JOURNAL ARCHIVE

| I first saw kasuti embroidery on one of Kamladevi Chattopadhyaya’s saree blouses. My father and she enjoyed a gently flirtatious relationship. By then most people treated her with the affectionate deference due to the grandmother of Indian craft, and she rather relished being reminded that he had first seen her wrapped in gold tissue and jewels on a tiger skin, acting in a verse drama of the 30’s. Kamladevi’s knowledge of Indian craft techniques was encyclopedic though not at all academic. For most people – even lovers of craft – the word kasuti, although it is one of India’s oldest embroideries, raises an enquiring eyebrow. Partly because it has never been commercially exploited, partly due to the rather stepmotherly treatment the crafts of North Karnataka (once part of Bombay State) are given by the Karnataka State Government. You are unlikely to find kasuti in CAUVERY, the Karnataka State Handicrafts Emporium, overflowing with the more opulent silks, ivories and marquetry of the southern Mysore State. But kasuti’s low profile image is also due to the gentle, reclusive nature of the women who craft it. Quite unlike the exuberantly entrepreneurial Gujeratis and Rajasthanis whose mirrorwork and satin floss embroideries floods the Janpath pavements and Surajkund Mela. Once seen, I was haunted by kasuti. It was such an elegant, subtle embroidery - the stitches geometric and delicate, but creating elaborate, dramatic images. Kasuti is a combination of four different stitches, all based on the counted thread principle: gavanti and murgi: diagonal zig-zag running stitches similar to the Holbein stitch in Elizabethan blackwork; menthi: a minute cross-stitch, and negi: pattern darning creating a woven effect with extra weft threads. Traditionally, kasuti was only done on the borders, pallav and khand blouse of the blue-black, indigo dyed Chandrakala saree that was an essential part of the trousseau of brides in the Dharwad-Hubli belt of north Karnataka. All four stitches are used together in each saree, but each motif is done only in one stitch, using a single embroidery thread. The larger motifs are near the pallav border, tapering off gradually till the body of the sari has only a tiny, all-over, floral buta or star. The motifs, done in flaming pinks, yellows, greens, purples, reds and whites, are pictorial -ritual and votive in character: the Tulsi plant and temple chariots - 8-pointed stars, parrots, paisleys and peacocks - howdah-ed elephants, the Nandi sacred bull - bridal palanquins, cradles, and flowering trees. The symbolic, not particularly politically correct message is that the wearer should be fertile and welcoming and worship her husband as God! Not a women’s lib saree, perhaps, but still a stunningly beautiful one… Mukund Maigur, a quiet, gangling young man working in a printing press in Hubli, seemed an unlikely crusader for craft. However, stemming from a chance encounter with an unemployed indigo dyer-weaver some years before, his concern had become an obsession. It had led him into forays into villages in search of dyers, durrie-makers, weavers and embroiderers, and into battles with bureaucrats and bank managers to secure them support, finance and orders. Eventually it led him to our DASTKAR office. His attempt to get a bank loan of 25,000 rupees to start a cooperative was in its third unsuccessful year. A senior bank official had told him, “This craft is bound to die; why are you bothering?” Going with Mukund to Dharwad-Hubli to work with indigo dying and the Irikil saree weavers, I was also intent on kasuti. I felt if we revived and combined the three traditions it would be crafting a solution that was both aesthetic and economic - generating employment and earning in an area suffering from drought and neglect. The death of local craft traditions was a loss not only of cultural heritage and creativity, but of daily bread. Ekbote, a dyer in Gadagbetigiri with eight dependents, had recently been forced to close his indigo vat for lack of orders. Despite the skills of an 800 year old family tradition in dying, he was now earning two rupees a day as casual labour. We decided to do kasuti on a range of sarees dyed and woven by local weavers in traditional colours and designs - Irikil and Chandrakala sarees with the typical garhidhari, paraspeti and nagmuri borders and toptheni pallavs. We also introduced more vivid colours and combinations: emerald and purple, rani pink and navy, saffron and terracotta, (traditionally the Irikil saree borders are always a dark maroon.) as well as dupattas - for younger customers with limited budgets. A few sarees were ordered in silk. Our first problem was identifying and forming a group of women. The women who embroidered the kasuti sarees and khands lived in villages and small towns, isolated from each other, uneducated, unorganised, desperately poor. They learned stitches and motifs from their mothers, occasionally embroidering a saree for a richer neighbor, with no idea that their skill could have long-term material returns. We plodded from village to village, talking to women and listing their names. By then the monsoon rains had started. It meant we had to abandon our three-wheeler and squelch through the flooded fields; but it also meant we got a very warm welcome! The local manager of CAUVERY happened to be at one of the villages where I was ordering sarees, “These are Granny’s sarees! Who will buy them?” was his amazed response. The word soon spread that the skill the women had taken for granted was worth something to this funny stranger from Delhi. By my next visit, Kasuti embroiderers began to descend on my room at the Nataraj Boarding Lodge in Dharwad. So poor they could not afford the 2 rupees bus fare, they walked two or three hours in the burning summer heat from their villages. But proud of their heritage and its symbolism, they firmly stated their terms: they would work their fingers to the bone for fair wages, but they would not alter their designs or put ritual motifs where people might sit on them. When they heard that what I wanted was their traditional saree, done in the traditional way, they were relieved and delighted. A woman from Bangalore had come recently, wanting kasuti on cushions, and she was a Hindu at that… How different their creative integrity was from the canny Kutchi women who’d happily embroider Mickey Mouse as long as someone paid them! Designs were a problem. Women in one village knew one motif, those in a village a few miles away another. How to combine them and teach the women more designs? Kasuti is done by counting threads, not by transfers or stamping out motifs onto the cloth. I decided to document the various patterns. Finding graph paper and a un-smudgy photostat machine in Dharwad in the early 80’s wasn’t easy! The women were generous and trusting, lending me their various precious bits - some done by their grandmothers and falling to pieces - often so stained and faded it was difficult to decipher the design. One had been done as a present for Indira Gandhi, but in the end she’d never come to that village. Eventually, working through several sleepless nights, I had over a hundred different negi, gavanti, murgi and methi border, pallav, buti and all over motifs, numbered, photostatted and coded. Colourways were similarly codified. The women loved having their own little design manuals and discovering new combinations of stitches. They were surprised by and not at all admiring of my colour sense - they couldn’t understand my aversion to the peacock blue, acid yellow and florescent pink chemical colours they adored. But they were thrilled to see their familiar red bordered Irikil sarees re-coloured and eventually began to quite like the embroidery shades too. 15 years later, the story of kasuti is both a success and a failure. The kasuti sarees and dupattas came to DASTKAR in Delhi and were an instant sellout. But their supply is a trickle not a flood. Kasuti is a slow, labour-intensive embroidery and the women remain retiring perfectionists; reluctant to commercialise their craft into a regular production system - whatever the earnings it might bring them. I respect them for that and try not to push them. Sadly, Mukund Maigur, the earnest young crusader who first introduced me to the kasuti and Irikil craftspeople, has succumbed to the Indian system. The pressures of marriage and a family led him into debt and corruption. He owes us money too, and we don’t speak now, but occasionally we pass each other on the Dharwad streets - it brings back our journeys, our dreams and our adventures. This article was originally written for the Diplomatic Corps in July 1997 |

