all stages of schooling - from pre-primary to high school.

All three subsequent National Curriculum Frameworks of 1975, 1988, and 2000, repeatedly recommended the importance of art education for the ‘holistic’ development of the child. These Curriculum frameworks recommended that, ‘Art Education should concentrate on exposing the learner to folk arts, local specific art and other cultural components.’ An interesting new idea was that the arts programme should ‘promote values and appreciation of India’s common cultural heritage and the protection of the environment.’ This was possibly influenced by global trends of the 70-80s.

In 1979, the Centre for Cultural Resources and Training (CCRT) was established under the inspiring guidance of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay (First Chairperson) and Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan (First Vice Chair). CCRT’s primary role was to train in-service school teachers from government schools across the country in ways to improve their teaching of all disciplines, with the introduction of an understanding of India’s cultural heritage, art and traditional craft activities. For 40 years now, hundreds of teachers have been trained by traditional practitioners in puppet making, clay work, printing, painting to improve the students’ school experience.

In 2000, UNESCO’s Director General, issued a plea for ‘art education to be placed on an equal footing (with other subjects) at different stages of schooling.’ Finally, in 2005 the National Curriculum Framework for School Education, under the inspirational Directorship of Krishna Kumar, re-emphasized the critical role of art and crafts in education by making it a compulsory subject up to Class X. Art education was recognized for its role in the healthy mental development of students, and its contribution in enhancing creativity and appreciation of their cultural heritage and respect for each other’s work. The approach suggested that art education should be integrated with other subjects as a two way-process: in the form of content providing examples in social sciences, languages, science, and mathematics, and in the form of activities, projects and exercises to make school learning a joyful experience. Furthermore, the study of traditional crafts could be introduced as an optional elective subject for students of classes XI and XII for the CBSC board exam.

Shiv Lal, traditional potter from Delhi has enthralled school children, for forty years, with his skill and mastery. Source :Sanskriti Kendra Museums, New Delhi

As early as 1952-53 the first Education Commission for Independent India emphasized ‘the release of creative energy among students so that they can appreciate cultural heritage and cultivate rich interests, which they can pursue in their leisure and later in life.’ It recommended that every high school student should take on one craft, working with the hands, to develop a high standard of proficiency, understand the dignity of labour, and support themselves in later life.

The Kothari Commission Report of 1964-66, was more inspiring as it emphasized that in an ‘age which values discovery and invention, education for creative expression acquires added significance… The neglect of the arts in education impoverishes the educational process and leads to decline of aesthetic tastes and values.’ In its recommendations it highlighted the critical role of art education in achieving major educational goals, and the necessity of art education at all stages of schooling - from pre-primary to high school.

All three subsequent National Curriculum Frameworks of 1975, 1988, and 2000, repeatedly recommended the importance of art education for the ‘holistic’ development of the child. These Curriculum frameworks recommended that, ‘Art Education should concentrate on exposing the learner to folk arts, local specific art and other cultural components.’ An interesting new idea was that the arts programme should ‘promote values and appreciation of India’s common cultural heritage and the protection of the environment.’ This was possibly influenced by global trends of the 70-80s.

In 1979, the Centre for Cultural Resources and Training (CCRT) was established under the inspiring guidance of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay (First Chairperson) and Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan (First Vice Chair). CCRT’s primary role was to train in-service school teachers from government schools across the country in ways to improve their teaching of all disciplines, with the introduction of an understanding of India’s cultural heritage, art and traditional craft activities. For 40 years now, hundreds of teachers have been trained by traditional practitioners in puppet making, clay work, printing, painting to improve the students’ school experience.

In 2000, UNESCO’s Director General, issued a plea for ‘art education to be placed on an equal footing (with other subjects) at different stages of schooling.’ Finally, in 2005 the National Curriculum Framework for School Education, under the inspirational Directorship of Krishna Kumar, re-emphasized the critical role of art and crafts in education by making it a compulsory subject up to Class X. Art education was recognized for its role in the healthy mental development of students, and its contribution in enhancing creativity and appreciation of their cultural heritage and respect for each other’s work. The approach suggested that art education should be integrated with other subjects as a two way-process: in the form of content providing examples in social sciences, languages, science, and mathematics, and in the form of activities, projects and exercises to make school learning a joyful experience. Furthermore, the study of traditional crafts could be introduced as an optional elective subject for students of classes XI and XII for the CBSC board exam.

Guided programme for students to enable them to understand their cultural heritage and ancient craft skills, organized by Shobita Punja at National Museum, New Delhi.

In preparing this innovative approach in 2005, the esteemed members of the National Focus Group on Arts, Music, Dance and Theatre began their Position Paper with an overview of the problems faced by schools and the reasons why most of the recommendations made by previous Commissions had not been implemented in regular school practice over the last five decades.

According to the Focus Group, the major reason why art education was neglected in the school programme was because the Indian school system focused on ‘core subjects’ - science, mathematics and language. The school system was also completely crushed by the grueling test and exam system that encouraged rote learning. Science, mathematics and language are seen as important subjects, offering students future careers in medicine, commerce, and engineering. Teachers blame parents for their lack of interest in the social sciences as they see few job options in this field. The Government efforts to industrialize India soon after Independence and now to digitize it, have created a further chasm between the arts and science.

Teachers find evaluation of students’ progress easier in core subjects, using quantitative measures. Experts and teachers know that ‘students’ progress’ in art and craft education is hard to evaluate on a scale of 1-100 marks and needs a more interactive qualitative approach. Therefore, within the exam oriented school system, the recommendations of the Commissions were ignored and schools continued to concentrated on just the core subjects.

The second major obstacle was the shortage of trained teachers. Teacher Training Institutes/colleges do not have an innovative arts and crafts education programme that can be integrated into the teaching of all subjects, for pre-primary to high school classes.

Today, industry is seeking to hire creative and innovative people. With no proper arts programme in schools, students don’t have the opportunity to be creative, or learn how to problem solve while designing a craft, or find innovative solutions to common problems. Thus, India continues to copy and imitate designs created in other countries from light switches to space technology. These two reasons; poor teacher training and the exam orientation of the school programme have led to a mediocre system, dominated by rote learning with no space for creativity, arts and crafts for lakhs of Indian students year after year.

Designing new textbooks for the Heritage Crafts school programme

The 2005 Commission led to the formation of a Textbook Development Committee of experienced professionals: Laila Tyabji, Founder member, Dastakar, Jaya Jaitley, CEO, Dastakari Haat Samiti, Mushtak Khan, Deputy Director, National Handicrafts and Handloom Museum, and others. They assigned the development of the textbooks for CBSC to Feisal Alkazi, Director Creative Learning for Change and eminent Drama Educator and myself.

Trying to overcome the limitations of the existing system, we adopted an approach based on the well accepted format of the science syllabus prevalent in all schools in India that contained two integrated parts: theory and practical work. The school timetable is adjusted to enable students to learn both aspects, with two combined periods to complete their practical science activity, each week. Using this ‘core subject’ formula, we hoped to erase the notion that art education was an ‘extra curricular’ subject.

The textbooks explained to parents, teachers and students that several career options (design, industrial product design, architecture, interior design, museum education management of a craft initiative etc.) were available to students selecting this course for the school board exam. Most importantly, it was hoped that young people belonging to traditional arts and crafts communities would opt for this subject, assist their families in their ancestral crafts and be able to meet challenges of entrepreneurship and merchandising in a global era. The underlying idea of this school programme was to nurture a generation of ‘rasikas,’ students who had had enjoyable educational experiences in school, so they could appreciate and support the Indian arts and crafts all their lives.

To address the issue of lack of trained teachers to implement this programme, it was explained that India is fortunate to have crafts communities in every village, town and city, and this could serve the schools in many ways. It was suggested that students could visit local craft centres to see how artisans lived and worked, and experience the amazing skills that they had. For practical work too, local craft practitioners could serve as mentors and trainers. Another benefit for schools was that compared to science laboratories, craft materials were inexpensive and readily available.

Guided programme for students to enable them to understand their cultural heritage and ancient craft skills, organized by Shobita Punja at National Museum, New Delhi.

In preparing this innovative approach in 2005, the esteemed members of the National Focus Group on Arts, Music, Dance and Theatre began their Position Paper with an overview of the problems faced by schools and the reasons why most of the recommendations made by previous Commissions had not been implemented in regular school practice over the last five decades.

According to the Focus Group, the major reason why art education was neglected in the school programme was because the Indian school system focused on ‘core subjects’ - science, mathematics and language. The school system was also completely crushed by the grueling test and exam system that encouraged rote learning. Science, mathematics and language are seen as important subjects, offering students future careers in medicine, commerce, and engineering. Teachers blame parents for their lack of interest in the social sciences as they see few job options in this field. The Government efforts to industrialize India soon after Independence and now to digitize it, have created a further chasm between the arts and science.

Teachers find evaluation of students’ progress easier in core subjects, using quantitative measures. Experts and teachers know that ‘students’ progress’ in art and craft education is hard to evaluate on a scale of 1-100 marks and needs a more interactive qualitative approach. Therefore, within the exam oriented school system, the recommendations of the Commissions were ignored and schools continued to concentrated on just the core subjects.

The second major obstacle was the shortage of trained teachers. Teacher Training Institutes/colleges do not have an innovative arts and crafts education programme that can be integrated into the teaching of all subjects, for pre-primary to high school classes.

Today, industry is seeking to hire creative and innovative people. With no proper arts programme in schools, students don’t have the opportunity to be creative, or learn how to problem solve while designing a craft, or find innovative solutions to common problems. Thus, India continues to copy and imitate designs created in other countries from light switches to space technology. These two reasons; poor teacher training and the exam orientation of the school programme have led to a mediocre system, dominated by rote learning with no space for creativity, arts and crafts for lakhs of Indian students year after year.

Designing new textbooks for the Heritage Crafts school programme

The 2005 Commission led to the formation of a Textbook Development Committee of experienced professionals: Laila Tyabji, Founder member, Dastakar, Jaya Jaitley, CEO, Dastakari Haat Samiti, Mushtak Khan, Deputy Director, National Handicrafts and Handloom Museum, and others. They assigned the development of the textbooks for CBSC to Feisal Alkazi, Director Creative Learning for Change and eminent Drama Educator and myself.

Trying to overcome the limitations of the existing system, we adopted an approach based on the well accepted format of the science syllabus prevalent in all schools in India that contained two integrated parts: theory and practical work. The school timetable is adjusted to enable students to learn both aspects, with two combined periods to complete their practical science activity, each week. Using this ‘core subject’ formula, we hoped to erase the notion that art education was an ‘extra curricular’ subject.

The textbooks explained to parents, teachers and students that several career options (design, industrial product design, architecture, interior design, museum education management of a craft initiative etc.) were available to students selecting this course for the school board exam. Most importantly, it was hoped that young people belonging to traditional arts and crafts communities would opt for this subject, assist their families in their ancestral crafts and be able to meet challenges of entrepreneurship and merchandising in a global era. The underlying idea of this school programme was to nurture a generation of ‘rasikas,’ students who had had enjoyable educational experiences in school, so they could appreciate and support the Indian arts and crafts all their lives.

To address the issue of lack of trained teachers to implement this programme, it was explained that India is fortunate to have crafts communities in every village, town and city, and this could serve the schools in many ways. It was suggested that students could visit local craft centres to see how artisans lived and worked, and experience the amazing skills that they had. For practical work too, local craft practitioners could serve as mentors and trainers. Another benefit for schools was that compared to science laboratories, craft materials were inexpensive and readily available.