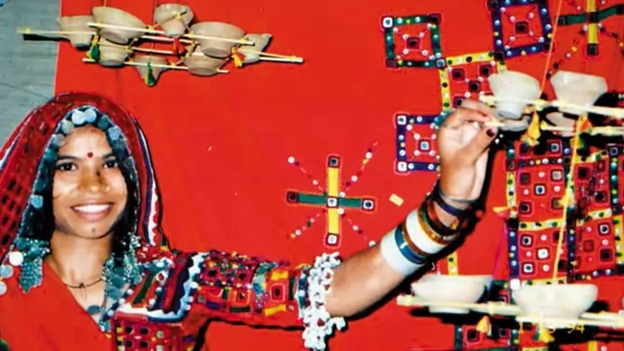

India is good at creating caste systems: from age-old prejudices of birth, community, and gender coexisting with newly coined ones born out of education, wealth, power and privilege. While old prejudices lose their rigid hold, new ones keep emerging—urban/rural, English speaking/vernacular speaking, literate/illiterate, down to the colour of one’s skin. Additionally, parental ambition and prejudice downgrade the educational advantages of liberal arts versus science and technology. One serious consequence is positioning highly skilled traditional craftspeople on the lowest rung of the professional ladder. It’s Stockholm airport in Sweden, and Shanta, 23 years old and the youngest ever craftsperson to win the Master Craftsperson Award for her tribal embroidery, stands on top of an escalator for the first time in her life. She has flown in a plane, exhibited a major new work at one of Europe’s premier art museums, danced with international artists, and lectured at Sweden’s Boras Design School, becoming the first Lambani to travel abroad. “Isn’t there a World Cup for Embroidery?” she asks. “I’m going to win it!” Why not? Embroidery should be given due recognition—as a creative art as well as a competitive career opportunity. Elsewhere, Chandra Bhushan and Irfan Khatri are two young men with totally different skill sets and backgrounds, coming from different communities and areas of India. One is a Brahmin folk artist from Bihar, the other, a Muslim block printer from Kutch. But they share common, important links—they are both craftspeople, and have both received the prestigious National Master Craftsperson Award in 2005. More significantly, both Bhushan and Khatri, like Shanta, are successfully practising craft as an ‘economic’ rather than a ‘cultural’ activity, at a time when many young craftspeople are leaving the sector in search of other more lucrative careers and stable employment.

Righteous Pride: Shanta Bai, a Lambani embroiderer and the youngest ever National Master Craftsperson awardee Photo: Laila Tyabji—Dastkar

Craft and craftspeople are in a curious position today—one of both strengths and weaknesses. On the one hand, markets and consumerism are growing, with affluent upwardly mobile lifestyles creating new demands and opportunities; on the other, the new middle class, especially the young, are getting more into branded Western labels and 21st century professions. Craft is looked at as boring, primitive, passé. This is shortsighted. One of India’s major advantages is that we have our feet in both the East and the West, and have not lost our traditions, culture, and arts in the process of acquiring new aptitudes like English education or information technology. Sadly, we don’t realise it, or where it can take us in the future. At a time when the rest of the world mourns its lost handcraft traditions and celebrates its few remaining makers, artisans in India are anonymous, uncredited and under-valued.

The intricacy, design skills and mathematical precision required to create a double ikat warp and weft or the taleem notations for a jaamdani shawl is considered vastly inferior to programming computer software, just as a master weaver would be considered a most unwelcome son-in-law for a middle-class mother.

Contemporary Indians get terribly excited when an Indian enters space, wins Miss Universe, or gets a medal at the Olympics. But few appreciate our unique distinction in having literally millions of existing master craftspeople practising skills that are no longer extant in the rest of the world. It is foreigners, whether tourists, merchandisers, or designers, who realise that India’s living crafts traditions are not only a tourist attraction, but have a huge long-term commercial potential as well.

We in India need to be aware of this gold mine, rather than let others exploit it. If we want to capture the world, we have to do it on the basis of our strengths not our weaknesses. And one of our strengths is our distinctive aesthetic and knowledge systems. Not just the materials, motifs, and techniques, but the unique ways in which traditional communities look at things and problem-solve, use waste, take from the environment and give back to it.

Ironically, worldwide post-Covid recession and growing environmental concerns can be an opportunity for India! People looking for cheaper green alternatives to expensively mass-produced goods are rediscovering the beauty, utility and variety of indigenous handcrafted products: a mirrorwork jhola instead of a Gucci bag, embroidered juthis instead of Louboutin heels, a hand-painted Madhubani T shirt instead of a Benetton one, moda chairs and woven durries—the folk art that inspired the likes of Jamini Roy and M.F. Hussain.

Craft, In Both Practice And Theory, Can Be A Powerful Tool Of Emotional, Economic And Intellectual Empowerment For Children At All Levels, Locations And Sectors.

The craft sector with its millions of craftspeople practicing every kind of unique tradition, in every possible material and medium—from terracotta to gold, from metal casting to intricate embroidery—is a wonderful career opportunity for the young who want a life that is creative, fulfilling, and also economically rewarding. Whether you are a designer, a development consultant, an architect, a social anthropologist or photographer; an entrepreneur, retailer or exporter; craft offers career options that are challenging, varied, and different. If your goal is to see your creations on the fashion ramp in Paris or New York, using Indian textiles and craft is an obvious way to stand out. If your ambition is to build a business, any of the many forms of handcraft production is one area that doesn’t require energy, machinery, a huge and expensive infrastructure, or training of your work force. Even raw materials are locally available! And any academic or novelist would have a fascinating lode to mine in the story of Indian crafts and the people who craft it.

As more and more people move to the cities, and education is increasingly geared to developing professional expertise with an international corporate potential, we need to ensure that schools and colleges inculcate an awareness of India’s own values and skills. And the power and potential that lie within them. This needs to be done in a manner that is creative and fun—not as boring and irrelevant history. It should link up with everyday life and the other professional expertise that students acquire.

Craft, in both practice and theory, can be a powerful tool of emotional, economic and intellectual empowerment for children at all levels, locations and sectors of school and society.

Learning about craft, and working with craft techniques and materials can give you an appreciation of the relationship between you and your environment, and the inter-dependence of the two. It teaches you hand-eye coordination, the use of materials and the importance of making from scratch. It has the potential to teach you tolerance, understanding and appreciation of difference. It is a means of enriching your world as well as giving you information processing skills: showing you how to locate and collect relevant information, compare, contrast, and analyse relations between the whole and a part.

Craft education can also build in the child ‘enquiry skills’ which involve asking questions, planning activities; improving ideas that go hand-in-hand with creative skills—expressing oneself artistically, exploring different ways of personal expression along with involvement in school projects and with business. Lastly, it can equip you with valuable entrepreneurial skills that allow you to enjoy change, practice risk management and learn from mistakes.

The process should start at play-school and continue through the learning process of each student, remaining an integral part of their psyche and ethos throughout their lives; affecting how they look at history, society, culture, economics and art. Craft is not an old-fashioned ‘hobby’ but a vital entry point to India’s past, present and future. Like other liberal arts, it can lead to a discovery of oneself and one’s life directions.

Craft is not just for Shanta, Chandra Bhushan and Irfan Khatri, who have inherited craft skills from their ancestors. Nor should the choice be either/or technology or tradition, arts or sciences, rural or urban. Each has its place and purpose, and a synthesis of both would create an exciting and necessary dynamic, opening up new avenues, new careers and a new India.