Text Books and Workbook for Classes XI and XII, NCERT. Source: Shobita Punja

We prepared two separate textbooks for the theory classes for Class XI and Class XII. The text book for Class XI called ‘Living Craft Traditions of India’ had 10 chapters that covered common crafts available in most states such as 1.Craft Heritage in the home, 2.Clay, 3.Stone, 4.Metal work, 5.Jewellery, 6.Natural Fibres, 7.Paper, 8.Textiles, 9.Painting and composite skills like 10.Theatre Crafts. Each chapter contained information about the antiquity of the craft, regional varieties, poems, and interviews with artisans. Each chapter also delved into the nature of the materials used in the craft, process and technology, design and use.

The Craft Traditions of India: Past Present and Future textbook for the theory aspect of Class XII began with an introduction to crafts in India, explaining how important crafts were as the second largest employment sector in India, second only to agriculture, that one in every 200 Indians is an artisan, and that Indian crafts are famous throughout the world, making this sector one of the highest contributors to export earnings in India. The wide ranging topics covered in this textbook may help to reveal our intent and purpose:

Unit I: Overview of the Past

Text Books and Workbook for Classes XI and XII, NCERT. Source: Shobita Punja

We prepared two separate textbooks for the theory classes for Class XI and Class XII. The text book for Class XI called ‘Living Craft Traditions of India’ had 10 chapters that covered common crafts available in most states such as 1.Craft Heritage in the home, 2.Clay, 3.Stone, 4.Metal work, 5.Jewellery, 6.Natural Fibres, 7.Paper, 8.Textiles, 9.Painting and composite skills like 10.Theatre Crafts. Each chapter contained information about the antiquity of the craft, regional varieties, poems, and interviews with artisans. Each chapter also delved into the nature of the materials used in the craft, process and technology, design and use.

The Craft Traditions of India: Past Present and Future textbook for the theory aspect of Class XII began with an introduction to crafts in India, explaining how important crafts were as the second largest employment sector in India, second only to agriculture, that one in every 200 Indians is an artisan, and that Indian crafts are famous throughout the world, making this sector one of the highest contributors to export earnings in India. The wide ranging topics covered in this textbook may help to reveal our intent and purpose:

Unit I: Overview of the Past

- Crafts in history

- Colonial Rule and Crafts

- Mahatma Gandhi and Self-sufficiency

- Handloom and Handicraft Revival (contribution of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Pupul Jayakar and others)

- Craft Community today

- Production and Marketing

- Crafts Bazaars

- Crafts in the Age of Tourism

- Design and Development

NCERT Crafts Text Book for Class XII - Chapter to teach students how to document crafts and crafts communities. Source: Shobita Punja

The most exciting part of this textbook writing project was the development of the third book, a practical workbook called ‘Exploring the Craft Traditions of India: Field Study and Application of Heritage Crafts’ that offered easy-to-implement activities and field trips for students and teachers.

This workbook was designed for Classes XI and XII to develop critical life skills with activities in class, as homework and class assignments. The first part focused on preparing for field studies and focused attention on craft objects used at home. Students were asked to examine, learn to look and ask questions about each object - how it was made, what materials were used, whether could they ascertain where it was made and by whom? etc. These exercises were designed to encourage students to look, think, learn, discover and find out, and urged them to become generators of their own understanding and knowledge.

The enquiry-based learning approach and interdisciplinary activities covered many topics taking students outside the home, to study local heritage, local markets and craft bazaars. There were exercises on critical issues of climate change, depletion of natural resources and the impact of packaging and marketing of products on the environment.

The second part of the book was dedicated to the development and preparation of Documentation Formats for crafts; using ones prepared by NID, Ahmedabad, students were given exercises on how to interview artisans, how to seek permissions, how to photograph the process of making a craft. Students were to create a documentation survey form and then experience using and improving it.

NCERT Crafts Text Book for Class XII - Chapter to teach students how to document crafts and crafts communities. Source: Shobita Punja

The most exciting part of this textbook writing project was the development of the third book, a practical workbook called ‘Exploring the Craft Traditions of India: Field Study and Application of Heritage Crafts’ that offered easy-to-implement activities and field trips for students and teachers.

This workbook was designed for Classes XI and XII to develop critical life skills with activities in class, as homework and class assignments. The first part focused on preparing for field studies and focused attention on craft objects used at home. Students were asked to examine, learn to look and ask questions about each object - how it was made, what materials were used, whether could they ascertain where it was made and by whom? etc. These exercises were designed to encourage students to look, think, learn, discover and find out, and urged them to become generators of their own understanding and knowledge.

The enquiry-based learning approach and interdisciplinary activities covered many topics taking students outside the home, to study local heritage, local markets and craft bazaars. There were exercises on critical issues of climate change, depletion of natural resources and the impact of packaging and marketing of products on the environment.

The second part of the book was dedicated to the development and preparation of Documentation Formats for crafts; using ones prepared by NID, Ahmedabad, students were given exercises on how to interview artisans, how to seek permissions, how to photograph the process of making a craft. Students were to create a documentation survey form and then experience using and improving it.

Visitors have the pleasure of designing and buying made-to-order Jooties and bags from local leather craftsman at the Mehrangarh Museum Trust’s International 3-day Music Festival held annually in Nagaur, Rajasthan. Source: Smita Mankad.

Each exercise was described simply and clearly (as an aid for teachers and students) with photographs, stories, interviews, and extracts from articles and books on crafts and this gave each activity its context and subtext.

The workbook concludes with activities for the application of skills learned in school and home – display techniques, creating a corner museum, decorating the Principal’s office, designing a poster for a local craft community, designing a toy for a blind child, designing sustainable packaging for a product etc. These were all creative problem solving activities that could be shared with the rest of the school to communicate the valuable learnings from this crafts programme.

The three textbooks once completed were discussed, improved and approved by the Textbook Committee and translated into Hindi and Urdu and published by NCERT in 2011 for the new CBSC curriculum. However, CBSC did not address inhibiting issues and hurdles (accommodation of this new course in the school syllabus, training and encouraging teachers) and the course dissolved into oblivion. Changes within the management of NCERT and governments drove the final nails into the coffin of the new arts and crafts programme that we had fought so hard for years to introduce into schools.

Looking to the future

In 2020, the year of Covid-19, while the country was in lockdown the central government hastily eliminated 30% of the school syllabus, removing vital knowledge areas like democracy, cultural diversity and climate change. A new National Education Policy was made public in August 2020 and like its predecessors, makes excellent and ambitious recommendations:

‘Pedagogy must evolve to make education more experiential, holistic, integrated, inquiry-driven, discovery-oriented, learner-centred, discussion-based, flexible, and, of course, enjoyable. The curriculum must include basic arts, crafts, humanities, games, sports and fitness, languages, literature, culture and values, in addition to science and mathematics, to develop all aspects and capabilities of learners; and make education more well-rounded, useful, and fulfilling to the learner.’

The chasm between policy and the reality of the Indian school system has widened over the decades. One may ask - is the complete overhauling of the educational system, with drastic improvements in teaching standards, with far-reaching investments in infrastructure, possible? Is it even conceivable in a country where the status of arts and crafts remains negligibly low, to appreciate the value of India’s enormous ‘cultural capital’ that could transform India’s social and economic life?

There are three global trends that may shift the balance; climate change and sustainability, industrial and digital demand for innovative ventures and creative young people, and the notion of responsible global consumption.

India has a growing number of dedicated, committed people in vital sectors of education and crafts, who believe that this is not the time to give up but to strive harder, as the need is greater today more than ever before. Young people, young practitioners of craft traditions need to now become advocates of their community, trained in digital techniques and media, to speak to the government and the public, in their language with facts and figures, using every social media platform; talks, articles, interviews, and meetings.

The education of young people in arts and crafts should not merely be in the school syllabus for enjoyment, or as a co-curricular activity but recognized as an essential component for the holistic development of a human being. The name of this school programme could be changed to something like ‘Creative Industries’ that may help to remove the stigma and give it a significant status in the school curriculum!

It may also be possible to use the content and activities of the three text books produced for NCERT and CBSC mentioned above to create teaching modules and online learning programmes for schools, colleges and a wider audience of house wives, professionals and for potential consumers. Material from books may be reworked to suit the new medium and activities be added regularly to keep the online learning platform alive. The central role of ‘creative industries’ in achieving Government and International Millennial Goals needs to be explained to the wider public.

By making creative activities an essential part of India school education at all levels, poverty can be eradicated; gender equality can be achieved by engaging and nurturing women artists; and young people can become self-reliant and live a dignified life with decent work and wages through learning skills. Introducing a course on creativity in schools would assure that the ‘quality education’ promised in NEP 2020 is more inclusive, and by teaching students about sustainable practices used by all crafts communities would help to cultivate values and behavior patterns to reduce waste and preserve natural resources. To link the study of creative industries to pressing global issue of climate change, students can be introduced to the idea of responsible consumption, then they can sensitize their family and society to appreciate that crafts, made by hand with natural materials, is one sure way forward to create a sustainable future for the planet.

Every country needs creative individuals, for a country is known not only for its contribution in science and technology, industry and business but also music, dance, architecture, art, films, literature and other creative industries. So through special awards and scholarships, possibly funded by the private sector, an entire new generation of creative young people from traditional craft communities and other backgrounds can be nurtured and sponsored to ensure the preservation of unique skills and to Make India Creative again.

References

Position Paper 1.7, National Focus Group on Arts, Music, Dance and Theatre, NCERT, 2006

Living Craft Traditions of India, Textbook in Heritage Crafts for Class XI, NCERT, 2008

Crafts Tradition of India: Past, Present and Future, Textbook in Heritage Crafts for Class XII. NCERT, 2011

Exploring the Craft Traditions of India: Field Study and Application in Heritage Crafts for Classes XI and XII. NCERT, 2010.

Textbook Development Committee

Chief Advisor - Shobita Punja, Consultant, Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, , New Delhi

Advisor- Feisal Alkazi, Director, Creative Learning for Change, New Delhi

Members

Aditi Ranjan, Principal Designer, NID, Ahmedabad

Jaya Jaitly, CEO, Dastakari Haat Samit, New Delhi

Laila Tyabji, Founder member, Dastakar, New Delhi

Member- Coordinator - Jyotsna Tiwari, Reader, Depart of Education in Arts and Aesthetics, NCERT, New Delhi

Visitors have the pleasure of designing and buying made-to-order Jooties and bags from local leather craftsman at the Mehrangarh Museum Trust’s International 3-day Music Festival held annually in Nagaur, Rajasthan. Source: Smita Mankad.

Each exercise was described simply and clearly (as an aid for teachers and students) with photographs, stories, interviews, and extracts from articles and books on crafts and this gave each activity its context and subtext.

The workbook concludes with activities for the application of skills learned in school and home – display techniques, creating a corner museum, decorating the Principal’s office, designing a poster for a local craft community, designing a toy for a blind child, designing sustainable packaging for a product etc. These were all creative problem solving activities that could be shared with the rest of the school to communicate the valuable learnings from this crafts programme.

The three textbooks once completed were discussed, improved and approved by the Textbook Committee and translated into Hindi and Urdu and published by NCERT in 2011 for the new CBSC curriculum. However, CBSC did not address inhibiting issues and hurdles (accommodation of this new course in the school syllabus, training and encouraging teachers) and the course dissolved into oblivion. Changes within the management of NCERT and governments drove the final nails into the coffin of the new arts and crafts programme that we had fought so hard for years to introduce into schools.