Righteous Pride: Shanta Bai, a Lambani embroiderer and the youngest ever National Master Craftsperson awardee Photo: Laila Tyabji—Dastkar

Craft and craftspeople are in a curious position today—one of both strengths and weaknesses. On the one hand, markets and consumerism are growing, with affluent upwardly mobile lifestyles creating new demands and opportunities; on the other, the new middle class, especially the young, are getting more into branded Western labels and 21st century professions. Craft is looked at as boring, primitive, passé. This is shortsighted. One of India’s major advantages is that we have our feet in both the East and the West, and have not lost our traditions, culture, and arts in the process of acquiring new aptitudes like English education or information technology. Sadly, we don’t realise it, or where it can take us in the future. At a time when the rest of the world mourns its lost handcraft traditions and celebrates its few remaining makers, artisans in India are anonymous, uncredited and under-valued.

The intricacy, design skills and mathematical precision required to create a double ikat warp and weft or the taleem notations for a jaamdani shawl is considered vastly inferior to programming computer software, just as a master weaver would be considered a most unwelcome son-in-law for a middle-class mother.

Contemporary Indians get terribly excited when an Indian enters space, wins Miss Universe, or gets a medal at the Olympics. But few appreciate our unique distinction in having literally millions of existing master craftspeople practising skills that are no longer extant in the rest of the world. It is foreigners, whether tourists, merchandisers, or designers, who realise that India’s living crafts traditions are not only a tourist attraction, but have a huge long-term commercial potential as well.

We in India need to be aware of this gold mine, rather than let others exploit it. If we want to capture the world, we have to do it on the basis of our strengths not our weaknesses. And one of our strengths is our distinctive aesthetic and knowledge systems. Not just the materials, motifs, and techniques, but the unique ways in which traditional communities look at things and problem-solve, use waste, take from the environment and give back to it.

Ironically, worldwide post-Covid recession and growing environmental concerns can be an opportunity for India! People looking for cheaper green alternatives to expensively mass-produced goods are rediscovering the beauty, utility and variety of indigenous handcrafted products: a mirrorwork jhola instead of a Gucci bag, embroidered juthis instead of Louboutin heels, a hand-painted Madhubani T shirt instead of a Benetton one, moda chairs and woven durries—the folk art that inspired the likes of Jamini Roy and M.F. Hussain.

Craft, In Both Practice And Theory, Can Be A Powerful Tool Of Emotional, Economic And Intellectual Empowerment For Children At All Levels, Locations And Sectors.

The craft sector with its millions of craftspeople practicing every kind of unique tradition, in every possible material and medium—from terracotta to gold, from metal casting to intricate embroidery—is a wonderful career opportunity for the young who want a life that is creative, fulfilling, and also economically rewarding. Whether you are a designer, a development consultant, an architect, a social anthropologist or photographer; an entrepreneur, retailer or exporter; craft offers career options that are challenging, varied, and different. If your goal is to see your creations on the fashion ramp in Paris or New York, using Indian textiles and craft is an obvious way to stand out. If your ambition is to build a business, any of the many forms of handcraft production is one area that doesn’t require energy, machinery, a huge and expensive infrastructure, or training of your work force. Even raw materials are locally available! And any academic or novelist would have a fascinating lode to mine in the story of Indian crafts and the people who craft it.

As more and more people move to the cities, and education is increasingly geared to developing professional expertise with an international corporate potential, we need to ensure that schools and colleges inculcate an awareness of India’s own values and skills. And the power and potential that lie within them. This needs to be done in a manner that is creative and fun—not as boring and irrelevant history. It should link up with everyday life and the other professional expertise that students acquire.

Craft, in both practice and theory, can be a powerful tool of emotional, economic and intellectual empowerment for children at all levels, locations and sectors of school and society.

Learning about craft, and working with craft techniques and materials can give you an appreciation of the relationship between you and your environment, and the inter-dependence of the two. It teaches you hand-eye coordination, the use of materials and the importance of making from scratch. It has the potential to teach you tolerance, understanding and appreciation of difference. It is a means of enriching your world as well as giving you information processing skills: showing you how to locate and collect relevant information, compare, contrast, and analyse relations between the whole and a part.

Craft education can also build in the child ‘enquiry skills’ which involve asking questions, planning activities; improving ideas that go hand-in-hand with creative skills—expressing oneself artistically, exploring different ways of personal expression along with involvement in school projects and with business. Lastly, it can equip you with valuable entrepreneurial skills that allow you to enjoy change, practice risk management and learn from mistakes.

The process should start at play-school and continue through the learning process of each student, remaining an integral part of their psyche and ethos throughout their lives; affecting how they look at history, society, culture, economics and art. Craft is not an old-fashioned ‘hobby’ but a vital entry point to India’s past, present and future. Like other liberal arts, it can lead to a discovery of oneself and one’s life directions.

Craft is not just for Shanta, Chandra Bhushan and Irfan Khatri, who have inherited craft skills from their ancestors. Nor should the choice be either/or technology or tradition, arts or sciences, rural or urban. Each has its place and purpose, and a synthesis of both would create an exciting and necessary dynamic, opening up new avenues, new careers and a new India.