Looking to the future

In 2020, the year of Covid-19, while the country was in lockdown the central government hastily eliminated 30% of the school syllabus, removing vital knowledge areas like democracy, cultural diversity and climate change. A new National Education Policy was made public in August 2020 and like its predecessors, makes excellent and ambitious recommendations:

‘Pedagogy must evolve to make education more experiential, holistic, integrated, inquiry-driven, discovery-oriented, learner-centred, discussion-based, flexible, and, of course, enjoyable. The curriculum must include basic arts, crafts, humanities, games, sports and fitness, languages, literature, culture and values, in addition to science and mathematics, to develop all aspects and capabilities of learners; and make education more well-rounded, useful, and fulfilling to the learner.’

The chasm between policy and the reality of the Indian school system has widened over the decades. One may ask - is the complete overhauling of the educational system, with drastic improvements in teaching standards, with far-reaching investments in infrastructure, possible? Is it even conceivable in a country where the status of arts and crafts remains negligibly low, to appreciate the value of India’s enormous ‘cultural capital’ that could transform India’s social and economic life?

There are three global trends that may shift the balance; climate change and sustainability, industrial and digital demand for innovative ventures and creative young people, and the notion of responsible global consumption.

India has a growing number of dedicated, committed people in vital sectors of education and crafts, who believe that this is not the time to give up but to strive harder, as the need is greater today more than ever before. Young people, young practitioners of craft traditions need to now become advocates of their community, trained in digital techniques and media, to speak to the government and the public, in their language with facts and figures, using every social media platform; talks, articles, interviews, and meetings.

The education of young people in arts and crafts should not merely be in the school syllabus for enjoyment, or as a co-curricular activity but recognized as an essential component for the holistic development of a human being. The name of this school programme could be changed to something like ‘Creative Industries’ that may help to remove the stigma and give it a significant status in the school curriculum!

It may also be possible to use the content and activities of the three text books produced for NCERT and CBSC mentioned above to create teaching modules and online learning programmes for schools, colleges and a wider audience of house wives, professionals and for potential consumers. Material from books may be reworked to suit the new medium and activities be added regularly to keep the online learning platform alive. The central role of ‘creative industries’ in achieving Government and International Millennial Goals needs to be explained to the wider public.

By making creative activities an essential part of India school education at all levels, poverty can be eradicated; gender equality can be achieved by engaging and nurturing women artists; and young people can become self-reliant and live a dignified life with decent work and wages through learning skills. Introducing a course on creativity in schools would assure that the ‘quality education’ promised in NEP 2020 is more inclusive, and by teaching students about sustainable practices used by all crafts communities would help to cultivate values and behavior patterns to reduce waste and preserve natural resources. To link the study of creative industries to pressing global issue of climate change, students can be introduced to the idea of responsible consumption, then they can sensitize their family and society to appreciate that crafts, made by hand with natural materials, is one sure way forward to create a sustainable future for the planet.

Every country needs creative individuals, for a country is known not only for its contribution in science and technology, industry and business but also music, dance, architecture, art, films, literature and other creative industries. So through special awards and scholarships, possibly funded by the private sector, an entire new generation of creative young people from traditional craft communities and other backgrounds can be nurtured and sponsored to ensure the preservation of unique skills and to Make India Creative again.

References

Position Paper 1.7, National Focus Group on Arts, Music, Dance and Theatre, NCERT, 2006

Living Craft Traditions of India, Textbook in Heritage Crafts for Class XI, NCERT, 2008

Crafts Tradition of India: Past, Present and Future, Textbook in Heritage Crafts for Class XII. NCERT, 2011

Exploring the Craft Traditions of India: Field Study and Application in Heritage Crafts for Classes XI and XII. NCERT, 2010.

Textbook Development Committee

Chief Advisor - Shobita Punja, Consultant, Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage, , New Delhi

Advisor- Feisal Alkazi, Director, Creative Learning for Change, New Delhi

Members

Aditi Ranjan, Principal Designer, NID, Ahmedabad

Jaya Jaitly, CEO, Dastakari Haat Samit, New Delhi

Laila Tyabji, Founder member, Dastakar, New Delhi

Member- Coordinator - Jyotsna Tiwari, Reader, Depart of Education in Arts and Aesthetics, NCERT, New Delhi

Aruvacode, a small village near Nilambur in North Kerala had in the past been well known for its highly skilled potters. About one hundred families of traditional potters continued to follow their trade of making pots, household utensils and other objects. However a scarcity of clay, firewood and other raw material, the influx of cheap industrial substitutes coupled with a lack of demand for the finished product had resulted in a sharp decline in the economic and social status of the artisans resulting in dire poverty. By 1993 many of the potters had taken to distilling spurious liquor while the women resorted to prostitution.

For the revival of a languishing craft and the dignified survival of potter families of Aruvacode an intervention was undertaken by the NGO, Dastakari Haat Samiti.

Period: March to September 1993

Team: Jaya Jaitly (Project Director)

K.B.Jinan (Chief Designer)

Vishaka (Technical Designer)

Ulasker Dey (Technical Expertise, Regional Design Technical centre, Bangalore).

Objectives

Phase I

Step 1

ESTABLISHMENT OF FACILITIES

TRAINING

The children of the community were always at the project site drawing, creating in clay, playing with the created pieces, giving suggestions. The children added a new dimension and infused a fresh wave of enthusiasm.

During the summer vacation of two months all the children in the village joined the project. They were considered as trainees during this period. Films, field trips, puppet shows, story telling were all part of their training.

The women trainers were good at creating circular objects - this shape was easy for them as the food they cooked was often of a circular shape. Once they made the connection with clay they related to the work and with great improvement continually developing their own style. Figurative work, coiling and pinching methods, bead making and jewellery were then introduced.

INTERACTION FOR MARKETING

PARTICIPATION IN HANDICRAFT EXHIBITIONS IN COIMBATORE, BANGALORE, NILAMBUR, ERNAKULAM

THE MOCK SHOP:Towards the end of the program when a fairly large and good range of products had been created an impromptu mock shop was set up. The idea was to create consciousness of a customer-artisan exchange and to create awareness of consumer needs. The mock sales also allowed for comments on each others and their own works - objectively, sportingly and from the customers point of view.