| Ashoke Chatterjee was executive director of National Institute of Design (NID) from 1975-85, Senior Faculty Advisor for Design Management and Communication from 1985 to 1995, and Distinguished Fellow at NID from 1995 until retirement in 2001. He has served for many years as honorary president of the Crafts Council of India and continues to work as a consultant in India and internationally, especially on projects concerned with water management and environmental issues. After more than ten years as international advisor, in 2000 Ashoke Chatterjee joined the board of directors of Aid to Artisans, a US based non-profit organization that offers practical assistance to artisans worldwide. NID in Ahmedabad is internationally recognized as one of the foremost institutions in the field of design education, research and training. In 1975, NID was asked to be involved with the Rural University, a new concept in education and rural development initiated by Professor Ravi Matthai, first director of the Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Ahmedabad. Ashoke Chatterjee became part of the Rural University team that worked with people of the Jawaja block, which included about 200 villages with a population of approximately 80,000 people in a drought and flood prone district of Rajasthan. The Jawaja project was an educational experiment-in-action based on the idea that development activities must be a vehicle for learning. Although the Indian government designated Jawaja as a region of high poverty and no resources, some people were knowledgeable of spinning and weaving and there were a few looms. Weaving and leatherwork became the basis for economic development activities, and through the participation of its designers, NID tested the relevancy of bringing design education into this rural context. This interview, recorded in October 1997 at NID, focused on the story of Jawaja. Any changes or developments that have occurred, particularly at Jawaja, since the time of the interview have not been included in this account. Interview CJ Looking back over the many years of your involvement in craft development, what stands out as a significant experience? AC The most seminal experience has been Jawaja. At the time NID was debating the relevance of design and looking at crafts in terms of the challenges of development: the transitions taking place, the potential and complexity of this sector. Craft is not a homogeneous area. It is about hand skills but it is full of diversity and contradictions. Jawaja, however, was quite removed from all the discussions about tradition, culture, and preservation of all that. Jawaja was a life and death situation. As a country we have inadequately addressed the issues of craft. We try to intervene in different parts but we have not looked at craft in an integrated, holistic way. The Jawaja project was one circumstance, which integrated many aspects of craft: heritage, culture, social structure, design vocabulary and NID's design inheritance. But Jawaja was not a craft project; it was development defined as self-reliance for those who have been the most dependent in our society. Ravi Matthai explained self-reliance this way: Can people do something for themselves tomorrow that today others should be doing for them, or are doing for them and they should be released of that dependence? Ultimately, Jawaja taught us that the whole is about people and you have to attend to people first and last or else nothing you do will be sustained. Although it was not the intention, we took the craft route and through this we were able to demonstrate what an enormous force the crafts can be in this country. Craft is the strength inherent in our people. They know what they do with their hands and there needs to be a market for what they make. The move towards self-reliance forced us to tap the considerable design energies of the community. We went to Jawaja being told that there were no resources, but we found people with an extremely strong understanding of design and an ability to innovate their own designs. We took the route to create craft products that the local power structure, the moneylenders, knew nothing about. It was not an option to make traditional products to sell in markets controlled by the power structure. This route had to be bypassed. To exercise this option they could not make colourful juttis and footwear that were in the control of the people they were trying to escape from; they began to serve a market that the power structure had no control over. Now they have become a part of the power structure. And the women's groups are doing embroidery applied to the leather and making richly embroidered diary covers. There has been tremendous interaction between designers and craftspeople at Jawaja and the designers worked within certain constraints. The designs had to be what the weavers could understand, respond to, modify and develop. If the weavers were just sent a design, they would be in no position to take ownership and we were keen that they have design ownership. We also encouraged them to interact with buyers. So there was considerable discussion of what the people of Jawaja felt would be suitable. For example, craftspeople knew they had to modify their designs in response to a particular market, the dyes and weaves they knew best, the available raw materials, and cost implications. Design diversification happened within this constraint because the idea was to make the design process understandable and manageable by the craftspeople. In terms of designs that have emerged, it is not easy to say which designs are theirs and which are ours and which come from buyers. Some critics of the Jawaja project believed we were not tapping the traditional strength and products of Rajasthani craftsmen. Early on, critics said the designs were Scandinavian because one of the original designers was from Finland and they assumed she was intervening and imposing. But the floor coverings emerging from Jawaja with strong earth colours and simple geometrical designs came from the craftspeople, whose environment inspired them. They produced a simple design which they could do in various colour ways in response to a market. CJ How did people at IIM and NID conceptualize the Jawaja project? AC It started over twenty years ago with a desire to see whether there was anything that institutions like IIM and NID knew that could be relevant to this country at the very gut level of problem solving, the level of hunger, poverty and deprivation. Most of our institutions skirt this issue because we tend to gravitate towards the more organized Indias who have enormous needs and who respond to us quickly. At the outset, Ravi Matthai said to us at NID, if you are worried about the relevance of design in India, come along. We don't know what will happen here. Join the team. The intention was to look at how do we make education relevant. How do we test management skills in this area? How do we transfer skills in management to a rural community in order for them to be able to manage their affairs? When Prof. Matthai looked for a space for an educational experiment he found hostility in every village towards schools. Schools were seen as totally irrelevant and a factor for alienation because they had nothing to do with gut issues that these communities were dealing with. Much of the dialogue at Jawaja began with schoolteachers: What do you think this place has? What are the needs? So teachers became the first resource persons. And two schoolteachers became very important because they provided the vision and insight and the bridge to the community. They were trusted. They began to articulate what they thought this community was capable of. They also began to understand what the external institutions had to offer and they were important in making the link. They became local leaders. The first reaction of NID students and teachers who went to Jawaja was a sense of guilt and a response of charity. They said the issue was not about design but about sending people food, clothing, doctors and medicine. We had to deal with that. It is a difficult place to work emotionally and one does get very emotionally involved with this community. CJ How do you compare Jawaja now to what was happening 15 to 20 years ago? AC 15 to 20 years ago craftspeople of Jawaja had no ability to deal with the external market. There was no capacity to understand the needs of buyers far removed from them physically, socially, emotionally, and psychologically. That gap was huge. They felt inadequate and that they needed to wait until someone told them what to do. In those days they couldn't enter the Taj Hotel in Bombay to have direct contact with a buyer. Now they are no longer thrown out of the Taj Hotel. They have travelled widely and they have developed street smarts to be able to cope. Now their products have gained an international reputation, not just occasional local exposure. OXFAM, just one of their international buyers, has sold their crafts for almost 15 years. This is a huge accomplishment for this community. They have learned through all the ups and downs to satisfy a buyer far away, and to understand what this means in terms of their own vision. Many of these people had never been to Jaipur. Some had not been to Ajmer only 40 minutes away. And now because London is a place they deal with they can say, we don't think it is fair that the buyer in London has rejected this product. Earlier in the project we imposed on the craftspeople an obligation of training others. Since a principle of the Jawaja project was that nothing would be free, they were required to teach in another village what they had been taught. This was not easy. They crossed caste barriers and encountered social problems. One man said he couldn't undertake training with certain villages where he was not on speaking terms with some people. NID said find a way of training without speaking. After teaching without speaking and realizing the absurdity of the situation, they re-established a cordial relationship. Now the craftspeople have become part of a training program for income generation capacity building at the rural level in the state of Rajasthan. Many of the weavers and leather workers are recognized trainers who go out to various parts of Rajasthan and provide training to other groups. NID has also recommended that the Jawaja community be part of the Institute of Crafts, being set up in Jaipur. They could become trainers and this would also give them status and recognition. A major challenge today is their own internal capacity for working together and decision making in difficult situations, such as quality control. They don't have a mutually accepted standard of quality for people to measure up to and sometimes they put sub-quality materials with good quality materials in a shipment. Or there are pressures to accept quality that is not top class. In addition, they need to take on the discipline of bank loans and repayment of bank loans. They would rather have an external agency do the difficult work of dealing with people who default on bank loans. It is difficult to summarize where they are now. The people of Jawaja are now self-reliant over many things for which they were totally dependent in the past. But what right did we have to expect this community to be totally self-reliant? They still don't have adequate drinking water, adequate sewage sanitation, or education. The health facilities are terrible. At NID we realize that after 20 years we are also not self-reliant. We are battling with a government that is now reducing their grants to us. Constantly, in development projects, we expect things to happen at the village and grass roots level that we never expect at our own level. We take our own dependency as part of a normal social and political structure. Today the Jawaja craftspeople are very dependent on outside support for marketing. And the major cause for their dependence is that marketing for the entire craft sector in India has been tragically neglected. Marketing in India is a complicated scene for Proctor & Gamble and Macdonalds, let alone for a group of artisans. And those companies have advertising agencies, banks and consultants. Artisans are a group of people who have none of that infrastructure and we expect them to be self-reliant, when nobody else is! No one from IIM is involved today. After Prof. Matthai died suddenly in England due to illness, Prof. Rajiv Gupta, a colleague at IIM took over the Jawaja Project until his retirement. But this project continues to require emotional and physical stamina. You cannot cut yourself off like you can from other clients. There is never a point where everything is done for them. It is always an ever-widening circle of problems. They keep saying, tell us what we should do. And we say, no, tell us what you think you want to do. And they get impatient with us. Basically the whole issue is how can we help them develop their own problem solving skills. And there are many things that this project did not address: the problems of women, problems of health, and the scarcity of drinking water. There is a whole range of issues that need attention, which our project has not been able to attend. CJ How has the Jawaja project changed your view of what is possible in regard to the continuity of crafts? AC In my own work with the Crafts Council and other groups I say, respect the aspects of culture and traditions that we have long associated with crafts, but also ensure that the social-economic situation of the people is put at the top of the agenda. Jawaja provided a benchmark in crafts: first focus on and understand the community before we intervene in crafts. Who are the people? What are their earnings? What are their aspirations? What is in it for them? Before we start giving people lectures about their ancient traditions, ask what's in it for them to stay in the tradition? In the case of Jawaja, many of the heritage problems for leather workers were things they wanted to run away from. Their caste elders told them they must not be identified as leather workers; they must have some other identity. When they stopped flaying animals they were left stranded without an identity. We now usually look at tradition and heredity as some exquisite artefact, but for them it was centuries-old discrimination. These things are not easy to look at. In the Crafts Council we have tried to ask what can we do to encourage someone who wants to stay within the tradition? Not force them into it, not make it a kind of a burden. But consider what can be done to encourage any young people who want to remain in the tradition and ensure that their staying in this craft is not at the cost of their own progress as human beings, but rather supplements their progress as human beings. We have also tried in a very modest way to help them with facilities for diversifying and opportunities for income generation. Why should people do crafts full time if they don't want to? Some craftspeople have also become accountants and computer operators. We say, that's fine. Let your child have that option. But don't let them look at the craft tradition and say they have to discard it because it is holding them back; it is a chain. And interventions should not make them think there is something wrong with wanting to shift out of craft. We don't want these communities or individuals to feel like they are museum pieces. They should feel they have an option. Now we are stuck with this great controversy on child labour. We are struggling with how to cope with this issue, because the whole thing of father to son and mother to daughter is part of this honoured and treasured tradition. But we know that we must not close our eyes to exploitation. Exploitation in certain crafts like brassware, glass, the carpet industry is incredibly severe. How does one balance this? How does one create an intelligent understanding among buyers in India and overseas that the issue is that these children must be in school? People need to realize that learning a craft within the family home need not be considered exploitation. It can be a very rich experience. Easy generalizations should be avoided and yet there is no question that exploitation exists. Even in Jawaja the women do half the work involved in craft processes. But do the craftsmen account for that in their costing and pricing? Do they transfer funds to them? How many women members are in the association? None of that is considered. There are huge opportunities for women craftspersons. But people of Jawaja are missing the opportunities. CJ Is there emergent leadership among the women? AC Yes, they have a women's group. We plan to go there soon to see what these women want to do. What kind of products can they make? They probably would like to go into their traditional embroidery and find a market for that. We have not had contact with the women for some time. Although they came to meetings they usually kept quiet. No matter what we did to encourage them, the women were silent and the men did all the talking. So the women's group is a modest step that could have huge implications. CJ Do you think that new meanings will be associated with craft activity? From my point of view, meanings are inherent in a process of making something, whether these are cultural, mythological, or personal meanings. Meanings also shift because of many influences. AC The need for a shift of meaning has been with us from the beginning. I think those products from Jawaja have come to mean a sense of freedom, of true freedom. Not a freedom achieved but perhaps a freedom achievable. Demonstrated. Experienced. Real. And something for which other people cannot take the credit. NID cannot take the credit for what they have done. Their products demonstrate a context that is theirs and under their control. The potential is huge. Another strong sense of meaning, which their traditional products would not have given them is that they are part of a team.. We kept saying this is all about networking and building teams. We work as a team. You have a right to use institutions like NID and ask for services. What we have not researched is the psychological and social impact on two generations of people in Jawaja. A generation has grown up for twenty years within this context. What has it meant to the young people that their parents were part of this experiment? What has it changed for them? One man said, "Everything has changed for my son." Well, what has changed for his son? What does it mean for his wife who is now a member of the Jawaja association? We don't know what stories they are telling in their own community. CJ What are some of the implications that have come from the way things were done in Jawaja? AC It sensitized us in ways that we learned to ask questions that we were not raising before. We learned that first you have to ask: What do the people know that you should know before you even start asking questions? We also learned to ask: Do the people have some concept of tomorrow? If they don't, then development is meaningless. Because in Jawaja they didn't, their concern is survival, today. These people don't want to hear about other things because whatever you say, they will listen patiently, and when you leave they will be left where they were. We learned to ask: Have we paused to reflect on what aspirations these people have? Are they the same as ours? Do they want to go where we think they ought to go? Others do not bother to find out what the people feel, what they aspire to. Or if they have, it is a superficial nod towards participation. In Jawaja, we asked people what they needed and they told us. Rather than throwing posters at people, we asked whether they could communicate in their own way, at their own level, in their own India, because that would give them a lasting communication resource. But very often project co-ordinators and donors want to know how many flipbooks or videos have been made. They won't ask how many people are standing on their own feet as a result of something you have done. The same with Jawaja, donors ask how many people have you made self-reliant? Where are the figures? Well, we don't know and we haven't any statistics. But what is the value of one person made self-reliant? Some people refuse to discuss it on these terms, but we push a bit further, saying, if that person was you or your child we would never say that's a foolish thing to have done. If we value each other as individuals then maybe we can say something significant has taken place. When we started working in this field, we learned that the so-called development world is preoccupied with success stories, and donors want to replicate the experience. But they are usually looking for the wrong things. Learning doesn't take place in neat little project timetables. People and communities cannot be replicated, but learning can be extended. You learn more from failure than you do from success. And only the next generation will see whether we have succeeded or failed. I wish our intervention could have been better sustained in many ways. Somehow, compared to the need there, what we have done seems so little. But there are ripples. The educational process of the Jawaja experience transformed many people. One of the schoolteachers is now the head of a major NGO in Jawaja involved in greening that part of the desert. Students at NID were influenced enormously by involvement with Jawaja. All of us who were part of that team have gone on to do other things. The Scandinavian textile designer later applied this learning in Lapland and Finland. Another person went on to head a society for the promotion of wasteland development, and is now working for the World Wildlife Fund. One of the first volunteers at Jawaja is now an eminent professor of macro-economics at the Madras Institute of Development Studies. He said, I wouldn't be where I am today if it wasn't for Jawaja. This is the single most important learning that I've taken and applied to everything that I've done. Personally, I have applied this learning in all the work I have done in communications in India, Pakistan, Columbia or Zimbabwe. I think I would not have been able to do any of that work without having gone through Jawaja. For NID and IIM, Jawaja is the only deprived community we have served without a break for 20 years. It is such a wealth of knowledge and experience. When our colleagues from Jawaja join a discussion the whole quality of the discussion transforms because they bring insights and opinions, which are far removed from what we know. Although we are physically in the same country, we are almost from another universe. Numerically the Jawaja project remains small but the craftspeople have enormous capacities and some have gone on to become entrepreneurs or join other enterprises, others have gone back into agriculture, but they take with them new knowledge and capacities. They are known in craft circles; they have been seen and heard. Attitudes and the language used have changed enormously due to this interaction. The people of Jawaja have gone far as individuals and as a community and they are reputed as craftspeople throughout this country. When they walk into a Crafts Council meeting, they are respected and looked upon as the wise. Other people say, we are having this problem in Andhra or in Manipur; how shall we do it? To me this is very important because you come back to the fact that we who intervened are not the great resource people, they are. The author acknowledges the financial assistance of the Government of India through the India Studies Programme of the Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute. This paper was published in March 2003 in Seminar 523: Celebrating Crafts. Interview by Carolyn Jongeward October 20, 1997 National Institute of Design, Ahmadabad, India. Revised text: August 26, 2002 |