LONG TERM ISSUES IDENTIFIED:

FUTURE OF THE PROJECT:The main efforts of the project were in revival of the skills and the dignity of the village. The most important activity needed in the future was to develop regular markets for their products and for the potters to learn the intricacies of the market mechanism External support was still required especially in marketing.Phase IIK. B. Jinan returned to Aruvacode, formed an NGO called Kumbham, and started a design and marketing project of terracotta suited for the modern context. The product ranges created with the Aruvacode potters included objects for use in architecture, in homes, offices and gardens. Jinan moved into the village overseeing and designing the products. He stayed on in the village even after the project was over to help put the potters on their feet. 'When an entire village proves that it wants to turn over a new leaf, it is a civilised society's responsibility to respond with sensitivity.' Over the last few years many products have been created and marketed which are notable for their form as well as function. Kumbham products now find wide acceptance in households, corporate offices, hotels and resorts. |

The Ayodhya (Uttar Pradesh) skyline is dotted with vimanas and every street hosts a temple or two. Peals of bells greet you five times a day. This small town was wrecked with religious riots in 1990 when Hindu fundamentalists attacked and destroyed the Babri Masjid. Today, this extremely violent recent history is not much in view and devotees and priests go about their business indulging the sacred tourist trail. Off the main street, nestled between tea stalls, is Shyam lal's home, studio and shop. Though his main business these days are marble sculptures his specialty and family tradition are Ashtadhatu (eight metal) religious sculptures. Ashtadhatu is an amalgam of copper, tin, lead, antimony, zinc, iron, gold, and silver. Due to its expense it is fast becoming a languishing craft. Shyam Lal refuses to put a price on his sculptures. His belief is that gods cannot be bought or sold and so he only takes an honorarium for his "work of faith".

THE ART OF IMAGE MAKING

In Indian sculpture, the human form is composed of various compact, curved, and almost geometric shapes assembled according to an ideal canon of proportions. Whether globular or pearlike, cylindrical or conical, these components are rounded volumes that seem filled to capacity: muscles appear to have melted away, bones are invisible, and skin is stretched smooth and tight. The sense of inner vitality that pervades most Indian figural sculptures is conveyed not only by limbs and torsos that seem to be inflated with breath (prana), but also by sinuous poses. Figures are modeled with a fluidity that allows the parts of these pliant bodies to glide almost imperceptibly into each other. Nothing truly interrupts this inner movement or the surface that contains it, not even the garments and jewelry that accompany and accentuate the body's sensuous shapes.

A FIND IN AYODHYA

The Ayodhya (Uttar Pradesh) skyline is dotted with vimanas and every street hosts a temple or two. Peals of bells greet you five times a day. This small town was wrecked with religious riots in 1990 when Hindu fundamentalists attacked and destroyed the Babri Masjid. Today, this extremely violent recent history is not much in view and devotees and priests go about their business indulging the sacred tourist trail. Off the main street, nestled between tea stalls, is Shyam lal's home, studio and shop. The innocuously small doorway is decorated with a large marble image of Hanuman. Peer into the dark interior and a plethora of sculptures assail your vision. Negotiate the tiny maze deeper into his home and you encounter floors and floors of every conceivable religious idol both in stone and metal. Pushed to show his specialty and he'll take you up three floors into a small room where he shyly opens cupboard upon cupboard of Ashtadhatu (eight metals) sculptures.

TECHNIQUE OF ASHTADHATU

Ashtadhatu is an amalgam of copper, tin, lead, antimony, zinc, iron, gold, and silver. The metal sculptures were cast using the cire perdue process. First, a wax model of deity (or any figure) is made. Over this wax model, a clay mould is made. The clay mould is applied in three layers to contain the wax. After the clay around the wax is dried, the wax is heated and poured out. Molten metal is poured into the clay mould taking the shape of the hollowed space created by the draining of the wax. The eight metals are in roughly equal proportions though now with the increasing prices of precious metals these are now being added in diminishing proportions. Once the metal is cooled and set, the outer mould is broken. The image thus created is of rough finish and lots of work goes into polishing, filing and finishing the resulting solid sculpture. Clothes are painted onto the finished sculptures. Lastly, the eyes of the sculpture are fixed. These are made from conch shells. Paint dulls over the years but conch shell retains its pearliness over decades. Ashtadhatu sculptures are made so as to be durable and last years without noticeable decay. The underlying aim of the artist is to make idols which last, are beautiful and as natural as possible.

THE MONEY FACTOR

When asked the price of his sculptures, Shyam Lal demurs. In his opinion he creates images of god and how can a price be placed on such an object. He prefers to call it an honorarium otherwise the art will become restricted to the rich. He admits that his market is minimal. Firstly, he only makes religious idols so his market is restricted. Secondly, because the sculptures require a host of metals, some of which are quite costly this makes the images expensive propositions. Also a medium sized idol takes up to a month to make which makes it time costly. Suggestions towards reducing the cost of production are met with disdain as he believes that any attempts to alter this age old art will cheapen the value of the god. It is as he calls it "Dharam ka Kaam" (work of faith).Shyam Lal can be contacted at: Adarsh Murti Kala Kendra Corner of Hanuman Garhi, Opposite Tulsi Smarak Bhavan, Rani Bazaar Crossing, Ayodhya, Distt. Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh Tel: 05278 32705

|

Background: Avani means ‘The Earth’ in Sanskrit. All our activities support the environment and the people of the area where we are working. Avani has been working with integrating sustainable livelihoods and appropriate technology. The focus of our work has been creation of livelihood opportunities in remote rural areas where supplementary cash income for daily needs is very necessary for the families that continue to live in the villages. With decreased productivity of land and fragmented land holdings it is becoming more and more difficult for small farmers, traditional artisans and unskilled, landless wage earners to make a living while staying in the villages. Our work provides the choice to some families to have a source of income in their village through farm-based activities, traditional craft and appropriate technology. In its entirety, our work spreads across 71 villages in two districts of Bageshwar and Pithoragarh. Our main focus has been the capacity building of rural youth to manage all aspects of the different activities. Our team is entirely from villages where we work. |

|

| Through Avani’s work, solar technology has reached remote villages. More than 1500 rural families in about 228 remote hamlets and villages are now using solar lights. Our work has ensured that the community has the technical and the financial capacity to ensure the long term functioning of these systems. At present this program is self-sustaining and managed by the village committees. |  |

Over 40 rural youth have been trained to assemble, repair and maintain solar equipment. The training of women technicians has emerged as an area where women get an equal opportunity to use their skills. Traditionally they are not allowed or encouraged to handle tools. The village energy committees have collected more than 31 lakh rupees of their own, for future replacement of batteries and panels which is managed by the members themselves.