|

“Design” is the new catch phrase among customers, retail storeowners, importers and now even artisans. The market for innovative design was once cornered by high-end retail boutiques in major metropolises but has now expanded to touch consumers both young and old. High school students now know the names of the latest handbag designers and beg their parents for originals that can cost hundreds of dollars. Even large department stores, once relegated to a status more shrouded by the concept of convenience than fashion, are focused on bringing affordable design to the masses. Some of these stores are even delving into issues of fair trade and handmade items, using good design to sell higher priced products. In the world of craft, high design, handmade products have been the recent push among craft innovators the world round. Designers that show in some of the most well known, and most expensive, shops in Paris, London and New York are looking to artisans for production, and even inspiration. Fashion magazines, high-end mail order catalogs and even TV advertisements have begun highlighting or featuring high design craft. Handmade products have turned from tourist trinkets to tailor made fashion. However, the emphasis on cutting edge design and innovation has taken some of the emphasis off of the traditional aspects of craft. Craft supporters have been drawn to handmade products over the years for many reasons. Artisans are often the bearers of culture who pass traditions, both visual and otherwise, down from one generation to the next. These culturally specific traditions are embedded in the motifs, colors and patterns of their embroidery, ceramics or weaves. Artisans have also played other traditional roles in their local communities relating to both agriculture and religion. An artisan’s skills in blacksmithing, for example, would be used to mend plows as well as create craft. In many cultures artisans also play a role in local religions by creating special images, icons and statues that are used for holidays or everyday worship. So, does sleek modern design and merchandised US retail stores take away some of the cultural significance of craft? Should craft advocators focus on bringing handmade products into the main stream market through design or through awareness? These are the questions that I’ve begun to ask in a pursuit of using craft both as a mean of economic development as well as a bridge to cross-cultural understanding. As a way to poverty alleviation, market driven craft, with a base in targeted design, is undoubtedly the necessity for success. High design has brought artisans from poverty to market players and has sometimes brought craft from the edge of extension to the spotlight of the runway. However, what we as craft advocators need to be weary of is the loss of cultural value in handmade goods that can come from homogenized marketplaces in the globalized world. The concept of high design craft needs to be coupled with public awareness and education about the cultural significance that craft can carry. Without this awareness craft can be relegated into the world of one-way globalization, where consumer products lack meaningful cultural weight as they cross borders and market boundaries. |

|

Well after a few months delving into the craft, landscape and culture of Tajikistan, I wanted to return to a topic both familiar and exotic to me. Although I have been studying craft for about four years now, most of my investigation has been focused on India and other international crafts. Other than the occasional craft museum visit or magazine article, I have spent little time truly looking at the American craft tradition. And even further, I have yet to open my eyes to the rich craft traditions sitting on my doorstep. For about the past two years I have worked in Connecticut, but with my attention solely on international crafts I hadn’t bothered to merely open my eyes to the traditions of America contained within Connecticut craft traditions. So upon opening my eyes this month to lead a brief investigation I was surprised to find a healthy contemporary craft scene providing both an outlet for creativity and a source of income for Connecticut artisans. Being positioned in the Northeast coast, Connecticut was a seat of much of early American history. Along with being the fifth state to sign the American constitution, it is home to such American items as the first public library, the first hamburger, the first Frisbee and the first lollipop, as well as some other greats like the first Ph.D. and the artificial heart. And contemporary Connecticut artisans have carried on this great tradition of innovation and today fill-up the galleries and museums line both historic and new towns throughout the state. A few of these artisans were recently highlighted in a Connecticut Cultural and Special Events Guide published by the Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism. Some of the artisans that piqued my interest included Kari Lonning, a contemporary basket maker. Kari, a world renown weaver, creates colorful and intricate baskets that call to mind images of Southern Africa. (http/www.karilonning.com) Kari also works with experimental sculptures and has authored a book on the art of basketry. Her baskets are evocative of both the traditions of Africa and the trends of contemporary America, linking together the geometric patterns with bright funky colors and styles. Ted Esselstyn, another vibrant Connecticut artisan, creates whimsical wooden sculptures, furniture and public installations throughout the state. His pieces are colorful and imaginative, taking ordinary functional furniture and walls to new levels. (http:/tedesselstyn.com) Ted’s brilliant murals and functional sculptures bring the imaginations and dreams of children to life. Some of Ted’s creations are aptly installed in children’s museums, hospitals and libraries. On the other end of the whimsical spectrum is Ann Mallory who creates more stoic images that focus on form and shape highlight the sensuality of objects. Ann’s ceramic and multi-media objects are both beautiful and somber, reminding the viewer that even ordinary objects have depth and meaning. Ann also creates Contemplation vessels from ceramic and bronze. These vessels, textured ceramic pieces, suggest a sense that is both inviting through their size and texture and isolating through their sealed off openings. Although Connecticut is host to a number of rich histories in American aesthetic traditions including quilting, wood working, basket making, embroidery and more, contemporary New England artisans have carried these traditions into the modern economy and society. These artisans still draw heavily on the same inspirations as early American artisans and still use some of the same media and techniques. Aside from the few artisans that I mention only briefly above there are many more contemporary American artisans that continue creating in the traditions of the American past, conveying stories and composing history with every stitch, wood shaving and woven reed. |

|

Background As part of the Disaster Management and Emergency Relief Operations in Kutch, post the January 2001 earthquake, CARE India and FICCI adopted 30 villages in three blocks of Anjar, Bhachau & Rapar in Kutch, Gujarat. They were committed to a broad based intervention that included areas such as health, housing, education and sustainable livelihood. They approached National Intitiute Fashion Technology, New Delhi to develop a comprehensive livelihood package for the artisans affected by earthquake in these areas. Prof. Jatin Bhatt, Head of Accessory Design at NIFT visited the area twice along with Mr. Vipin Sharma, Director, Sead, CARE and his team to evaluate and identify the blocks and villages, based on a number of factors such as accessibility, responsiveness, socio economic climate and available skills and experience of the community. Reality did not always match expectations. Expecting to find over 200 potters in the surrounding villages, it was found the numbers had dwindled to 60-70 artisans, with pottery rapidly disappearing as a craft and means of livelihood. |

||

|

The choices Many individuals and organisations, including NGOs, were working in the areasalready had their hands full with enormous commitments in the process of rehabilitation. NIFT set up its site office with fulltime field coordinators and involved Ms. Vijayalaxmi Kotak, who has possibly one of the longest association and experience with Kutch artisans through her Gurjari assignment, to enhance effective community mobilization. |

||

|

Not wanting to enter a sector where enough work was being done, NIFT consciously chose not to restrict work with embroidery and textiles, inspite of easy access to a large population base practicing the craft as a part of their daily lives. Interestingly, some of Rabaris communities with distinctive style of embroidery, even today travel upto Surat and Balsar to graze their camels over six months in a year. Instead they opted to work in other craft areas of pottery and knife making with some amount of embroidery crafts with the Rabaris and Ahirs. |