Avani is also working with the thermal applications of solar energy like solar water heaters and solar driers. We have set up a rural mechanical workshop and trained local youth to manufacture Solar Water Heaters and Solar Driers. This unit has generated business by selling water heaters to private homes, resorts, hotels and a hospital.

The Avani centre is also powered by Clean Energy. A solar generator of 8 kW capacity, produces electricity for lighting, computers and light machines.

PRODUCTIVE USE FOR WASTE MATERIAL (PINE NEEDLES) AND RAINWATER HARVESTINGIn its quest for finding a productive use for waste material, Avani has been working with setting up a pine needle gasification unit that produces 9 kW of electricity by burning pine needles alone. This gasification system is the first of its kind that uses 100 per cent pine needles as feedstock. This gasifier has been developed in collaboration with a gasifier manufacturing company. |

|

Pine needles are a major cause of forest fires in our area, leading to loss of biodiversity. The pine trunk being fire resistant propagates itself, thus encroaching on mixed forests in the vicinity. The pine needles also do not allow water recharge, thereby reducing the moisture content in the soil. As a result, a pine forest rarely has any undergrowth due to high acidity and low moisture of the soil. Removing it from the forest floor would have many benefits including natural regeneration of forests, increased soil moisture and better recharge of groundwater. |

| We are now planning to extend this technology to the villages where gas produced by the gasification of pine needles can be used for cooking. As part of its work on rainwater harvesting, Avani has also constructed nine Rainwater Harvesting Tanks at nine government schools, that collect almost 3,00,000 litres of rainwater for drinking for the school children. At all the Avani centres, the daily needs are met through rainwater. At the Avani centre IN Tripuradevi, water from all rooftops goes into an underground storage system which has a capacity of 3, 25,000 litres. It takes care of the daily needs of a community of 30 residents, trainees, including all the textile processing and irrigation for vegetables. We have demonstrated the appropriateness of using rainwater in water deficient areas in the hills. | |

LIVELIHOOD OPPORTUNITIESSaukyura, a village of traditional artisans was one of the first villages to use solar lighting. When the artisans expressed their inability to pay for the technology, it was felt that to take the technology to the poorest of the poor, work needed to be done to enhance their incomes. It was then decided that Avani would work with the revival and preservation of the traditional skill of weaving and spinning to create livelihood opportunities in the area. It would then ensure that the poor families are also able to access technology. |

|

| Traditionally, the Shauka community was working with Tibetan Sheep wool and the Bora Kuthalia community was working with hemp fibre. It became increasingly difficult to make a sustainable living with this craft. The reason was that coarse Tibetan wool products do not have a ready market and plastic ropes and sacks have taken over the local demand for hemp products. The legality of growing and using hemp fibre is also very ambiguous. Consequently, in both these communities, the younger generation was abandoning the craft due to insufficient returns. To make this intervention successful, we needed to redefine this craft as contemporary and we had to make sure that it brought income to the families. |  |

Another very important aspect of this intervention was its’ effect on the soil and water of the area. We then decided to work only with natural dyes for the coloring of our textiles.

|

|

|

The management of the textile enterprise is completely decentralized and it is ensured that the work reaches the artisan in their village. To strengthen our work with natural dyes in textiles we are also exploring other applications of natural dyes and introducing the cultivation of dye plants in the villages as a livelihood option. |

We have encouraged the women’s groups to collect and grow dye plants like turmeric, myrobolan, and pomegranate rind and walnut hulls. They have already started the cultivation of turmeric and are protecting the saplings and trees of other dye yielding species.

Some of the materials we use for natural dyes are:

|

|

| We are now working with the use of plant as mordant as well as the dye. We are trying to replace the salts we use for fixing the color with plant mordants e.g., berberis fruits and leaves are used as natural mordants for madder. We are continuously researching new dye yielding plants. We are using a weed called Eupatorium that grows wild in our hills and gives us different shades of green and mustard. Turmeric Root and Marigold flowers are used for different grades of yellow. Our color palette in wool and silk in natural dyes is now quite extensive. |  |

To begin with, we just reintroduced the use of Natural Dyes in Carpets and Tweeds made by local artisans. Then we developed a range of very contemporary products in natural dyes. The blends that we created were as follows:

|

|

|

The active participation of the community has formed the basis for a sustainable livelihood base with environment friendly products. Over 500 artisans are involved in creating wool and silk textiles in Natural Dyes.

The enterprise is able to provide supplementary cash income to the spinners and an alternative livelihood to the weavers.

The artisans’ collective has now been registered as the Kumaon Earth craft Self Reliant cooperative that will be managed by the community.