|

|

|

For logistical reasons finally, four villages namely Jharu, Chandrani, Khedoi and Ratnal in the Anjar block each within a reasonable distance from the other and Nana Reha, a village close to Anjar and known for its knife making over a century, were chosen to be the focus of the project. |

||

|

The Implementation of the Programme What emerged was a concrete plan to involve the artisan at every step in the process of creating and retailing a craft product. Six faculty members along with the active involvement of the technical assistant as well as staff of the Accessory Design Dept. at NIFT committed a period of six months to the project, beginning May 2001. |

||

| The NIFT team led by Prof. Jatin Bhatt had Mr. M.S. Farooqi, Mr. V.Ameresh Babu, Mr. Arvind Merchant and Mr. Sanjeev Kumar as the think tank. Equally responsible for field operations they were supported by Mr. Ashuthosh Porus, Junior Faculty and Mr. Abhishek Pratap Singh, student of Accessory Design. The project structure also provided twenty nine senior students to carry out the Design and Product Development component of the project on field for over six weeks in the above mentioned villages. Prior to this, the NIFT faculty team with artisans from the selected craft sectors developed specific project strategies concerning critical areas of process ntervention. The faculty team with was primarily responsible for developing specific brief for students and artisans to ensure meaningful and contextual outcome from this very brief but intensive interaction of six weeks under their direct guidance and supervision. |

|

|

|

At the first stage of programme implementation, twenty-five artisans from Kutch visited Delhi and surrounding areas for a period two weeks to orient them to urban markets and consumer preferences. As part of their orientation they interacted with other artisans and industries creating similar products with similar raw materials using different techniques and technologies. |

||

|

Their Experiences Separate teams worked with the Muslim knife makers of Nana Reha, the Muslim potters of Khedoi and Chandrani and Rabari and Ahir women of Jharu, Ratnal and Chandrani, who did embroidery and patchwork on accessories. These teams were confident about the skill, experience and knowledge of the artisans. What they wanted to introduce was the element of design development as a part of the process based implementation, keeping in mind the community culture and capabilities, the ability to look at a product and develop it according to its specifications. In all cases at the first stage, the artisans were made aware of the concept and importance of consistency including precision in dimensions and measurement. |

||

|

Involving potters from Uttam Nagar, New Delhi the Anjar potters were introduced to newer, efficient yet low cost technologies, such as kilns. Until then the potter community had used open pits for firing. The use of a kiln enabled the firing to be completed in a much shorter time and greater fuel efficiency and for the first time the potter community shared a kiln and fired continuously for 12 days around Diwali, which they could not otherwise have done, with an open kiln. Ms. Renuka Savasere, a ceramic designer, got very closely involved in net working and sustained interaction with the artisans over four months as a specialist brought on the project by NIFT. The potters were also introduced to terracotta slip casting techniques and their use, differing methods of clay preparation and improved quality of clay. They also experimented with a different set of aesthetics. For instance, the deliberate creation of perfectly centred pots which were cut into half and joined in a skewed fashion, thereby achieving a more contemporary look for the pots. |

|

|

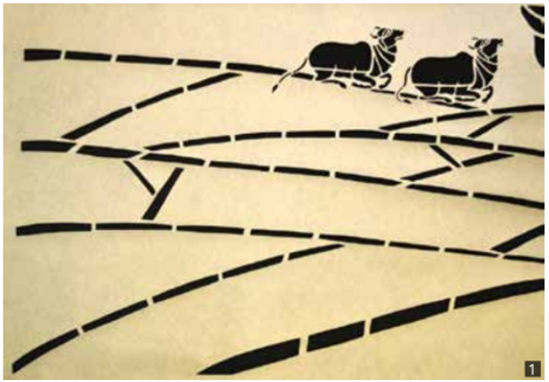

The leverage the artisan possesses is quality and skill. What he needs to know is available technology and information on the whims of the market. This was especially true for the metal workers of Nana Reha, where the entire village is involved in the production of knives such as chakkus or penknives that find their way to different parts of the country. The metal artisans were taken to Moradabad as an example of where a craft can reach and change the equation for an entire town. Contemporary shapes of blades and handles and different alloys were introduced to the artisans. Mr. Jogi Panghaal, who has worked extensively in the area of craft intervention, was involved for over four weeks with the interactive design component between students and artisans to have yet another dimension to the design directions being guided by NIFT faculty. Similarly, expertise was sought for issues on skill and knowledge enhancement pertaining to various processes. |

|

|

Rabari and Ahir women are well known for their exquisite embroidery and patchwork. The designs are intricate and the colours vivid. Working with the NIFT team the artisans realized that they needed to add value to a product, which does not necessarily require more labour and ornamentation. They understand today that embroidery with a single coloured thread may be of more value than a carefully chosen multi coloured pattern or that white embroidery on white cloth or black embroidery on black cloth may actually sell better. That a product from a village could just be in single colour with shade variations, in the urban demand centres. |

||

|

Replying to a question that the artisan was in effect being used as a pair of skilled hands rather than a creative individual – Jatin Bhatt explained that having exposed the artisan to newer products and preferences, the artisan now has the freedom to create across different aesthetics and actually does so. This is also one of the very few instances where design is invested and applied as a larger, holistic process addressing rehabilitation and community mobilization concerns. |

||

|

The questions come naturally to the mind what happened after NIFT left? How successful was the intervention? Has it meant more orders and markets? What did the community gain by the whole programme? In May 2001 the NIFT team was travelling from village to village and artisan area to area. The follow up, in January 2002, saw over 200 artisans gathered in Madhapar exchanging ideas and exploring further possibilities under Design Yatra-2002 over eight days with 30 design students and seven NIFT faculty. CARE India has established a Business Resource Centre for all round management for the next 5 years to support the community and ensure the sustainability of the project. |

|

|

|

Obviously much needs to be done by the community itself. For instance, who decides who gets the fresh orders– the Sarpanch or the whole village? Will it be done on the basis of the skill of the artisan or by rotation? Can the community organise itself in such a way that it takes from each what they are best at? Already the change is visible and the community is talking about it. |

||

|

EMBROIDERY |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

KNIVES |

|

|

|

|

Thirty years ago the Crafts Council of India (CCI) held its 1986 National Meet at Visva-Bharati in Santiniketan, a gesture of respect to a profoundly influential craft ethos. Perhaps CCI was also in search of tranquility in a turbulent year that had altered India’s history: the siege of the Golden Temple and injustice to Shah Bano. Gurudev’s vision of an India unbroken by “narrow domestic walls” seemed then, as now, to be under siege. All these years later, India’s artisans and their crafts are in crisis as well as on the cusp of new opportunities. 2016 saw CCI return to Santiniketan to reflect with that community on the relevance of Tagore’s legacy in such changing times. The experience proved as challenging as it was rich in learning. Artisanal wisdom and skill were central to the vision on which Visva-Bharati, Sriniketan and Shilpa Sadan were founded by Tagore. India’s craft renaissance began there, and then some distance away at Sabarmati Ashram. Dialogue between the Mahatma and Gurudev on India’s craft heritage was an extension of shared concepts of freedom and modernity, and hand production came to play a catalytic role in the struggle for independence. When freedom came, Nehru integrated crafts into development planning, the first demonstration of its kind anywhere. A sunset syndrome To succeeding generations, including activists and craft communities brought together by Kamaladevi Chattophadhyay and others, artisans and craft were as indelible as the tri-colour. About a decade ago, something changed. Craft heritage had become an empty mantra. From high places CCI was told that hand-made products and their makers comprised a “sunset industry”. Indeed, India’s global image of handcraftsmanship had become an embarrassment, akin perhaps to snake charming. Progress was now imaged as Singapore or Silicon Valley. Handicrafts were clearly out of step. So they should fade gently into the night, and artisans turned to contemporary ‘sunrise’ callings that better embrace Silicon Valley aspirations. For craft activists, the shock of these new attitudes was profound. India had demonstrated that its crafts were not just beautiful products, but constituted a strength that had not only helped topple an empire but had then demonstrated a creativity that took India’s aspirations to the world. Acknowledged as the second largest source of Indian livelihood, artisans also represent communities and locations still at the margins of development. To what alternative occupations can these multitudes flock if ‘sunset’ turns to darkness? New technologies have demonstrated models of jobless growth. The IT industry, so ingrained in that Silicon Valley mindset, represents less than 3M jobs. If not food and hand production, what else can India suggest as an immediate path for millions? Against such speculation, a penny dropped. Neither Government nor activists had an accurate idea of the size and economic significance of the sector activists wanted to protect. Without robust data, dismissive attitudes could flourish and disastrous decisions made with impunity. In 2008 the ‘sunset’ syndrome brought CCI and partners together at a Kolkata conclave. There Gopalkrishna Gandhi observed that Government’s heart could only be influenced through Government’s mind. Without economic evidence, all other craft arguments --- social, environmental, cultural, political and even spiritual --- would fail. The immediate task was to demonstrate craft impact on India’s economy. Yet CCI experience had so far been driven by cultural and aesthetic values, not economics. Economists were now needed as partners. Three years followed of research and methodological experimentation in selected locations. Vigorous advocacy of results finally encouraged the national Economic Census 2012 to include artisans and crafts, for the first time ever. “Life in its completeness” While Economic Census numbers are under review, preliminary indications of scale far exceed past official estimates of about 11M artisans. Some calculations reach over 70M, others reaching 200M. Clarity is now expected from a census designed specifically for the hand-production sector. It will go beyond the Economic Census constraint of independent entrepreneurial establishments in the official list of selected crafts. A watershed in sector awareness and action may be ahead. That prospect encourages a re-visit, within a changed India and in another century, of Gurudev’s mission of transformational livelihoods. Tagore rejected progress understood as accumulating material riches. Like Gandhiji, he advocated an ethic of trusteeship: protecting nature’s resources for future generations and putting people, particularly the deprived, at the centre of decisions for change. For this, Gurudev advocated an approach to education that “makes our life in sympathy with all existence”. Visva-Bharati, Sriniketan and Shilpa Sadan were expressions of this dream. Its endurance now requires testing relevance in such changed circumstances. Contact with the earth, the element that brought Tagore to Santiniketan is now being lost as the countryside decays and migration thrusts millions into urban slums in search of survival. Village communities have local as well as urban ambitions, fueled by competing lifestyles. Today’s crafts emerge from urban slums as much as they do from rural cottages. Hazardous notions of progress are imbedded elsewhere as well. One example emerged in the midst of CCI partnership with Economic Census authorities. An unusual directive emerged from the Ministry mandated to protect Indian craft. An electric motor was recommended for handlooms. The stated objective was to improve ‘productivity’ and ‘incomes’ for languishing weavers, through handlooms converted into ‘modern’ power-looms. At one stroke, an astonishing Indian advantage with global demand would be destroyed. Weavers were not fooled by crocodile tears, or by the powerful pro-mechanization lobbies operating from the wings. Throughout the country, weavers rose in revolt. Possibly because a national election was around the corner, this idiotic scheme was dropped. Yet the threat remains, reappearing with regularity and most recently with recommendations that jacquard looms should be motorized for ‘productivity’. Secure livelihoods give real meaning to sustainability, as well as to those other qualities that make craft so unique as a development force. Responding to craft threat with craft opportunity demands thorough comprehension of the values upon which Gurudev’s efforts were founded. He wanted “to bring life in its completeness into villages”. How can that mission be sustained within rapid urbanization and new aspirations? How can Tagore’s ideal of education as ‘learning by doing’ be taken not just to villages but also to towns and cities? Can handcraft become an engine for self-reliance, with creativity and aesthetics making artisans job creators rather than job seekers? While Gurudev spoke more eloquently on aesthetics, Gandhiji too regarded creation as an art. For both, craft as art had to have profit-yielding livelihood at its base. Tagore wanted handmade products to have economic value “at home and commanding a ready sale outside”, embracing utility with creativity and drawing for inspiration on universal sources. These early directions need to be remembered because all these years later, limited marketing capacities challenge every craft opportunity. Hand production must be founded on management capacities that can deliver sustainable livelihoods within conditions of constant change and accelerating competition. Yet after a century, the absence of professional marketing systems remains the greatest of all challenges for the future of Indian craft. As early as 1924 Sriniketan was conducting market studies, and by 1937 Netaji had inaugurated a Sriniketan emporium in Calcutta. Aware of competition and change, Tagore and Gandhi understood the need to both respond to demand as well as to create and mould it. Where ‘the future is handmade’ At the time CCI and its partners were subjected to that ‘sunset’ shock, a pleasant surprise emerged from within the European Union. From there, a new slogan had been coined: “The future is handmade”. On enquiry, it was explained that survival in today’s competitive markets requires creativity and innovation. These resources and capacities are rooted in traditions of craftsmanship, as demonstrated by Japan and the Asian Tigers. Unless revived, the loss of Europe’s handicraft traditions could mean sacrificing tomorrow’s markets. Another welcome shock was delivered at the World Crafts Council 2014 assembly, held in China. Delegates heard that a decade earlier China had identified two “sunrise industries” as essential to its ambitions of economic power: IT and crafts! The contrast with India, the largest craft resource in the world, could not have been more striking. A transformational agenda Another opportunity for positioning craft industries has come in 2016 with the ratification by UN members of its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Several of its 17 goals --- integrating economic, social, environmental and rights issues --- offers an agenda close to Gurudev’s acknowledgment of crafts as an opportunity for “life in sympathy and harmony with all existence”. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) thus recall the holistic understanding of human wellbeing that impelled his efforts at Santiniketan. They reflect a growing consensus on progress and modernity understood as decent lives lived out in conditions of equity and justice: “where the mind is without fear and the head is held high”. SDGs offer relevance as well as urgency to the vision that created Tagore’s institutions. The message from Santiniketan seems to be that, away from glitzy images of Singapore and Silicon Valley, tomorrow’s dreams could be transformational if key issues are addressed with Gurudev’s wisdom and courage:

- What is the modernity India should seek in this new millennium?

- What actions can restore crafts as central to Indian wellbeing?

- Can crafts have relevance outside village societies and economies? Can Gurudev’s objectives be brought to crowded urban communities?

- How can education help foster a value for crafts within today’s attitudes, aspirations and priorities?

- What can be done do to provide dignity and respect for artisans and for their wisdom, and for building their capacities as job-makers?

- What collaborations can help move artisans from ‘sunset’ to ‘sunrise’, toward a future that is ‘handmade in India’ and of service to the world?