As mentioned before, the process of production is as important as the product itself. Therefore, we are very conscious that the soil and water of the area should not be adversely affected by this enterprise. So we have ensured that it is a closed cycle of use where all the waste is recycled.

|

| All finished textiles are calendared with a calendaring machine that is powered by solar energy or with electricity produced by the pine needle gasifier. Another application of natural dyes is in natural colors for painting on paper. We have created a whole range of colors that are non-toxic and eco friendly. They are very appropriate for young children as well. Another traditional application of turmeric is making Roli or peetha as it is called locally. We are now looking at selling it in the local market as well as the urban markets. |  |

The cultivation and collection of natural dyes can become a sustainable livelihood option as these plants can be:

MOTIVATION BEHIND THE WORK AND LIFESTYLEWe reached the Himalayas with a personal aspiration to live in the hills while contributing to the area.

|

|

Company Profile Headquartered in Balaramapuram, Kerala (Southern India), the Handloom Weavers Development Society (HLWDS) is a non-governmental organization that works to improve the welfare of deprived, marginalized and downtrodden handloom weaving communities in Kerala. Vision A flourishing handloom weaving industry preserving Indian culture and providing a decent standard of living to weaver families. Mission To provide employment to weaver families in Kerala through providing looms and associated services, so that they can enjoy a better standard of living and preserve their heritage and culture. History The Handloom Weavers Development Society was established in 1989 by a group of twenty four young weavers from the Balaramapuram area of the district of Trivandrum, Kerala. The invention of the power loom, the recurrence of sweatshop manufacturing and a competitive global textile market was stripping handloom weavers of their market. These young weavers organized to discuss ways to overcome the plight of the handloom weaving sector and to put an end to the oppressive labour arrangements and corruption that was occurring in the sector.With the assistance of a five-year grant from the Ford Foundation, HLWDS has made significant strides in its long-term goal of diversifying handloom production. HLWDS has successfully piloted several training programs in alternative hand produced textile techniques including new designs, block printing, batik, tie and dye, kalamkari, and Ayurvedic dyeing.Their experimentation with Ayurvedic dyeing has been one of their most successful product diversification initiatives. With the financial support of the Government of Japan, HLWDS established an Ayurvedic dye house in Balaramapuram, which was inaugurated by MR. RIYOZU KIKUCHI, Consul General of Japan on 7th September 2004. The Ayurvedic dye house is equipped with modern machineries and facilities to produce pure Ayurvedic herbal handloom clothes. The minimum production capacity of their dye house is nearly 1000kg per day. Also in 2005, the Government of India generously granted Rs: 850,000 to assist the HLWDS for establishing a common facility center for Ayurvedic dyeing on handloom clothes and to standardize Ayurvedic dyeing.

PROGRAMMES, SAVINGS AND CREDIT

Self Help Groups (SHGs) are the main conduit for the majority of their programming. HLWDS' SHGs assists women in becoming independent producers of hand loomed products. They assist women weavers in purchasing material supplies, weaving accessories and equipment. They also act as a safety net for participants who may borrow for urgent consumption needs. Through these SHGs women weavers are able to break their exploitative arrangements with master weavers and to end cycles of debt. Currently, they work 731 SHGs in 51 villages.WEAVING PRODUCTION ASSISTANCE

HLWDS works to improve the livelihoods of weavers by providing production assistance aimed at overcoming the obstacles of scarce supplies, shrinking resources, lagging technological improvements and competitive markets (i.e. power loom). They also try to provide alternatives to exploitative supply and marketing arrangements with master weavers and bogus handloom societies.Their production assistance activities include:

- Seasonal Inputs Provision To prevent material supply shortages, HLWDS purchases bulk supplies of threads and inputs from the Government Thread Bank for sale at reasonable prices to local weavers during festival production season.

- Equipment /Inputs Loans Through its savings and credit program HLWDS provides loans for purchase of looms, spinning wheels, weaving accessories and inputs. HLWDS assists participants to acquire looms through government programs.

- Loom Maintenance On a consultancy basis, HLWDS connects master weavers and loom repairers with weavers experiencing trouble with the functioning of looms.

Product Diversification Training

- HLWDS provides training assistance to handloom weavers from various parts of the state. They provide training in Ayurvedic dyeing; block printing, weaving, tie and dye, embroidery and design.

Marketing

- HLWDS purchases output from weavers at a fair price and sells in their retail showroom and at exhibitions. They have also planned to sell weavers' product to private retailers charging a small fee from producers for the marketing service.

- They also provide training assistance on marketing techniques.

- HLWDS undertakes the marketing of experimental products including

MEDICAL CLOTH

Handloom Advocacy HLWDS fights to retain government support for the handloom industry through campaigning, networking and lobbying. Through their handloom advocacy program, they provide a voice to handloom weavers across Kerala. Some of the activities include:Networking

HLWDS is a member of South Indian Handloom Weavers Organizing Committee (SIHWOC), a regional network, and the Handloom Protection Forum, a state network.Lobbying

HLWDS has developed contacts with officials involved with setting and carrying out policies and programs affecting the industry. Meet officials to lobby for policy change and give testimony on conditions in the sector.Awareness

They also hold seminars to educate handloom weavers about government policies and how to protect themselves from corrupt cooperative societies that falsely claim financial resources in the name of handloom weavers.HANDLOOM SECTOR ISSUES

Occupational Health Hazards HLWDS works to reduce occupational health hazards and injuries among weavers and their families. It is far too common for weavers to suffer from a variety of occupational health hazards including respiratory ailments from breathing in particulate dust in poorly ventilated workspaces and repetitive motion injuries that leave many weavers disabled. Through ILS, they have documented these health problems and presented them to government officials in an effort to raise awareness of the plight of the weavers. Currently, HLWDS conducts health training around issues of occupational diseases (respiratory illness and repetitive motion injury).Education and Child Labor

Through ILS, the HLWDS learned that there were high levels of child labor and overall low levels of education among HLWDS members. To address these problems, HLWDS established day cares centers, non-formal education programs for adults and children, vocational training, and cultural programmes that aim to decrease child labor and increase the level of education among weaving families.Gender Equity

HLWDS also works with gender equity issues by raising awareness, supporting advocacy efforts, and training leaders to address gender bias and discrimination issues. Their gender work is primarily facilitated through SHGs.RESEARCH AND DOCUMENTATION